Every time I go to Mexico City, I come with a checklist of things I still have yet to see and do. And no matter how many items I tick off the list, I always come home with a new list twice as long. Every time I meet someone new, a seasoned local, we always get to chatting and they tell me about new, more incredible places I just have to see. This Spring, I finally made it out to see the great UNAM campus. UNAM has been on my list forever. And yet every time I somehow managed to miss it. But this time I made a point to not let that happen. And I was thrilled to walk out onto the quad and see all the outstanding architecture that surrounds it.

About UNAM

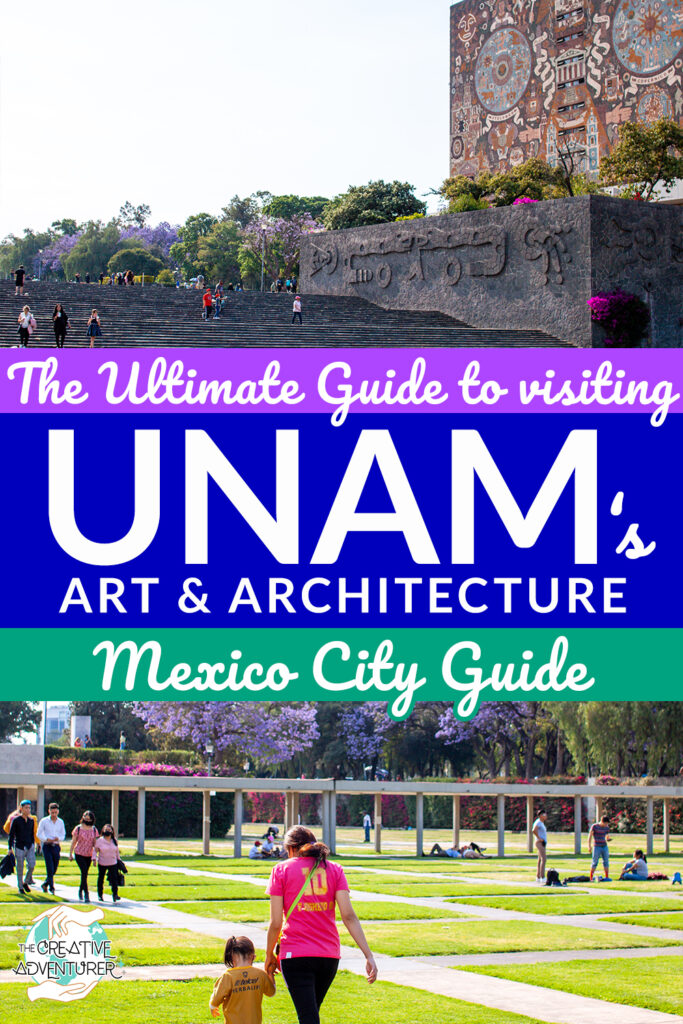

UNAM stands for Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and is the largest university in Latin America and has one of the biggest campuses in the world! The mesmerizing central library is the highlight of the campus, designed by the illustrious architect and painter Juan O’Gorman. The library’s mural is designed like a codex, filled with symbolic imagery to decipher. I could have sat there for hours just looking at it. But it is not the only building embedded in hidden symbols and rich history. There is so much to see here that lends itself to a better understanding of this amazing city.

But happenstance, we arrived on graduation day. The ceremony had just finished, but many graduates were still milling around in their gowns on. Taking pictures, hugging their family and friends, smiles brimming across their faces. Lots of them were camped out on the lawn having a snack in the sunshine taking in this important moment. It was such a joyful time to visit and definitely worth the drive!

About this Guided Tour

While walking around the campus, there isn’t much informational signage for tourists, it’s a working campus, after all. So I wanted to create this guide to help visitors and guests contextually explore this fantastic architectural wonder and mini-city. The entire campus is a tremendous example of Mexican Modernist architecture, which defined the landscape 70 years ago. So much so that the entire place was honoured as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007. But being able to have a better understanding of who made the buildings and why will really improve your experience of touring the UNAM campus!

- About this Guided Tour

- Access

- History

- Architecture

- Estadio Olímpico Universitario

- Campus Balcony

- Rectory Tower

- The People to the University, the University to the People

- New Symbol of the University

- Dates of the History of Mexico

- Central Library

- North Wall | The Pre-Hispanic Past

- Tlaloc

- South Wall | The Colonial Past

- Tlaloc Fountain

- East Wall Mural | The Contemporary World

- Viva la Revolution

- West Mural | UNAM and Mexico Today

- The Faculty of Architecture Building

- The Conquest of Energy Mural

- The Return of Quetzalcóatl

- Quetzalcóatl

- Chemistry Building Mural

- Cosmic Ray Pavilion

- Faculty of Medicine Mural

- Overcoming of Man through Culture

- Visiting the South Campus

Access

The UNAM Ciudad Universitaria (University City) is located in the southern part of Coyoacán. Visiting the campus is a great thing to do either in tandem with a visit to Coyoacán or San Angel.

Where & When to Arrive

Although the campus is located in the neighbourhood of Coyoacán, it is pretty tough to walk to from central Coyoacán. The best way to get there is via Uber. The entire campus sprawls over 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres), but the most important architectural structures can be found in the northern section. There are several parking lots around the library that can be used for drop-off and pick-up locations.

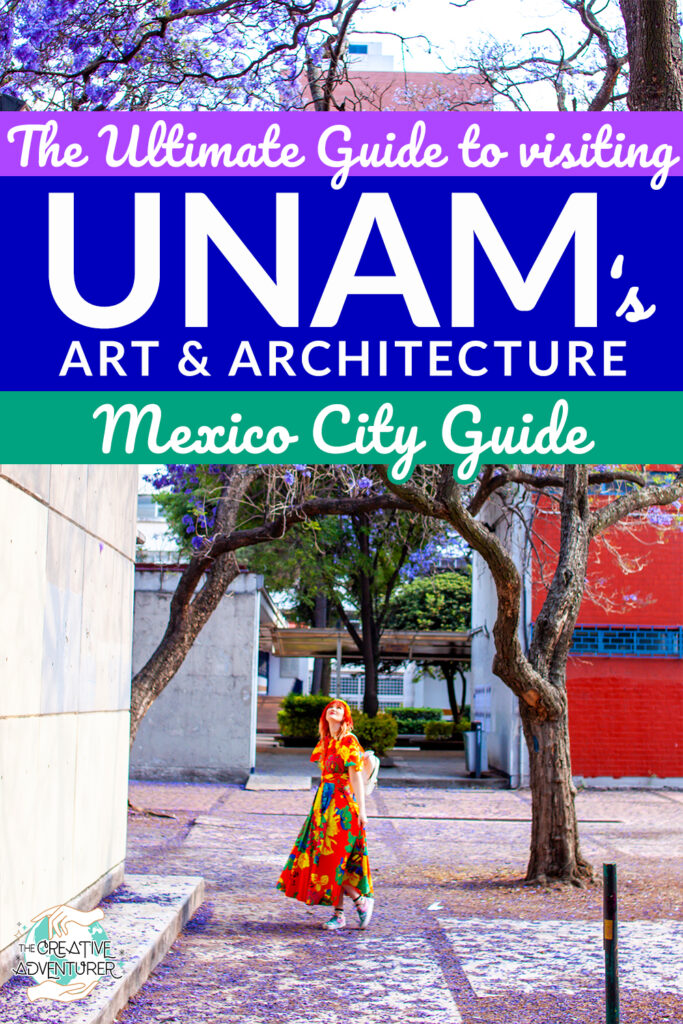

The best time to visit the campus is on weekends, particularly Sundays. This way, you’re not getting in the way of students and teachers on their way to classes. On the weekend, the wide-open green spaces of the campus are popular with families and students. They come here to relax, enjoying the patios, gardens and footpaths. During the springtime, the Jacaranda trees here are absolutely spectacular! So if you’re visiting the city during their blooms this is one of the biggest hidden gem places to see them.

