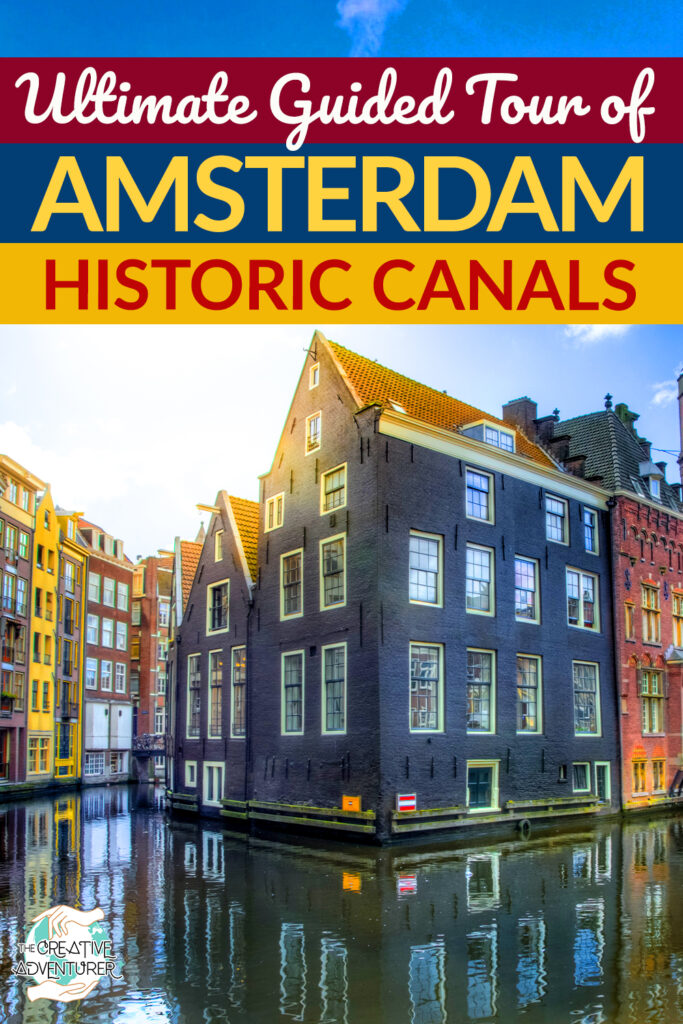

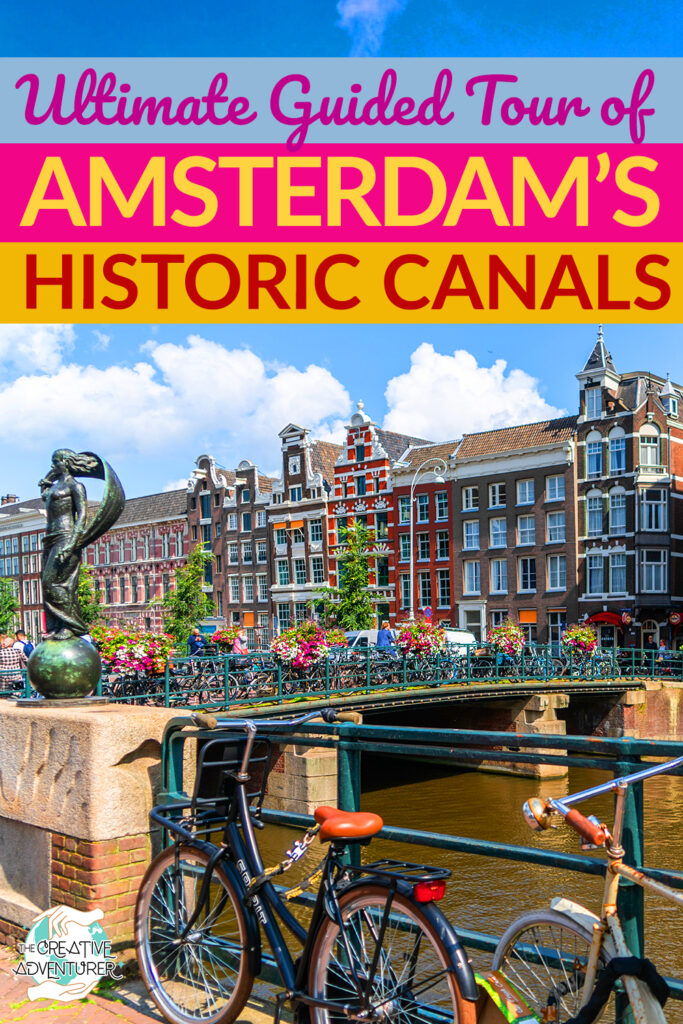

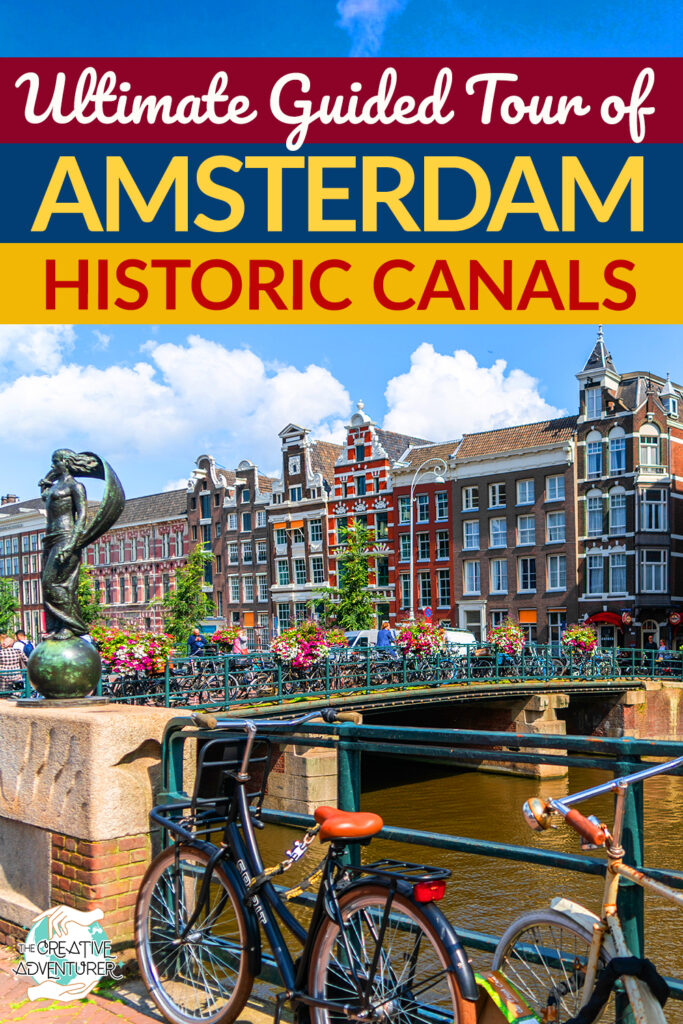

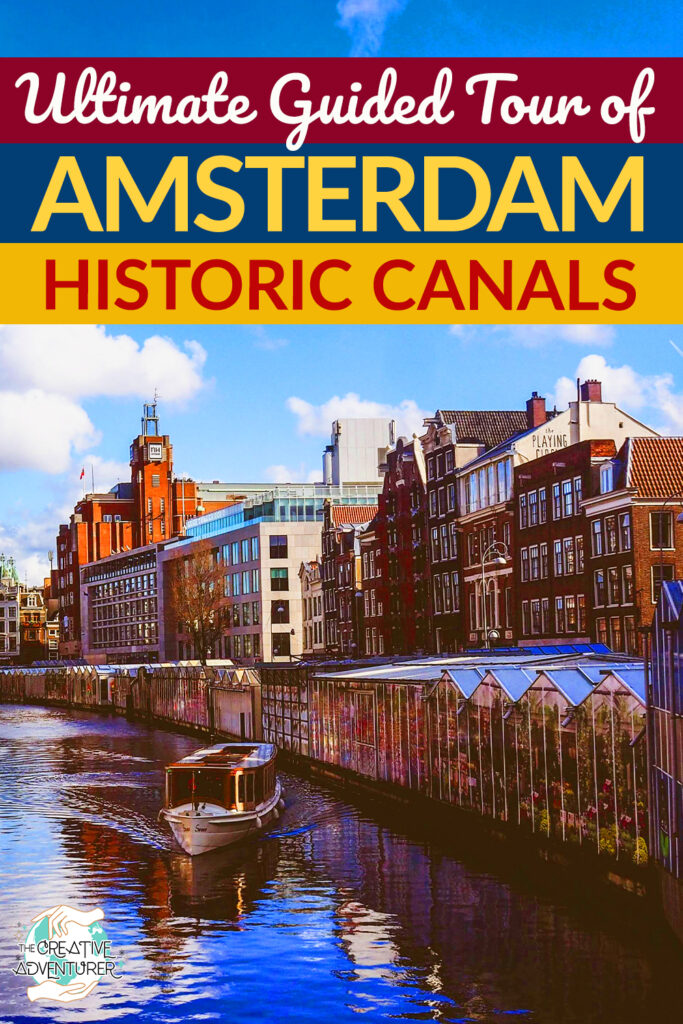

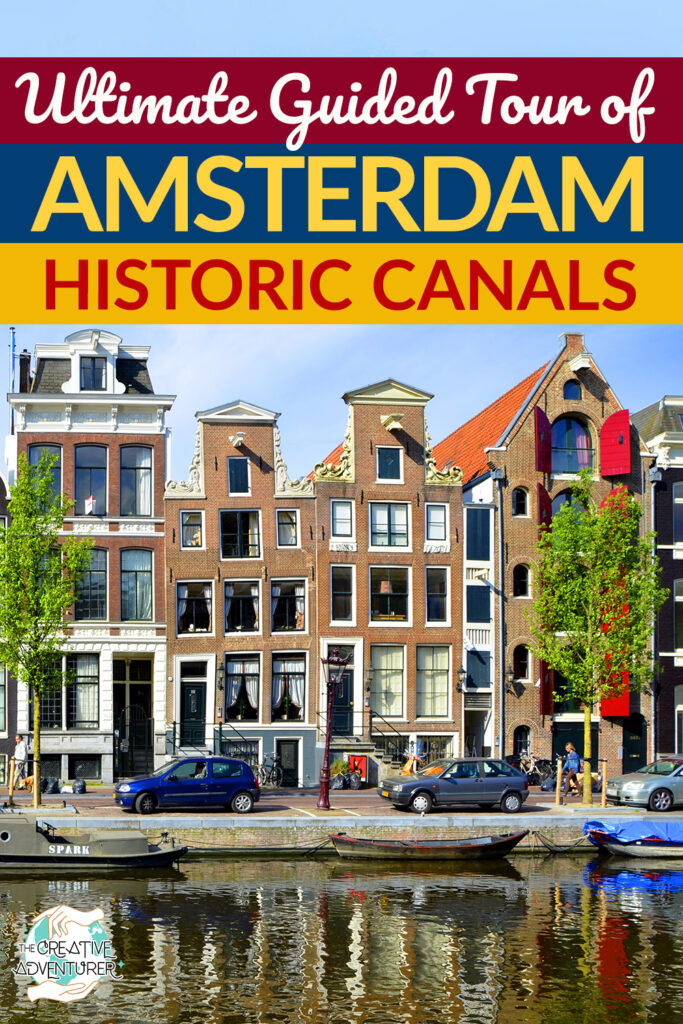

One of the greatest ways to explore Amsterdam is through its unique canal-facing architecture. Those iconic houses show up on postcards, magnets, tea towels and more. They feel like the de facto symbols of the city. But behind each one of their facades are the hidden histories and secrets of Amsterdam. There are over 90 different islands in Amsterdam connect by 160 gorgeous canals. Interestingly, Amsterdam has more canals than Venice and more bridges than Paris! Amsterdam’s architecture is some of the best-preserved architecture in all of Europe. The historic centre has over 7,000 registered historic buildings, so the entire island feels like a floating museum.

Most people opt to go on a boat tour, and rightly so, as it is one of the most authentic ways to explore Amsterdam. But a tour on foot allows you to spend more time studying the buildings up close. This way you can get a real sense of the atmosphere and environment of different neighbourhoods spread across the city. A walking tour is a great idea as an intro to the city. You’ll get a taste and decide for yourself where you might want to return to study in greater detail. Don’t worry too much about being on the right side of the canal as we go. You can easily see these buildings from across the canal. But you can always cross over one of the many bridges in the city should you want to get a closer look.

- How Long is the Tour?

- Amsterdam History

- Types of Gables

- Walking Tour Starting Point: Brouwersgracht

- Eenhoornsluis

- Prinsengracht

- Jordaan Neighbourhood

- Keizersgracht

- Lauriergracht

- Beudekerbrug

- Reguliersgracht 92

- Magere Brug, the Skinny Bridge

- Amstel

- Herengracht

- Koningssluis

- Melkmeisjesbrug

- Singel Canal

- Blauwburgwal

- The Torensluis

- Bloemenmarkt

- The Dancing Houses

- Grimburgwal

- Kloveniersburgwal

- Oudezijds Voorburgwal

- House at the Three Canals

- Agnietenkapel

How Long is the Tour?

This is a full-day walking tour that takes you across the entire city! If you feel like splitting it up, feel free to customize the tour yourself! This way, you can spend some extra time in any of the museums listed. That is the joy of self-guided tours, after all. We will start our tour in the quiet northwest corner of the city in the Jordaan neighbourhood. Then we slowly make our way over to the southeast end.

Amsterdam History

Amsterdam began as a small fishing village. The village was located behind the large dam which protected the city from the overbearing Amstel River. The name “Amsterdam” comes from the location along the “Amstel” river and the “dam” which protected it. In less than 200 years, from the 16th to 18th century, the city of Amsterdam’s population exploded! It multiplied from 30,000 residence to 160,000 residents almost overnight. The city was a melting pot for immigrants from all over Europe. At the time, the Netherlands had a very tolerant climate towards refugees. With this came a massive influx of people from France, Portugal, Spain, and much of the Jewish population from Antwerp.

The Canal Expansion