Access around the Campus

UNAM has the word “autonomous” in the title because the campus itself truly is almost like its own little city. They have their own private security and police, fire department. And even their own public transport. The Pumabús run around the campus and to the main metro stations. The buses are free and generally run pretty frequently during the week. If you’re trying to reach the further afield parts of the campus, this can be great to hop on. You can check out the various routes here.

History

The history of the university dates all the way back to 1520. When the Spanish invaded ancient Tenochtitlan, one of the first things the king of Spain established was a university. But from 1533 to 1867, this university was controlled by the Roman Catholic church. So despite its modern educational resources, the curriculum was greatly influenced by religious orders. Because of this, many students felt they were being impeded from studying modern philosophical and scientific developments that were happening around the rest of the world.

In 1810, the last controlling Spanish forces were defeated by the Mexican insurgent army. The country was free and a new wave of revolution spread across the country. In 1867, the old Spanish University was closed by the government of Benito Juarez. After its closure, several independent schools opened up to teach everything from law, medicine, engineering, and architecture.

The Creation of UNAM

In 1910, President Porfirio Díaz saw the potential of these various disparate organizations. He organized to join them together to form the new National University, the new UNAM. The university’s aim was to develop a new Mexican identity and create a new model to drive the country into the future.

Tlatelolco Protest

Sadly, the very revolution that was meant to free the students from the control of the Spanish educators would only lead to a new form of control. In the 1920s, all Mexican universities were placed under government control. This went on to include UNAM in 1929. Over the years, this led to much internal turmoil leading up to the historic Tlatelolco protests in 1968. Only days before the 1968 Olympics, a student demonstration that opposed governmental interference in education ended in the massacre of hundreds of peaceful students. Protests still occur today as the students and teachers are constantly attempting to ensure education is free and separate from governmental control.

Architecture

The design of the current incarnation of the UNAM central campus was the idea of two former students. In 1928, Mauricio De Maria y Campos and Marcial Gutiérrez Camarena started to develop the plans for this new campus city. But the sheer size and scale meant that they needed much more assistance. Over 60 different architects were employed to achieve their vision. A beautiful example of Mexican artistic collaboration. The campus was to include the giant Estadio Olímpico Universitario, 40 other school buildings, and a massive library. It also had a cultural centre, several museums and a sculpture garden inside the ecological reserve.

Construction began in 1950 outside of the Pedregal de San Ángel. The area upon which UNMA university was built is atop an ancient solidified lava bed. The volcanic bedrock was removed when construction began. But never one to simply wash away the natural history of the country, the architects repurposed these uncovered rocks. They used them to make the pathways and embed into the walls of the surrounding structures. The area was also a historic place for an ancient Aztec civilization. University Rector Luis Garrido said, “it was once the seat of an ancient civilization, and now it will be the seat of the culture of the future.”

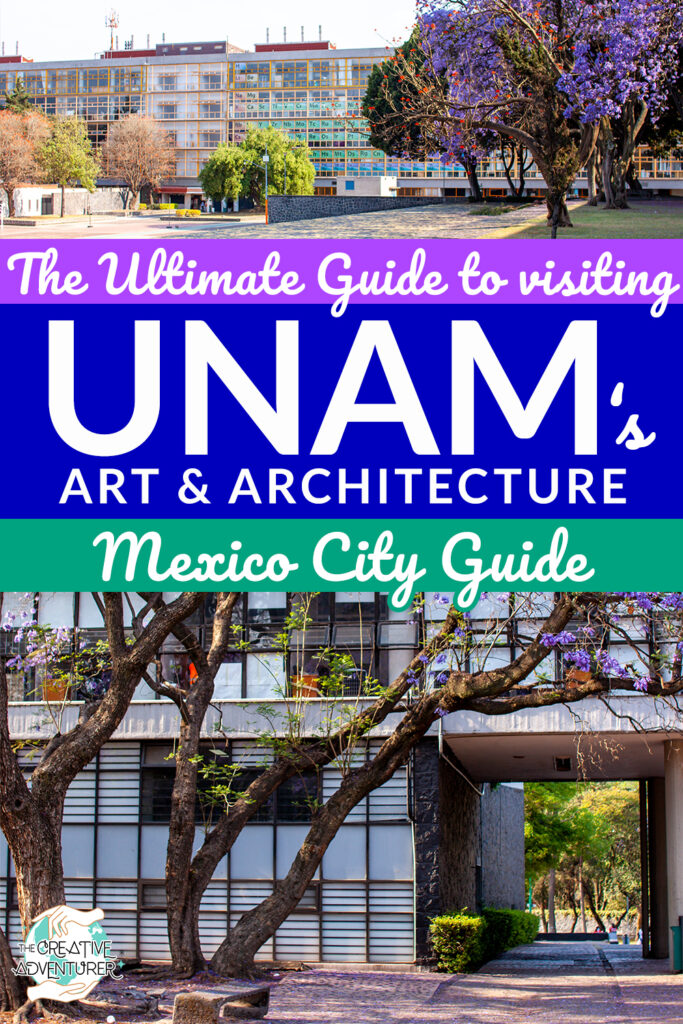

Mexican Modernism and Functionalism

During the university’s construction, the architects were highly influenced by the functionalism style. The concept of functionalism was that everything in society should serve a function. In architecture, it’s the principle that buildings should be designed based solely on their purpose and function. This style was popularized by ‘Le Corbusier,’ a home designed by German architect Mies van der Rohe. Mies van der Rohe wanted to radically simplify constructions to highlight their architectural beauty and focus on their function.

The other style highlighted here on campus is Mexican Modernism. Like functionalism, Modernism did away with ornaments and decorations in favour of innovation and new materials. Newly introduced to Mexico, concrete was used throughout the campus, along with lots of glass and steel.

In Modernism, many buildings have a long and low horizontal base juxtaposed at 90 degrees with a vertical tower. This emphasis on horizontal and vertical lines and asymmetry creates a visual effect of expanding the perspective.

Estadio Olímpico Universitario

The best place to start your UNAM campus tour is actually on the other side of the main campus. Outside the grandiose Estadio Olímpico Universitario or the University Olympic Stadium. The stadium was built in 1952, and at the time, it was the largest stadium in Mexico. It was built in anticipation of the 1968 Olympics, the first Olympics in Latin America. During the Olympics, the stadium would host track and field competitions, equestrian events, football matches, and, most importantly, the opening and closing ceremonies. So the architects really wanted to leave a lasting impression on the world.

During the Olympics, it was here that the iconic image of Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the podium was taken. They each raised their black-gloved fists in the air, in solidarity with the Black Panthers. This symbol was an act of protest against the rampant racism in the US. Fittingly this protest was held on UNAM soil, a university so well familiar with protest. Today, the University uses the stadium for their football games with their home team, the Pumas!

Diego Rivera Mural

Outside of the main entrance, on the east side of Avenue de Los Insurgentes Sur, stands the powerful relief made by Diego Rivera. Diego Rivera was perhaps the most significant artist involved in the government-sponsored Mexican Muralism project. He is considered one of the “big three” artists, the others being David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco. In 1920 the government hired these three artists (and others) to help educate the masses about Mexican history. Their aim was to use art to reunify the country. Back then, much of the population was illiterate and therefore these pictorial images were the perfect solution to reach everyone. As the movement continued, the art shifted from representations of the past to dreams for the future.

For this project, Rivera used only natural stones to create the mural. He sourced them from around the area to make the relief feel like an ancient structure that had been uncovered. Unfortunately, Diego Rivera died before the installation could be finished. He had initially planned to cover the entire building in these stone mosaics. But after his death, the work was never completed.

The University, the Mexican family, peace and youth sports

The mural’s name is quite the mouthful, being called the “The University, the Mexican family, peace and youth sports.” The centre of the relief features a mother and father with their arms outstretched. Their hands reach toward their child, who stands in the centre. The child clasps a large dove in his hands, the symbol of peace. Behind the family, wrapping their wings around them, are a mammoth golden eagle and fierce condor. These birds are the symbols of UNAM University.