Back then, Amsterdam was just this tiny island overflowing with people. The city needed to find a way to expand the city and cope with the growing population. So, the city council decided they would follow what the Italians did in Venice. They created a series of canals that spread out around the city. But unlike the winding, a spider web of canals in Venice, the design of the Amsterdam canals was very structured. They run in a half-moon shape around the bay encircling the historic medieval centre. Historians also call this the windshield wiper design.

Grachtengordel

The newly formed canal belt neighbourhood was called the Grachtengordel. “Gracht” translates to the word “canal” so literally, this was called the canal district. This new area would be designated for inhabitants. A fourth canal was added, the Singel Canal, which would be used for defence.

Building the canals was a pricey business. So the city offered wealthy merchants and bankers the opportunity to buy plots of land in these prestigious areas. This helped them secure the funds they needed to build the waterways. A portion of the outer canals was reserved for industrial use. As these factories were known for being loud and smelly the city wanted to keep them as far away from the aristocrats as possible.

Creation of Canal House

Many of the houses you see in Amsterdam are built atop a series of wooden poles. If you were to scan a cross-section of the city, you’d see it look like a giant pin cushion. How many poles are there? Some say it’s as much as eleven million! The Amsterdam Centraal train station alone stands atop 9,000 poles. Each pole needs to be around 15-20 meters tall to be struck down deep enough to support the houses built atop it.