On either side of the family, there are two athletes seen in white sports uniforms. They are in the process of lighting the ceremonial Olympic flame. Below all the characters in the scene, we can see the image of the pre-Hispanic god Quetzalcoatl. Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, acts as the ground upon which these athletes stand. The scales of his skin are decorated with images of corn, an essential resource which forms the fabric of Mexico’s agriculture.

Campus Balcony

To head into the main campus area, you can cross over the pedestrian bridge, travelling over the highway. The pedestrian crossing is located slightly north of the entrance to the stadium. After crossing, you’ll see the grassy Edén Garden. This small green space is a frequent hangout for students who want to snag some shade under the trees. Walk slightly south, parallel to Escolar street. Eventually, you will pop out next to the ‘Rectoría’ bus stop.

This large concrete quad sits above the rest of the campus. The raised dais gives you a beautiful view across the campus. The quad was planned out with wide steps leading down to the rest of the campus. This design was inspired by ancient Aztec cities, which resembled large outdoor rooms. The open courtyard and terraces of ancient cities like Teotihuacán, Monte Alban and Chichen Itza were all used as inspiration for this layout.

Concrete was new material in Mexico City during the university’s construction. After the revolutionary wars in Mexico, much rebuilding needed to be done. And concrete allowed many buildings to go up quickly and relatively cheaply. The main focus of this reconstruction was directed toward healthcare, education and public works.

Rectory Tower

Walk towards the southeast corner of the balcony and down the stairs. In front of your stands the imposing Rectory Tower to your right. The tower is an exemplary model of modernist architecture. The juxtaposition of a wide horizontal lower level with a large vertical tower creates the effect of elongating the buildings. Walk down the stairs to your right to make your way around the building.

As you descend, take a moment to study the beautiful natural colours of the building. The dividing walls which separate the rest of the courtyard from the Rectory Tower are made of black volcanic stones. The walls of the main horizontal building are covered in tiles made from brilliant yellow onyx. Yellow onyx is a semi-transparent stone that allows light to reflect off of it while also illuminating the building with gorgeous, diffused natural light.

As you make your way to the bottom of the stairs, you can see the charming black and white checkered pattern made of different blocks that forms the lower level. Walk up close, and you can see the small voids in the blocks that also provide natural lighting to the building.

The People to the University, the University to the People

On the south side of the building, you’ll find the vibrant, three-dimensional “sculpture-painting” by Mexican Muralist David Alfaro Siquieros. The Rectory Tower actually features three murals by Siqueiros made starting in 1952. Unlike other two-dimensional murals, Siquieros was employing a new technique he was developing of three-dimensional painting. He used the new material of cement to layer upon the painting to bring the mural to life. The cement was then covered with thousands and thousands of brightly coloured glass mosaics.

The mural on the south side is titled, “The people to the University, the University to the people.” It features sculptures of five different university students in warped and elongated positions. In their hands, they are holding various objects representing the knowledge they acquired at school. In the background are images of the modern city into which these students are headed after graduation. A city where they can apply their knowledge and be the change they want to see in the world.

New Symbol of the University

Turning around the corner, on the east side, you can see a large balcony-like projection coming out the side of the building. This mural is called the “New Symbol of the University” and features the images of two large slightly abstracted images of birds. As we saw in the Olympic Stadium, these are the birds of the University and represent the golden eagle and great condor. The golden eagle has long been a symbol for Mexico City. The two birds are situated on either side of a brilliant sun, symbolizing truth and knowledge. See how the wings of the birds wrap around the edges of the walls continuing into the building.

Dates of the History of Mexico

Coming back around to the front of the Rectory Tower, you can study the last of the three Siquieros murals. This one is called the “Dates of the History of Mexico.” Above the entrance to the building is a large painting of a series of hands. One hand bursts forth from the frame, becoming sculptural, holding a pencil almost like a sword. The reverberations though that seem to echo out from the hand almost look like the sound waves made by a firing bullet. In this place, it’s knowledge that is the strongest weapon!

On the left side of the mural are a series of dates. Each one refers to a significant moment in the history of Mexico City. 1520 was when Mexico was first invaded by the Spanish. 1810 was the Mexican War of Independence when Mexico was freed by insurgent forces from the Spanish. 1857 was the Reform War and the formation of the Federal Mexican Constitution. 1910 was the second Mexican Revolution against the government of President Porfirio Díaz. Finally, we see the date 19?? signifying that Siquieros thought that there would still yet become a monumental moment in the 20th century for the country. Many students etched the date of the protests onto the mural but this has been removed year after year.

Central Library

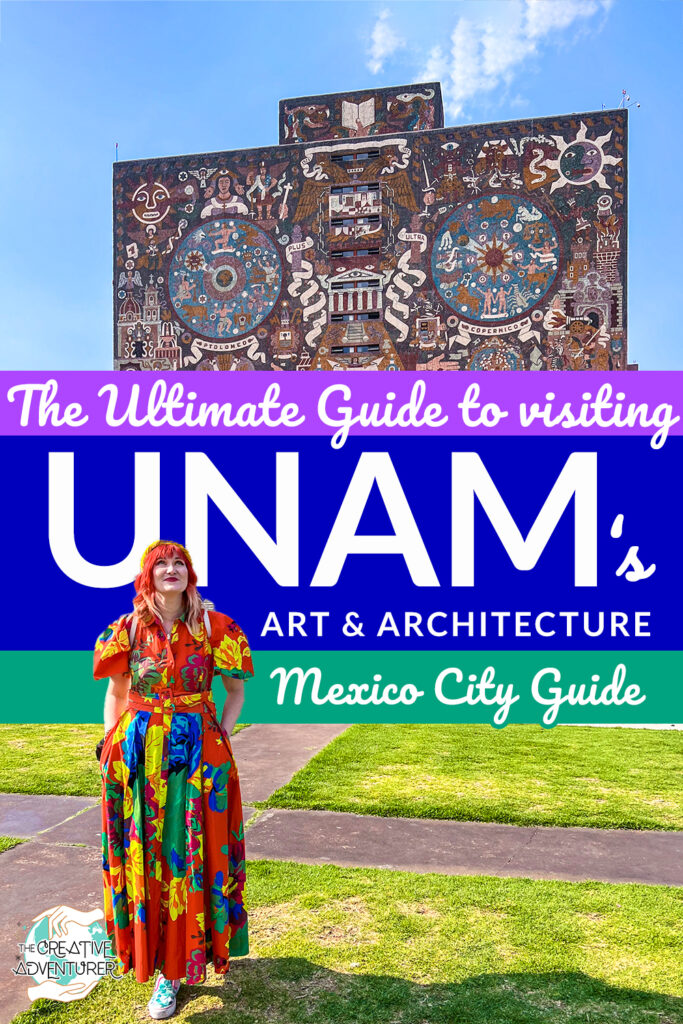

The Central Library was definitely the main reason why I made my way out here. And it is without a doubt the most symbolically important building on campus. The Central UNAM Library contains one of the largest book collections in Mexico, with over 600,000 books tucked away inside. To ensure all these books were safe from the destructive rays of the sun, the library needed to be primary windowless. But a windowless building can look pretty boring. So the architects knew the building needed something eye-catching to decorate the facade. They hired painter and architect Juan O’Gorman to create a fantastical, almost storybook-like mural that wrapped around the entirety of the library.

Juan O’Gorman Vision

Juan O’Gorman was born just a few steps away from the university campus in Coyoacan. This was his home turf and as such he really wanted to create something special. O’Gorman employed the use of the black volcanic stones, hewn from the ground, to become the base of the facade. Unlike the other murals on campus, O’Gorman wanted the colours in his mural to be completely natural. No paints or pigments, all the colours in the mural were made from finding organic materials. Stones from all over the country were sourced to create the coloured tile on the facade.

O’Gorman’s idea was to use the facade of the library to paint a picture of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic culture and identity. As well as the future he saw for his country. The entire mural is assembled like a codex, with hidden symbols to be read around every corner. The North Wall represents the pre-Hispanic past, and the South Wall depicts Colonial Past. Then we move to the East Wall, which represents the Contemporaneous World. And finally, the West Wall depicts the University and Modern Mexico.

“The general theme of the mural is related to the evolution of culture. In the upper part, I represented the cosmological symbols, on the north wall, figures allusive to the pre-Hispanic culture, on the south wall, I developed the argument about colonial culture, on the sides, I referred to the modern age, and on the east side, I represented the atom as a cosmological symbol of our century. I had originally projected the Newtonian concept of universal attraction on the west side. I had to vary it by having to represent there the university shield with the corresponding motto, which, in my opinion, should have gone in the rectory building.”

– O’Gorman

North Wall | The Pre-Hispanic Past

To read the building chronologically, head to the north side. This is where we can look up to view the wall dedicated to the pre-Hispanic past. Flowing throughout the entire mural are bright blue watery canal and earthy “chinampas.” These chinampas, or artificial islands, were a brilliant invention by the Aztec civilization. These floating gardens provided the nation with rich agriculture and even a modern drainage system. Water was life to the early Mexican people, and as such, the water in this mural acts almost as veins. Connecting each section to one and other.

The Duality of Life and Death

The overall theme in this mural relates to the story of life and death. In the Aztec civilization, life was represented by the sun and death by the moon. These two dualities needed to exist in tandem to create that important harmony which balances life on earth. One needs the other to exist. Without death, there is no life and vice versa. So unlike today, where death is something to fear, something we shy away even from talking about. The Aztecs revered death and honoured it for its place in the cycle of life

Quetzalcóatl

Let’s start the reading of the mural on the left side. Here we see a small scene dedicated to life-giving Aztec gods. In the upper corner, we can see the sun’s image, set within a geometric set of Aztec designs. Driectly below the sun we can see the tail of a large snake. As we follow its slithering body we find its head facing the centre of the frame. This snake represents the Aztec god Quetzalcóatl. Quetzalcóatl, or ‘the Plumed Serpent‘, was one of the most important gods in ancient Mesoamerica. He was thought to be a mix of a bird and rattlesnake. If you look closely, you’ll see multicoloured feathers combined with his emerald scales.

Quetzalcóatl was the god of the wind and the rain. And it was Quetzalcóatl who was said to have created the earth and the people who live upon it. The brightly coloured feathered headdress worn by the priests of ancient Mesoamerica were meant to mimic the image of Quetzalcóatl. Many of the people in the mural can be seen wearing these elaborate headdresses. From below the centre of the snake, an amputated hand emerges from the stone. From their fingertips, droplets of water pour down on the large tree below. Perhaps the human form of Quetzalcóatl watering the resources on earth.

Huitzilopochtli

To the right of Quetzalcóatl’s hand, we find the image of the god Huitzilopochtli. Huitzilopochtli is the Aztec God of the Sun and War. He is wearing a feathered hummingbird headdress, holding a large shield with the star. In his other hand, he holds a curved turquoise staff and is surrounded by a series of fearsome snakes. In the Aztec culture, warriors were reincarnated as hummingbirds after their death in honour of this fearsome god.

The Myth of the Sun and Moon

Huitzilopochtli was conceived when his mother, Coatlicue, saw a ball of hummingbird feathers falling from the sky. Similar to the immaculate conception of the Virgin Mary, upon collecting the feathers, Coatlicue became with child. But just before he was born, Coatlicue’s sons and daughter devised a plan to kill both the unborn child and their mother. They were blind with jealousy at the extraordinary way he was conceived.

But just before they could enact their plan, Huitzilopochtli burst forth from his mother’s womb. Born armed with the turquoise snake staff and full armour, he fought off his siblings to protect his mother. He threw his sister off the mountain, and she became the moon. Huitzilopochtli then chased his brothers, who ran away into the sky, becoming the stars. Huitzilopochtli, who was born in anger and fury, became the sun. And it is said that the reason we have day and night becomes Huitzilopochtli continues to chase his brothers the stars around the world every day.

Tlaloc

Below the disembodied hand, beside the tree being watered, we can see the Tlaloc, the Aztec god of rain. Tlaloc also goes by the name ‘He Who Makes Things Sprout‘ so it is apt to see him in the process of raising a tree from the earth. He is very recognizable by the large mask he wears with these two huge eyes and a large set of white fangs. As the god of the rain, Tlaloc was the ‘giver of life’ responsible for earthly fertility. While Tlaloc was seen as, on the one hand, the giver of life, he was also greatly feared. Again, going back to the harmony that must exist in all things. Tlaloc was also responsible for hurricanes, lightning and floods. He could grow and destroy crops all in one breath.

Tlazōlteōtl

In the center of the left section, we can see the image of a woman covered in flowing strips of fabric. This is Tlazōlteōtl, my persona favourite of all the Aztec gods. Her name “Tlazōlteōtl” is the Nahuatl word for garbage. And often she is called the “Eater of Filth.” And while that seems rather derogatory, she is one of the most precious of all the gods. Tlazōlteōtl has many names, sometimes called the Eater of Excrement. This “excrement” that she eats is representative of the sins of the world. Giving those who pray for her absolution and perhaps a new lease on life. She is often identifiable by the rim of black around her lips from the eating of dirt.

Tlazōlteōtl is almost always portrayed in a splayed leg position, as if in the process of giving birth. Another one of her names is Goddess of the Moon as the moon is a symbol of fertility. Tlazōlteōtl is often portrayed alongside the jaguar who is associated with water, plants and fertility.

Another one of her names is Goddess of Cotton. In the Aztec culture, weaving and fertility go hand in hand. Women were both the ones to give birth and the weavers of the household. Textiles brought lots of money into the household. And a highly skilled weaver was considered a highly prestigious position. That is also why Tlazōlteōtl is often seen adorned in fabric.

Teccistecatl

To the left of Tlazōlteōtl, we can see the top of a great pyramid decorated in images of shells. Atop the pyramid’s terrace sits the god Teccistecatl on his throne. Teccistecatl is the male version of Tlazōlteōtl. He is the male god of the moon and fertility. His name means, “Place of the Conch,” and he can be seen blowing into a large conch. Teccistacatl is often seen wearing a white seashell on his back, a symbol of the moon.

The upper portion of the mural has all related to the world of the gods, but the pyramid guides us into the earthly plane. The various Aztec warriors can be seen wearing animal pelts on their backs. They were given his costumes featuring eagles, jaguars and snakes as a means to imbue themselves with the powers of those animals. A priest wearing a feathered headdress stands surrounded by the warriors in the midst of a ritual. O’GormanO’Gorman believed that the Mexican empire was built on the backs of their fierce warriors and the rituals of war.

Tonatiuh

The central axis of the mural is dominated by the god Tonatiuh. Tonatiuh is the god of the daytime sky and controls the sun’s movements. Tonatiuh takes the form of the sun. He looks out almost menacingly at the people below with his red tongue emerging from his mouth. Tonatiuh is one of the oldest Aztec gods. They believed that his movements caused the sun to rise and set in the evening. But this life cycle was only guaranteed by the human sacrifices on earth.

Tōnalpōhualli

Below Tonatiuh we can see a pink mouth with teeth bared, surrounded by an ellipse. The ellipse is divided down the centre, with one half being black and the other white. In the centre of the ellipsis, you’ll see twenty different symbols representing the different 20 13-day periods of the Aztec solar calendar. This calendar was called the Tōnalpōhualli, which in Nahuatl means “count of days,” invented around the 1st millennium BCE. Each symbol is a powerful element in Aztec life. They were everything from deer, water, skulls, earthquakes, flint and wind. Each day is governed by a different deity.