Amsterdam Roof Gables

During the 17th century, it was considered gauche to see the roof of a house from the street or canal. This is why you see so many of Amsterdam’s houses featuring ornate and prominent gables. A roof gable is a section of wall between the edges of a dual-pitched roof. It provides both an aesthetic and functional purpose. Many of the gables in Amsterdam also feature sturdy winches in the center. These were installed to help lift heavy items up to the upper floors of the home or warehouse.

Types of Gables

The uniquely shaped gables are one of the most notable features of Amsterdam’s architecture. There are four primary designs you can see across the city. These include; the stepped gable, the bell gable, the neck gable and the spout gable. Each type of gable corresponding to a different period of time, like spotting fashion trends through the ages.

The Step Gable

The step gable was built in 1600-1655. It resembles a set of stair steps ascending from either side, ending in the rooftop. As this is the oldest style, it is one of the rarest to find.

The Spout Gable

The Spout gables were made from 1620 to 1720. These less ornamental designs signified the presence of a warehouse rather than a residence. The gable was formed into an inverted funnel with a rectangle block on the apex of the roof. This kind of gable was reserved for merchants. As it was used to signal warehousing and trade.

The Neck Gables

The neck gables were famous from 1630 to 1780. The gable resembled the idea of the human neck, slender and extending upwards. The thin rectangular extension goes up in the middle decorated with sandstone ornaments called “klauwstukken” or claw pieces, often featuring shell motifs. These symmetrical designs were popularized by the Louis XIV style. They were implemented to give the illusion of widening the facade.

The Bell Gable

The Bell Gable was built from 1660 to 1790. The ornate design resembled a church bell, and these designs also often featured more ornate sandstone scroll motifs. They were designed as an evolution to the nack gable.

Why are the Houses so Thin?

Another unique aspect of houses in Amsterdam are their width. The houses are designed to be tall and narrow. But this was originally not originally an aesthetic choice. Back then, taxes were calculated based on the width of the house, not the height. So the answer to building a large home without high taxes was to build upward.

Types of Hosues

There are two main types of houses you see along the canals. They are easily identifiable if you know what you’re looking for. There is the koopmanshuizen (merchant warehouse) and then the herenhuis (residential mansions and townhouses). Merchant houses were designed to work on a split-level design. The lower levels near the water could operate as warehouses and the upper levels were used as the living quarters. Everything from spices, tulips, coffee and more were stored here. To identify the warehouses you need only spot the large wooden shutters. These were only added to merchant’s houses. The shutters when opened allowed goods to be hoisted in up to the upper levels which allowed for more storage space. When closed, the large wooden shutters helped keep out the heat and sunlight to preserve the goods inside.

Walking Tour Starting Point: Brouwersgracht

Our tour starts on the Brouwersgracht. This canal was developed in the 17th century just north of the residential canal belt. It was a canal built for large warehouses. The location near the mouth of the river allowed quick access for ships returning piled with goods. The Brouwersgracht, or the Brewers’ Canal, was named as such due to the number of breweries in the area. The location not only made the delivery of goods simple, but it also meant these warehouses had the best access to fresh water. Essentially for breweries and distilleries.

Brouwersgracht 218

On Brouwersgracht 224-218, we can see examples of neck gables. The house at #218 features a neck gable decorated with Doric pilasters that extend up in the style of Dutch Baroque architecture. The facade features three “oeil-de-boeuf” or “ox eyes”. These are small rounded windows (although these windows have since been bricked up.) Oeil-de-boeuf windows were popular design trends in Amsterdam and they pop up all over the city.

Hanging from the centre of these gables is a sizeable protruding hook. These hooks were used alongside a pulley system to move heavy items into the home. Although they were originally designed for the warehouses, to bring in spices, cotton or cocoa, in the residential homes they were used to move heavy furniture in and out.

Brouwersgracht 204-212

A group of 17th-century warehouses sit at Brouwersgracht 204-212. Standing on the top of the gables along this series of warehouses are a variety of Green Deer sculptures. The one in the center looks straight out over the canals, seemingly on guard. Whereas the two on either side lie in repose, looking in towards the centre deer. When the family built the warehouses in 1640, the deer were always the crowning glory of the gables. But they disappeared hundreds of years later. When the area residents discovered some old drawings of the warehouses that featured the lost deer, they collaborated to have them reconstructed. Although they are now made of plastic (as to not disturb the structural integrity of the gable), it’s nice to see the love that the neighbours have for their neighbourhood history.

Brouwersgracht 196-188

Many of the houses along Brouwersgracht contain those iconic brightly coloured window shutters. Used to identify them as warehouses. You can see more examples of these along Brouwersgracht 196-188. All of these warehouses were built around 1636. In 2007 Brouwersgracht was voted the most beautiful street in Amsterdam by readers of Het Parool out of 150 nominations. And one can really see why. The canal is a lovely blend of all the most famous Dutch architecture. It is also home to a series of scenic houseboats that float along the canal. But since the canal is located far enough from the busy tourist centre, the area still feels peaceful and quaint.

Brouwersgracht 174

At #174 Brouwersgracht, you’ll find a vast building with the widest roof gable found anywhere in the city. Topping the centre of the gable is Amsterdam’s famous coat of arms. The coat of arms of Amsterdam consists of a large red shield with a black strip down the center. Punched along the vertical black stripe are three silver Saint Andrew’s Crosses. These three crosses are seen all over Amsterdam, either accompanied by the shield or sometimes just on their own. Unlike what you might think, “XXX” doesn’t stand for anything untoward or x-rated. St. Andrew is the patron saint of Amsterdam as he was a fisherman just like the earliest residents of the city. When St. Andrew was martyred, he was placed on an X-shaped cross, and the X became a symbol for the saint.