The Eagle of Mexico

Below the Tōnalpōhualli, we can see the great symbol of Mexico City. Or as it was known then as the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan. The national emblem is the image of an eagle holding a snake in its beak atop a cactus. The Aztecs were told to search the entire country until they saw this image. When they spotted it, it was there where they were to build their capital city.

The Moon Rabbit

In the top right of the frame, we can see the image of the full moon, in contrast to the sun we saw on the left. Inside the moon look carefully to see the small red rabbit. The rabbit is closely associated with the moon in Aztec history. The legend goes that when Quetzalcoatl came to earth as a human, he started on a long journey through the woods.

Quetzalcoatl quickly became exhausted in his new human form. Quetzalcoatl thought he would die alone in the woods without food or water. But then he saw a rabbit grazing nearby who offered to share his food with Quetzalcoatl. After regaining his strength, Quetzalcoatl took the rabbit and lifted it to the sky. He pressed it against the moon. When he brought it back down to earth, he said, “You may be just a rabbit, but everyone will remember you; there is your image in light, for all people and times.” Perhaps because of the connection between the rabbit and Quetzalcoatl, we once more see the feathered serpent emerging from this side of the frame.

Tezcatlipoca

To the left, you can see the god Tezcatlipoca. Tezcatlipoca is the god of the night sky and Huitzilopochtli’s oppositional rival. The god of the sun and moon is seen positioned directly across from each other one the mural. You’ll notice more of these contrasting characters as we go. As Tezcatlipoca is the night god, he is seen with his familiar, the night jaguar. He is often accompanied by the image of a skull that can be seen to the right. Tezcatlipoca can be identified by the large obsidian shield he carries. Another identifying feature is the black (sometimes yellow) stripes painted across his face.

Tezcatlipoca often goes by the name “Smoking Mirror” as he is also the god of obsidian, divination, and sorcery. Obsidian was frequently used in important shamanic rituals. Look closely at the left foot he has pointed outwards. This foot is made of a large bone after Tezcatlipoca’s battle with a mythological Earth Monster.

Chalchiuhtlicue

Moving slightly to the right, we can see the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue. Chalchiuhtlicue is the goddess of water, the partner (or sometimes sister) of Tlaloc. She is easily identifiable by the flowing jade skirt she wears. The skirt is meant to resemble the flow of a stream of water erupting behind her.

Directly in front of her, you can make out the image of a great bonfire, with a green shape within. Look closely and you’ll see human-like eyes staring out from the fire. Chalchiuhtlicue is throwing her son into the fire. Sacrificing him to give life to the moon. The Aztec festival of Chalchiuhtlicue involved human sacrifice and often involved women and even children.

Mictlantecuhtli

In the right middle section, we see the image of two gods back to back, standing above what appears to be a minature pyramid. Perhaps the pyramid is actually meant to be human-sized and the gods are depicted in their true form, showing the viewer their sheer enormity. The two gods are Mictlantecuhtli (on the left) and Quetzalcóatl (on the right). Mictlantecuhtli is the god of death and the lord of the Underworld. As seen by the staff he carries with a huge skull embedded in the centre. Quetzalcoatl on the other hand is the god of life, knowledge and light. Together they symbolize the theme of life and death.

The legend of Quetzalcoatl & Mictlantecuhtli

One of the legends surrounding these gods related to the creation of life on earth. One day, Quetzalcoatl went down into the underworld in an attempt to steal the bones of the previous generation of gods. But Mictlantecuhtli didn’t want to give them up. So Quetzalcoatl had to sneak in, but he was caught and dropped the bones in his attempt to quickly escape. The bones were broken during the fall, but Quetzalcoatl quickly grabbed as many as possible and returned to the surface. Upon returning to the surface, the bones were transformed into the different races of mortals on earth. Each one has a different shape and size due to the bones being broken into different pieces after the fall.

The Sacrifice

The lower section of the right murals is dedicated to the warrior’s sacrifice. Every Aztec warrior was required to provide at least one prisoner of war to be sacrificed. Only a warrior who had captured an enemy and offered him up to the gods was able to call himself a true warrior. The warriors can be seen wearing feathered headdresses to look like the gods they so revered.

South Wall | The Colonial Past

Moving now to the south wall, this is the wall you see most prominently when you walk into the courtyard. This wall moves away from Aztec mythology and into the colonial past. And yet even as the city is being torn apart by the colonizers, the veins of Aztec beliefs still run throughout. The south wall studies the dichotomy between good and evil, represented here on the left and the right by religion and violent war. But in reality, these wars were truly a war on religion itself and tearing away the deeply rooted beliefs of the Aztec culture. And imposing on the indigenous people the new world of Christianity.

Spiritual Conquest

The mural’s left side is themed around the history of the religious conquest that occurred when the Spanish invaded Tenotichilan. On the top left, we can see a large image of the sun. Its rays cast light upon the figure of a man to the right. The man wears on his chest a large golden cross. On either side of his shoulders are two disembodied hands that appear out of a triangle with the all-seeing eye within it. On either of the hand’s palms, we can see two red dots representing the crucifixion wounds of Jesus Christ. In the background of the mural, surrounding the large blue circle in the centre, are various images of angels and religious iconography. This includes repetitive images of the golden cross and sceptre.

The Eye of Providence

The eye enclosed in a triangle surrounded by rays of light is called the ‘Eye of Providence‘ or the all-seeing eye of God. It is the divine image of God who watches over humanity. This eye is seen all over this side of the mural. This image is most often connected to the Freemasons, a religious order that dates back to the 13th century. The activity of the freemasons in Mexico has very deep and secretive mythology. But it is believed that many of the leaders of Mexico belonged to Freemasonry. Perhaps O’Gorman knew something the general public didn’t and this was his way of getting those secrets into the public eye.

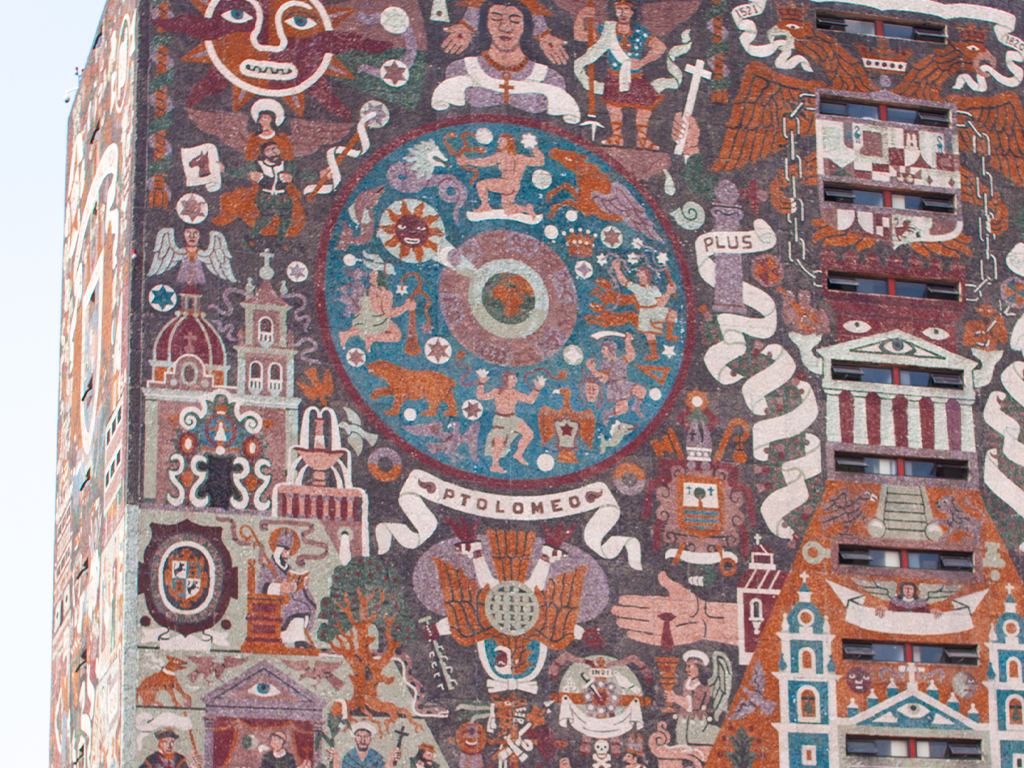

Claudius Ptolemy

Without a doubt, the most impactful part of this mural are the two huge blue circles on either side. They look out at the mural like a pair of giant eyes. Following you wherever you go. These represent two opposing views on astronomy. On the left, a small banner hangs below the circle with the name “Ptolomeo” written upon it. Ptolomeo or Claudius Ptolemy was a famed astronomer and astrologer who came to prominence in the Roman Empire. He wrote several important treatises. The most influential of which was his geocentric system. This paper stated the sun revolved around the earth.

The blue circle on the left is meant to reflect those ideologies. In the centre of the circle, we can see a small image of the earth and, around the circumference, the image of the sun revolving around it.

Constellations

In the middle of the blue circle, you can make out several small white stars in amongst a sea of larger symbolic images. Each one represents a different constellation. These are a select few of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Claudius Ptolemy in his 2nd-century astronomical treatise. Most of them are associated with stories from Greek mythology.

At the top, we can see Hydra, the multi-headed water snake slain by Hercules. Moving clockwise, we then see Pegasus, the winged horse who carries thunder and lightning to Zeus. The crown represents Corona Borealis, the crown worn by Princess Ariadne on her wedding day. Below the crown is Orion. Orion is the hunter and son of Poseidon, who is joined by his two dogs. Next is Perseus, who famously slew Medusa the Gorgon and holds her head in his hand. The eagle we see is Aquila, the bird of Zeus and the retriever of his thunderbolts. At the bottom of the circle is Andromeda. Andromeda is the daughter of Cassiopeia and was chained to a rock. We can see her in the mural still enchained to the stars. Ready to be eaten by the sea monster Cetus.

Beside Andromeda is Ursa Major, the great bear. But once, this creature was a beautiful woman named Callisto, the lover of Zeus. When Zeus’ wife Hera found out Callisto was pregnant, she was furious and transformed her into a bear. To the bear’s left is Capricornus, who has horns like a goat. They are surrounded by several other water-related constellations such as Aquarius, Pisces and Eridanus. The final constellation is Delphine, the dolphin messenger of Poseidon.

Falling Eagle Cuauhtémoc

Directly below the constellations and the banner is the image of an upside-down eagle. The falling eagle is the symbol of great Aztec leader Cuauhtémoc. The name Cuauhtemōc means “one who has descended like an eagle.” This is the fiercest pose for an eagle; when an eagle folds its wings and plummets down, it is about to strike its prey. And yet, despite his aggressive name, Cuauhtémoc took power after the death of emperor Moctezuma II in 1520. His ascension to the throne was during the start of the Spanish invasion and the epidemic of smallpox that killed so many of his people.

The Burning of Cuauhtémoc

Although he tried to fight off the Spanish, Cuauhtémoc was captured and surrendered to Hernán Cortés, leading to the death of his beloved empire. Cortés kept Cuauhtémoc alive in the hopes he would show Cortés where the riches of the empire could be found. Although they had found some gold, it was nothing like what Cortes had expected. He subjected poor Cuauhtémoc to torture over red-hot coals, but Cuauhtémoc never gave anything up. This scene is somewhat depicted here on the mural. His ‘chimalli‘ shield and a feathered headdress are all that are left on the burning stake. Cortés had Cuauhtémoc executed but, to this day, he is considered a martyr by the Mexican nation.

Diego de Landa Calderón

Also being burnt on the pire are the precious Mayan codices. Diego de Landa was the Spanish bishop sent by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese to Mexico. It was because of him that all the printed histories of the Aztec empire were lost. This devastated historians as their chance at deciphering Maya script or learning more about their civilization were lost to these fires. We can see Calderón standing to the right, overseeing the fires, dressed in Catholic finery. But interestingly enough, the staff he carries resembles the pope’s pastoral staff but features a large skull. Perhaps a commentary on the death of the Aztec empire at the hands of Calderón and the Catholic church.

Habsburgs Crest

The mural’s centre is dominated by the enormous coat of arms featuring two huge eagles. This is the coat of arms of the Habsburgs. This dynasty ruled over Spain for centuries. The Hapsburg emperors contributed much to the formation of the country of Mexico we know today. The Hapsburg coat of arms is formed from the double-headed eagle. The eagle has always been a sign of emperors, but the double-headed eagle could only be used as an imperial title. This could be used for a king who wasn’t voted in by the electors but blessed and crowned by the pope in Rome.

Plus Ultra

A large banner spins itself around the coat of arms with the dates 1521 and 1820. These dates represent the start of the Spanish conquest to Mexican Independence in 1820. Another banner swirls itself around the side with the words Plus ultra. Plus ultra is a Latin phrase and the national motto of Spain. The motto can be translated to “further beyond,” which refers to the idea of taking risks and striving for excellence to move a nation forward.

The Churches

Below the great coat of arms, we see a trifecta of three different buildings atop one another. As we move down the mural, the building transforms into different architectural styles indicating the change in eras. At the very top, we have a series of Roman columns. Below this, we can see the great Aztec pyramids and finally end in the huge baroque Catholic church. Hidden inside many different architectural aspects of the buildings are more masonic eyes. It is also within this part of the mural where the real “eyes” of the building (aka the windows) are placed.

The Devil

On the right side of the mural, we have the image of the moon located in the top right corner. Juxtaposing the images of the sun on the left side. To the left of the moon, we can see the fearsome image of the devil, mirroring the same placement of god. The devil is surrounded by a series of vicious animals and monstrous creatures. Whereas on the left side of the mural, the disembodied hands hold crosses, these hands hold swords and spears. This immediately indicates to us the fact that this portion of the mural is all about war.

Copernicus

Mirroring the image of the large blue circle from the left, we can see another similar image on this side of the mural. On the right we can see another small banner with “Copernicus” written on it. Nicolaus Copernicus was a Renaissance astronomer who discovered and wrote the heliocentric theory. This theory stated that the sun was at the centre of the universe. And that the earth revolved around the sun and not the other way around. This started a charge in the course of scientific history called the “Copernican Revolution.” This discovery was at odds with the Catholic church. So much so that they had Coperniscus’ books banned for over 200 years.

The Zodiac

In the centre of this blue circle, we can see the sun and the image of the earth revolving around the circumference. Surrounding the sun is another set of images; this time, instead of Greek constellations, we find images of the twelve different zodiac signs.

Map of Tenochtitlan

Below the large circle, we see a mosaic image of the map of ancient Tenochtitlan. The beautiful waterways that surround the city vibrantly contrast the terracotta reds of the city. It might seem odd to see a map on the side of the mural dedicated to “war,” but this map show the rich land upon which the city stands. The nation’s wealth was the reason it was so valued and seen as something the Spanish needed to conquer and claim.

Cortes’ War

To the left of the map, we start to see the graphic depictions of war. Armed men on horseback arrive and can be seen charging in. Horses had been extinct in Mexico for thousands of years, which gave the invading Spanish army an advantage. A huge cannon explodes, its fiery expulsion directed towards the city. The combinations of armour, cavalry and this advanced weaponry meant that the Aztecs stood no chance of being able to defend themselves.

On the bottom right of the mural, we can see Hernan Cortes himself. He is identifiable because he is on horseback, in heavy armour, and wearing a large helmet with colourful plumes. He rides just behind a series of men carrying the Spanish flag as it appeared in 1521. This flag contained two lions and two castles in opposite corners. The two castles represent Castile and León, and the two lions are their rulers.