But why are there three Xs? Well, there are a few theories. One theory states that they represent the three formidable rivers Amsterdam controlled. Another is that it stands for the holy trinity. But my favourite theory is that they represent the three threats Amsterdam needed to protect itself against. These were fire, flood and plague.

Eenhoornsluis

Just a few steps from the Brouwersgracht is the great Eenhoornsluis or Unicorn Lock. This is one of the 16 “water locks” found around the city. These water locks were built in the 17th century to control the water levels inside the canals. They were meant to protect the town from flooding in from the swelling seas. Previous to 1916, these water locks actually allowed fresh ocean water into the city. But in 1916, a great flood caused much damage to the city. After this, the Southern Sea dike was built to prevent such a flood from ever happening again. This resulted in the transformation of the city’s water to be freshwater only, but the payoff was worth it in the long run.

Prinsengracht

From the bridge, turn down onto the Prinsengracht. Prinsengracht, or the Prince’s Canal, was named after the Prince of Orange. This is the fourth of the four main canals belonging to the canal belt. The Canal Belt, and rings it formed around the city, would go onto give Amsterdam its distinctive crescent shape. The four canals which make up the Canal Belt are the Singel, Herengracht, Keizersgracht, and the Prinsengracht. The Prinsengracht is the longest of all the canals, stretching out over 3 km, on the outer edge of the city. The epic construction of the canal began in 1612 and took over 50 years to be completed.

Café Papeneiland

As we turn on Prinsengracht, we first stop off at the Café Papeneiland. This is the oldest cafe in Amsterdam, established in 1641! In the 16th century, during the Dutch Protestant Reformation, the government outlawed Catholicism. This meant all Catholics had to practice in secret or abandon their religion altogether. Many underground Catholic churches were built in response. Tunnels ran throughout the city to connect secret entrances to these churches. And this cafe was once one such location. The cafe’s name translates to “papists’ island,” as this part of town was known as a sanctuary for Catholics. The tunnel entrance is still located in the basement. If you order something from the bar (preferably their amazing dutch apple pie), ask the bartender nicely to show you the old entrance.

Jordaan Neighbourhood

The area along the western side of Prinsengracht is better known as the Jordaan Neighbourhood. The canals closer to the historic center were generally reserved for the wealthy residents of Amsterdam. So the Jordaan Neighbourhood, away from the city centre, was a low-income area and somewhat of a slum. The roads and canals here are more slender than the rest of the city. This was done to save money on construction but resulted in what was seen as a more crowded district. It wouldn’t be until much, much later in Amsterdam’s history, that the area was gentrified into what we see today. Now, the Jordaan is one of the hipper parts of town.

But back in the 17th century, the area was densely populated by immigrants and refugees. Many of these refugees were from France. The name of the area, “Jordaan,” is derived from the french word “Jardin,” meaning garden. Many of the streets off of Prinsengracht are named after flowers.

Noorderkerk

Continuing along, you’ll come to the large Noordermarkt square. The square is dominated by the imposing Noorderkerk or North Church. The North and West Church (which we will see later) were financed by the same merchant guild who hired the same architect, De Keyser, to design them both. The North Church, built in 1620, was meant to be the “people’s church.” It was intended as a simpler version of the more ornate West Church. The Noorderkerk has a symmetrical, cross-shaped layout, reflecting the ideals of the Renaissance and Protestantism. De Keyser’s unique design combines an octagonal floor plan with a structure shaped like Saint Andrew’s cross. Four arms of equal length spread out around the building giving it almost a circular appearance.

The “people’s church” was a polite way to distinguish the population that attended. This town area was home to Amsterdam’s more impoverished population. The wealthy merchant didn’t want to associate with them. They were mainly fishermen, and apparently, the smell of fish was something the wealthy merchant didn’t have the stomach for.

Van Brienenhofje

Located along Prinsengracht from #85 to 133 is the old Van Brienenhofje. This was one of 13 different breweries which were situated along Prinsengracht. When the brewery closed, it was transformed into an almshouse for the elderly. Today it is still used as a housing association for the poor.

Prinsengracht 175

At Prinsengracht 175, you can see an old house that dates back to 1661. On the front of the house, are a series of gable stones. They are carved into the shape of a sheep, an ox and a lamb. These gable stones can be found on many of the older buildings around Amsterdam. They were called gevelstenen and used before there was an established numbering system along the canal. These symbols also were used to identify the occupation of the owner inside. This also helped the illiterate population of the city during the middle ages find different shops and businesses they required. Spotting these stone tablets makes for a fun eye-spy game as you explore the city!

Keizersgracht

We’re going to take a quick detour over to the Keizersgracht by turning left along Prinsenstraat. The Keizersgracht (also called the Emperor’s canal) is the third canal in the canal belt. It was named after Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. During the wintertime, if the weather is cold enough, the water freezes over thanks to the water locks which stop freshwater from entering. This allows residents to skate up and down the canal, a great way to get around during the winter. The canal is 31 meters wide, making it the widest of the waterways in the canal belt.