Laws of the Indies

To the right of Cortes’ entry, we can see a man carrying a scroll sitting in a golden-looking chair. Kneeling in front of him is the defeated Aztec army. The scroll carries the words “Ley de Indies,” which was the Laws of the Indies. The Spanish crown issued this body of laws that were used to regulate the social, political, religious, and economic life in all regions conquered by the Spanish. It was these laws that would start the governmental control over Mexico. These laws were just the start of the colonial system that propelled Mexicans to fight for their independence.

Tlaloc Fountain

In front of the south side mural, to the right of the entrance to the library, is a large stone fountain with the image of Tlaloc. The Aztec rain god is fittingly being used here to bring water to the steps of the library.

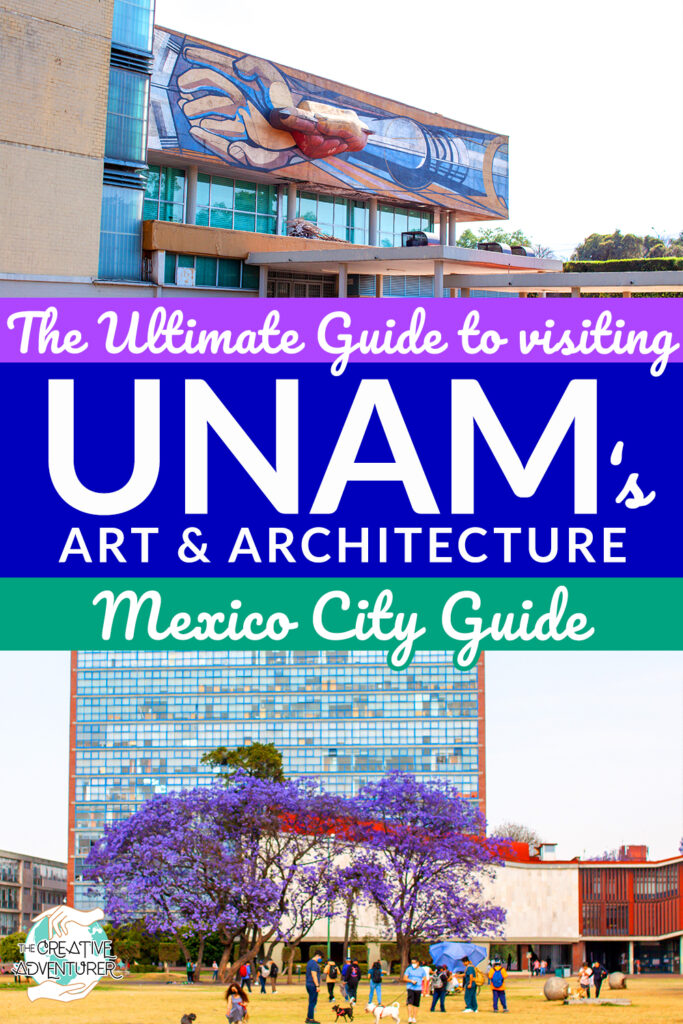

East Wall Mural | The Contemporary World

Along the east wall, which looks out over the large open-air grassy courtyard, we can clearly see the theme of the atomic age. The symbol of the atom in the centre of the mural represents the explosion of knowledge in the 20th century. Above the atom, we can see the great Eagle of Mexico rising up above. A symbol of the country’s spirit leading them into this new era of ascension.

The Sun and the Moon

And yet, despite the modernity that is featured on this side of the mural, on the top right and left, we still see the images of the sun and the moon. Both of which continues to be a through-line that connects all side of the library murals. The sun and the moon represent duality which we also see represented in the scenes of the city and country below.

The City’s Industry and the Rural Countryside

The left side of the frame represents the industrial progress of the nation, while the right side depicts the natural world. That natural world, Mexico’s rich agricultural landscape, remains unchanged, no matter the scientific progress around it. On the left we need a modern factory while the right we can see traditional Mexican architecture.

Below the image of the atom, in the centre of the mural, we can see a man dressed in Aztec garb. In one hand, he grasps a snake, while in the other, he holds a worker’s hammer. Above his head, on either side, respectively, are images of science and industry and the natural Mexican landscape.

Viva la Revolution

On the lower left of the mural, we see two men holding a banner proclaiming “Viva la Revolution!” They are the people who represent the people of the Mexican Revolution. Above them, the three men hold what appears to be a globe in their hands as if the introduction of the factories would lead to the creation of this new world.

Tierra y Libertad

On the lower right we see another group holding a banner stating, “Tierra y Libertad,” which translates into Land and Freedom. Unlike the factories, the people on the right represented farmers who work the land in the same way that has been down for many centuries, back to Aztec times. But just like the factory workers on the left, the also desire revolution and freedom for their country.

West Mural | UNAM and Mexico Today

The last of the murals we will look at is on the west side of the building. This side of the library faces the highway and acts almost like a billboard for cars passing by. The theme of this mural is all about the University itself. After all the previous murals, which reference the history of Mexico, we finally land on the present and the future of the country.

UNAM Crest

In the centre of the mural is the great crest of UNAM university. When O’Gorman created the mural, the crest had just been finalized, so this was a great way to announce it to the public. The crest of the University was designed by famed writer, philosopher, and politician José Vasconcelos. He held the position of university rector in 1920 when the seal was being redesigned. So Vasconcelos took it upon himself to bring his vision to life.

At the very top, we can see a banner flying in the wind with the words the National Autonomous University of Mexico in large letters. Below this is what appear to be two great golden eagles. But they actually are one Mexican eagle and one Andean condor. Each one facing out towards the university campus, as if on guard.

The two birds hold a great shield with a map in the centre front. This depicts a map of Latin America with a star where Mexico can be found. Around the shield is the phrase, “For my people, the spirit shall speak.” The motto speaks to the conviction of the Mexican people. Their ability to rise up against all odds, to protest,to fight, all the while their spirts enriched by their cultural history.

Below the shield, you can see the image of a volcano and a series of mountains, representing Mexico’s roots. Surrounding the great shield, O’Gorman wove a series of pre-Hispanic symbols and images to ensure that we always carry the past with us even as we move into the future.

Students of the Future

On the lower part of the mural, we see the images of the past and the present. On the left, we see the image of an old Aztec temple, contrasted on the right by the images of the modern architecture of the University. Below these structures are the people of Mexico City. On the left, we can see the indigenous Mexican wearing traditional dress, contrasted on the right by a series of students wearing the fashions of the 1950s. They are carrying objects relating to the various studies at the University like science, engineering, and sports.

Las Islas

From the library, take a stroll through the large grassy knoll called “Las Islas,” or the Islands. This large expanse of grass is almost always covered by students relaxing or studying in the sunshine. You can find street food vendors selling simple snacks or sweet drinks to keep you cool on hot days. It’s honestly a great spot to sit down and enjoy a little bag of duros or chicharrones.

You might spot a series of large concrete globes with grilles that look almost like medieval knights’ helmets. These were old lights used to illuminate the courtyard at night, but alas, they have seen better days and no longer work. But one can imagine how these little globes of light would have looked like spectacles around the grass as the sunsets.

The Faculty of Architecture Building

On the opposite side of the Islands, we can see the modernist gem which holds the Faculty of Architecture. I love studying at this building from afar before getting up close. From far away, you can really appreciate how the building is meant to resemble a snake as it moves along the earth. Like a wave represented in the various undulating arches. The building was designed by architect Jose Villagran. As it was to host the faculty of architecture, they really wanted this building to embody the ideals of the architectural school. And provide a modern building for the students who studied there to aspire towards creating.

One of the most modern techniques utilized in the construction was the addition of “brise soleil” or sun breakers. These are the red slats that run along with the second storey of the building. Brise soleil was a new architectural feature that allowed buildings to control and reduce the sunlight that beats down on the building by deflecting the light. This meant that you wouldn’t need to waste excess energy on powerful air conditioning even in the peak of the summer.

The Conquest of Energy Mural

Head around to the north walls from the front of the building, where you can find an incredible mural by Chávez Morado. José Chávez Morado was a Mexican muralist who worked in the same circles as the other artists we have seen this far. Chávez Morado created three different murals for the campus. But unfortunately, the third mural, created in vinyl, did not stand the test of time.

Thankfully the other two murals were made of Venetian glass mosaics. Chávez Morado travelled to Italy to study the production of mosaics and how their old masters managed to capture such brilliant colours in the glasswork. When he returned to Mexico, this masterful technique was highly regarded by his peers, who marvelled at the vibrant colours he managed to produce. Unlike anything anyone had seen before and a highlight for the campus.

The name of this mural is the ‘Conquest of Energy.’ Reading the mural from left to right, we can see the primitive Mexican people cowering beneath a sickly tree. They are cowering in fear of the large jaguar which leaps above them, perhaps stalking them for food. With nothing but the barren tree to protect them they surely await death…

The Myth of Prometheus

But then we see one man come forward, holding a lit torch, which he uses to ignite the fire. The man is perhaps an allegory for Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods to give to people on earth to lead them into the future. This man is seen dressed in animal skin, perhaps that of a jaguar, showing man’s dominance over the animal kingdom with the introduction of fire.

Fire would both keep these people safe and move them forward into a new era. As fire as the through-line that connects each of the parts of the mural, the colouring of the entire piece is so fiery! In the middle section, a series of men then carry the flame in their hands. They walk towards the right of the frame, with each step the men start walking more and more upright in their stance.

Atomic Ressurection

Toward the right, two men hold their palms out towards each other, almost touching a floating atom which stands between them. Representing the fusion of the atom. But below the image of the atom, we can see a man collapsed in the arms of a beautiful woman dressed in a red robe. The man’s ribs are sticking out, and he looks sickly. And yet, in his eyes, there is a spark as he gazes up towards the atom. As if the atom is about to resurrect him.

Just to the women’s right, we can see the sick man transformed. His energy and strength have returned as he stands with his arms spread wide in triumph. A ghostly blue figure, the same colour as the energy around the atom, stands beside him. Perhaps the spirit of the atomic energy that brought him back to life.

The final piece to study is the small tree at the bottom right. It resembles the lifeless tree we saw in the first part of the mural, but this tree is covered in bright green leaves and is blossoming with fruit. Fruit is the symbol of knowledge. Knowledge that has been growing with the discovery of atomic energy.

The Return of Quetzalcóatl

Another mural by Chávez Morado can be found inside the courtyard of the school of architecture. Depending on the day, entry into the building might be restricted but usually, if it’s open, if anyone asks, just mention you are on your way to see the mural. The courtyard is home to a few picnic tables for students to eat at, highlighted by this incredible mural. Perhaps because of its slightly more obscure location, this mural is almost perfectly preserved.

Quetzalcóatl

It features a scene all about Quetzalcóatl. Quetzalcóatl, the feathered serpent, was the god of winds and rain. But he is also best known as the creator of the world and humanity. In this scene, Quetzalcóatl has transformed himself into a giant raft. He carries on his back seven representatives from various cultures around the world.

Cultural Representatives

From left to right we can study each one of the different cultures. We first see the image of an Egyptian pharaoh. Beside him sits the hooded figure of a Franciscan friar, a symbol of Christianity. The blue-winged figure that sits behind them is perhaps an angelic creature riding beside the friar.

The central figure has the body of a naked man but wears a large colourful mask. The mask is meant to resemble the head of Ehecatl, who was the pre-Columbian god of the wind. He works alongside Quetzalcóatl to propel their boat onwards. The man to the right of Ehecatl carries two golden chalices. He represents Mesopotamia. Next, we can see the toga-clad Greek representative and beside him sits the image of the bodhisattva in prayer as a representative of Eastern cultures. The final image is of a Muslim man wearing his turban and brown robes.

To the left of the boat, you can see the image of an Aztec pyramid in the distance being attacked by a series of swords and spears. Perhaps the omen of the Spanish Conquest that would follow. Behind the entire scene, there seems to be a fire burning. Fire is often a symbol which refers to eternity, as in the “eternal flame.” This means that even when invaders try to come in and rid your nation of all that is sacred, your culture will remain eternal. In the hearts and minds of the people.

Chemistry Building Mural

Continuing east, head into the large open courtyard facing the Chemistry Building. You’ll recognize it right away as the Chemistry Building by the giant Periodic Table seen on the windows. The ingenious designers used the square shapes of the windows to create a mural plastered onto the inside to create a larger-than-life Periodic Table.

Cosmic Ray Pavilion

Crossing northeast across the basketball and sports courts head towards the front of the Faculty of Medicine. On the way towards this building, make a quick stop beside the Cosmic Ray Pavilion. The relatively small pavilion is made of concrete and once contained two labs used to study cosmic rays and nuclear disintegration. Although it is small, it displays some exciting advances in concrete architecture. Because of the slightly dangerous nature of these experiments, they were required to be located outside the main buildings. Today it remains a memory of this period of discovery at the university.

Faculty of Medicine Mural

Beyond the Cosmic Pavillion is the brilliant mural outside the Faculty of Medicine. The mural is called “La vida, la muerte, el mestizaje y los cuatro elementos,’ by Francisco Eppens Helguera. This translates to “Life, death, mestizaje, and the four elements.” The word “mestizaje” means “of mixed race,” and refers to mixtures of race and culture. Much of the population of Mexico City is made up of mixed races. When the Spanish first invaded, many Spaniards had “relations” with the indigenous people. Involving consensual and non-consensual relationships. This produced a new race of half Spanish, half indigenous people.

Despite having some Spanish blood, mestizajes were considered lesser in their social status than purebred Spaniards. But they were also not entirely accepted by the purely indigenous community. This social cast system and complex cultural history are still something that Mexico struggles with even today. The three faces on one head in the centre of the mural represent the idea of multiple races and cultures living inside one body.

Surrounding the rest of the mural we can see many of the Aztec gods we studied in the Central Library mural. But mirrored here in a series of surreal scenes. We can see the feathered serpent encircling the background. We can see Quetzalcoatl’s fangs and round eyes looking out at us at the bottom right of the mural. The four elements, wind, air, fire and earth are all woven into the design seamlessly along with a series of pre-hispanic symbols.

Overcoming of Man through Culture

Heading off towards the left, you can see the image of “La superación del hombre por medio de la cultural,” which means the overcoming of man through culture. The mural stands on the outside of the Faculty of Dentistry. It was painted by Francisco Eppens Helguera, who became most notable for his 1968 redesign of the Mexican coat of arms. Made up of glass mosaics it shimmers in the sunlight. The mural features a man emerging from the roots of a tree. But in the place where they should be ahead, the neck fades away into a bright blue flame. This image of a man embued with fire once more highlights the idea of the Promethean man bearing fire.

Almost like a shadow, behind the man in the front of the frame, we can see another headless body, this one dressed in the robes of a Franciscan priest. Behind him, the great wings of an eagle emerge out of the mountains. To the left of the figures, we can see a giant snake, the symbol of knowledge, crawling underneath the scene. The entire piece gives the viewer the message of man’s struggles to rise up, and only through culture is he given the strength to overcome.

Visiting the South Campus

This is the last mural we will study in our guide but if you’d like to keep exploring there are lots more areas of the campus to discover. You can consider hopping in an uber or jumping on one of the free campus buses to visit the southern part of the campus. On the south campus, you can visit the Outdoor Sculpture Gallery, the Botanical Gardens, the University Museum Contemporary Art, or Universum (The Museum of Science and Technology.) Or simply wander around the campus building to see more of what this incredible place has to offer.

Let me know if you enjoyed this tour of the wonderful architectural features of the UNAM campus! Tell me in the comments if you’ve visited this campus before or what your favourite university campus has been to explore anywhere in the world!

Happy Travels, Adventurers

1 COMMENT

Pino Shah

3 years agoComprehensive and rich in historical information, Thank you.