Keizersgracht 44

The red shutters of #44 Keizersgracht mark it as a traditional merchant warehouse. But what makes this house different are the stepped gables. Most merchant houses didn’t feature these ornate gables as they were primarily used on residences. This house is also unique as the contents of the warehouse were whale blubber. Large cement pits were dug out in the basement where the whalers could store up to 50,000 litres of whale blubber.

Rode Hoed

The Rode Hoed (Red Hat) announces itself to the public in large red letters as you pass by. While the house looks almost like a church, it was initially a hat makers shop until 1629. After that, the building was purchased by the Remonstrants Brotherhood (a sect of Protestants). Like the Catholics, they needed to practice in secret. They built their underground church here, where they practiced until 1957. After that it was sold to a TV station. Thankfully, the station protected the appearance of the exterior for future generations to appreciate.

Keizersgracht 123

The house at Keizersgracht 123 is better known as the “House with the Heads.” The house was built in 1622 for merchant and art lover Nicolaas Sohier. It was built by city architect Hendrick de Keyser in high Dutch Renaissance style. The roof has been given that illustrious stepped gable design with decorative obelisks, pilasters, claw pieces and swathes of flowers blooming between the windows. Located above the pediments are these wonderful lion masks with their mouths wide open as if in a mid growl.

The house’s name comes from the six sculptural heads on the facade, located just above the first floor. These six heads were initially rumoured to represent six robbers who had once attempted to break into the house. They were caught in the act by the kitchenmaid and were beheaded with her own meat cleaver! Sadly, the story is nothing more than gossip but it makes for a great rumour. The heads acutally represent the six gods; Apollo, Ceres, Mercury, Minerva and Diana.

Keizersgracht 177

The large brick mansion at #177 Keizersgracht is called the Coymanshuis. It was designed in 1625 by Jacob van Campen for two wealthy brother who were both bankers. The brothers made their fortune in silver and iron. They had huge families, one brother having six children and the other having ten! So, in turnn, they require a very large manor to house all those kids! Architect Jacob van Campen would go on to design the Amsterdam City Hall. He used this house as his winning portfolio piece to get the opportunity to work on the great city hall.

Homomonument

On the other side of the canal, opposite the large and imposing Westerkerk, is a series of steps leading down to a triangular platform. This is the Homomonument, a memorial to commemorate gays and lesbians citizens who were killed by the Nazisduring WWII. Pink triangle badges were used in concentration camps to identify gays and lesbians and the triangular design is used repetedly here to memorialize those actions. The Homomonument was designed to “inspire and support lesbians and gays in their struggle against denial, oppression and discrimination.” An estimated 15,000 people were sentenced to concentration camps during WWII, many of whom, never returned.

Astoria Building

Although there aren’t many art nouveau-styled buildings in Amsterdam, you can find one of the greatest here at Keizersgracht #174. This is the Astoria building, built in 1904 to serve as the head office for the Eerste Hollandsche Levensverzekerings Bank. Towering over the rest of the city, the Astoria was the first office tower ever built in the Netherlands. The Dutch style of art nouveau, also called the Nieuwe Kunst, is a much more restrained version of the art style found elsewhere in the world. The most impressive part of the building is the giant mosaic located on the facade depicting an angel protecting a young woman beside a small child.

Anne Frank House

Turn back onto the Prinsengracht canal and make your way to Prinsengracht #263. The house is easily spotted by the long line of people outside. They are all waiting to see the famed Anne Frank House. It was here that little Anne Frank wrote her seminal diary. This book went on to ignite, inspire and inform young people the whole world about life during WWII.

The Secrets of the House

It was in this house that Anne and her family hid from the Nazis. The house was initially built in 1635 by Dirk van Delft, but the canal facade was renovated in 1740. The lower levels with their wide stable-like doors were initially used to house horses. Later, when Otto Frank bought the house, the space was used as a warehouse for household appliances, piano rolls, and spices. In the back part of the house, was concealed from the street. From the outside, you couldn’t make out the back extension that allowed Anne and her family to hid. A trick bookshelf was installed to give access to these large secret apartments.

Sadly, after hiding for two years, they were discovered by the Nazis during a raid and were sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Anne’s father Otto was the only family member to survive. The employees who worked in Otto’s factory came back to retrieve anything left behind by the Nazis. Luckily, one of these items was Anne’s diary. When Otto returned to Amsterdam it was his life’s mission to publish the book. Not knowing how widespread her musings would become. If you are interested in visiting the museum, be sure to book tickets WELL ahead of time. I’m talking like two months early in some cases! You can also line up in the afternoon for day-of tickets but there is no guarantee you’ll get in and the line tends to be hours long.

Westerkerk

Opposite the Anne Frank House is the 17th-century protestant Westerkerk. This church is most notable for its 87-meter tower, which can be seen all across Amsterdam. The top of the building is capped with the brightly coloured gilded Imperial Crown. The symbol of the imperial crown belonged to the Holy Roman Emperor, in honour of Maximilian I, archduke of Austria and ruler of the Low Countries. When Maximilian travelled to the Hague in 1484 he fell ill. He prayed that if he recovered he would make a pilgrimage to Amsterdam, where the miracle had been performed. When he was indeed healed, he granted the use of his coat of arms to the city of Amsterdam. The crown is covered in bright blue enamel and even decorated in shining jewels to look as realistic as possible.

The interior of the church is rather plain, painted in white with natural stones. The main feature of the interior is the 36 large windows which allow sunlight to pour in from any angle. There isn’t a single building surrounding the church that obstructs the light flowing in. The white painted interior highlights the glowing luminescence produced by these great windows.

Nieuwe-Wercksbrug

Walk up along the Nieuwe-Wercksbrug bridge to get a beautiful view down the canals. Standing on the bridge, you are walking along Rozengracht street. Rozengracht street translates to “rose street,” but back in the 17th-century, the area was nothing of the sort. The Rozengracht is one of the six filled-in canals located in the Jordaan neighbourhood. The canals had to be filled in because of the poor hygienic condition in the water due to the pollution. People threw everything from garbage, dead animals and human waste into the canal. The street literally smelled so bad they had to fill it in. Now you might understand the irony of giving it such a flowery name.

Reesluis

Reesluis is the name of the bridge which crosses over this part of the Prinsengracht. From here, you have a fantastic view of Westerkerk’s giant clock tower that looms over the canal. The bridge is named after the Reestraat, which continues out to the east. The street’s name translates to “Deer Street.” This area of town was popular with animal skin traders and craftsmen who worked in the leather industry. The bridge is one of the older bridges in the area, built before 1625.

Lauriergracht

From here, we are taking a short detour to the east along the Lauriergracht. The Lauriergracht, or the “Laurel Canal,” was a popular place for artists to live in the 17th century. I definitely find this canal contains many hidden artistic flourishes from bright stained glass windows, colourful exteriors and even just little ornate stonework hidden here and there. They are small flourishes but definitely a unique characteristic of the area.

Lauriergracht 23

Built in 1658, this home was a typical 17th-century example of the fanciful neck gables of the time. This one features two huge lions set into claw pieces. The lions look like they are on the prowl, protecting the home from intruders.

The Houseboat Museum

Turn back to Prinsengracht until you reach the corner of Elandsgracht and Prinsengracht where you’ll find the Houseboat Museum. Since there are over 800 houseboats in Amsterdam, you’d be remiss in visiting the city without going inside of one. And unless you’ve booked one for your hotel stay (a great idea, by the way) or you know someone with a houseboat, this might be your only chance to see the interior of one in person. This houseboat dates back to the 1960s. It has such a retro vibe and still displaying all the ingenious ways people make the small spaces work for them as living quarters. There isn’t a drawer or cabinet not squeezed into place to make these floating homes just like the real thing.

Prinsengracht 300

At #300 Prinsengracht we’ll find another beautiful example of the stone house symbols. This one features a red fox with a blue sparrow in its mouth. The house was built for furrier Dirck Hendricksz Hooghvelt who made his living selling fox fur clothing. The house was originally called ‘De Witte Vos’ (meaning the white fox) until 1767 when the stone tablet was repainted white and the house went by the name ‘De Roode Vos’ (the red fox.)

Beudekerbrug

In 1949, while walking across the Beudekerbrug, singer-songwriter Pieter Goemans was inspired to write the famous song ‘Aan de Amsterdamse Grachten‘ (‘On Amsterdam’s Canals’). It is one of the most popular songs celebrating the city. You’ll often hear it played on street organs across the Netherlands. When the author died in 2000, his ashes were scattered here in the canal. The plaque on the bridge commemorates his contribution to the history of Dutch music.

Palace of Justice – Prinsengracht 443- 436

From the corner of Prinsengracht and Leidsegracht, we can see the great former Palace of Justice. At the corner, the building has a much different style than the neo-classical facade further along. The entire structure was once the old ‘Weeshuis‘ or orphanage. This Weeshuis was designed to serve the poorest of Amsterdam’s children. Two small stone carvings on either side of the doors on the old brick building show the images of the nuns. The nun who worked in the orphanage are seen holding hands with the small children in the frame. Despite the updating of the rest of the building this small memento from history remains.

The orphanage was renovated into the Palace of Justice in 1825 by architect Jan de Greef. Greef was working under the stylist trends of the period. These were heavily inspired by ancient Greek architecture. The building features large stone columns, Corinthian capitals and heavy stone balustrades. On the second-floor facade, you can see a stone carving with a poem attributed to Jacob van Lennep. It reads, “Under your rule, Serene Willem! Is this Asylum rebuilt, and consecrated to Law and Justice.”

Prinsengracht 769

At Prinsengracht 769, you’ll find the old Prinsengracht Hospital. The original hospital was built in 1857 after the cholera epidemic in the 1850s. The hospital remained open for over 150 years, eventually closing in 2015. A modern co-working space company bought the property. They wanted to transform the individual hospital rooms into rentable desks spaces and meeting rooms for digital nomads and start-up companies. While the interior has been modernized, the facade remains much unchanged from the days when it served as a hospital.

The Deutzen Hofje

Facing out along the canal’s bend is the Deutzen Hofje at Prinsengracht 857. Hofje is the Dutch word for a courtyard with almshouses around it. Hofjes have existed since the Middle Ages providing housing mainly for the elderly. The house was built in 1695 with funds from a wealthy Amsterdam resident. She bequeathed the house over to the city to become free housing for older servants who couldn’t work anymore. On the front of the house are the words, “A comfort to the poor, an example to the rich.”

Reguliersgracht 92

At the corner of Prinsengracht and Reguliersgracht is an old red-painted building. Take note of the interesting sculpture of a stork peeking out over the niche above the doorway. The building was first built in the 17th century for a popular midwife. She used the stork as a symbol and de-facto advertisement for her business.

De Duifbrug

De Duifbrug or the Dove Bridge has also been called the “tunnel of love.” The original name came from the fact the bridge was located next to the old De Duif church. But the nickname was given as it is thought to be one of the most romantic spots in the city. Standing on the bridge your vantage point looks out over at the seven different famous bridges that surround the area. When illuminated at night, it is one of the most magical places in the city!

Brasserie Nel

Set back on the Amstelveld, is a charming tree-lined square. Located right inside is the old Brasserie Nel. The building, which houses the trendy restaurant with a picture-perfect patio, was built in 1668. It originally served as a temporary church before the De Duif was constructed. The restaurant is a great place to stop if you’re looking for somewhere to grab a bite to eat or just have a refreshing glass of beer!

Magere Brug, the Skinny Bridge

Make your way down to the Amstel River to see the Magere Brug or “Skinny Bridge.” Considered by most to be the most beautiful bridge in the city. The Magere Brug is a bascule bridge or draw bridge. These bridges can be raised to provide clearance for large boat traffic to pass through. The present bridge was built in 1934 to accommodate these large boats which couldn’t pass under the original stone bridge.

The first incarnation of this passage across the river was installed in 1691. Back then, it is said that the bridge was created by two sisters who lived on opposite sides of the Amstel river. Each one wanted to be able to visit one another every day without having to jump into a boat. But the women weren’t super-wealthy and could only afford to build a very narrow bridge. Hence the original name “skinny” bridge. Walk out onto the bridge for some of the best photo opportunities in the city. The view looking out at the Amstel River as well as the view of the bridge and houses behind it are both stunning photo spots.

Amstel

The name Amstel is derived from the Dutch word Amestelle. “Ame” meaning water, and “stelle” meaning solid, high dry ground. In the 12th century, the Amstel river was developed to serve as a commercial waterway by the very wealthy Van Amstel family. The family had been an influential dynasty in the medieval Netherlands named after the river from which they drew their wealth. The river is truly the lifeblood of the town and is one of the most important transit routes in Amsterdam.

Herengracht

Walk back to Amstel street until you reach the Herengracht. The Herengracht is the second of four Amsterdam canals belonging to the canal belt, located right behind the Singel Canal. The portion of the canal was built in 1612. Previously the area was a simple moat dug for the companies on the Singel canal to use. The name of the canal was given in honour of Heren Regeerders van de stad, the Gentlemen Governor of Amsterdam. Today it goes by the nickname the Gentlemen’s Canal.

Willet-Holthuysen Museum

After walking past so many of these canal houses, take this opportunity to step inside one for yourself! The house at Herengracht 605 was built for the mayor of Amsterdam Jacob Hop in 1685. It was passed down to each subsequent mayor until 1895, when it passed hands to Abraham Willet and Louisa Holthuysen. When Willet died, Louisa bequeathed the house to the city of Amsterdam. She gave it along with their collection of art, furniture and another interior decor to serve as the Willet-Holthuysen Museum.

The facade was renovated in 1739 to suit the new Louis XIV style. I adore the floral stone carvings, which look like they are real flowers growing out of the stone. Above the doorway is a large stone sculpture of St. George standing atop a slain dragon. Holding up the plinth is the head of an elephant whose trunk acts as a column holding up the entire stone tablet. The interiors all date back to 1895 and are a wonderful slice of that period of architecture, design and art in Amsterdam. Ticket prices for Adults are €12.50.

Gouden Bocht

The Gouden Bocht or Golden Bend was built as the most prestigious part of the Herengracht. Many people who originally purchased the land here were regents, mayors and traders. They were encouraged to buy a double lot to ensure their mansion felt grand and imposing. Most of the residents made their living importing and exporting goods from South America or the Dutch East Indies. The name “golden bend” came from the fact that the city’s wealthiest families seemed to be amassed right here along the bend.

Philips Vingboons and Adriaan Dortsman

Two architects were responsible for most of the structures along the Golden Bend. They were Philips Vingboons and Adriaan Dortsman. Philips Vingboons is known to be the originator of the famous neck gable design. Since Vingboons was a Catholic and the city was controlled by the protestant elite, he never had the opportunity to design any governmental or religious buildings in the town. These kinds of commissions would have brought in a substantial amount of money and fame for the artisan which he, therefore, missed out on.

Having two principal designers for one area meant the strip has a more uniform appearance. The styles they preferred featured very classical facades. Today, the Golden Bend keeps its name and is home to some of the largest banks and financial institutions in Amsterdam. Very appropriate.

De Bazel

Almost unmissable is the domanieering De Bazel building on the corner of Herengracht and Vijzelstraat. The building is the former headquarters of the Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij. The NHM was founded in 1824 by King William I to promote trade, shipping, shipbuilding, fishing, agriculture and manufacturing. One of their most important functions was supporting trade between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. The building was designed by the architect Karel de Bazel in 1919. It is nicknamed De Spekkoek, which translates to pork belly. It is named as such because of the alternating light and dark colours of stone that look like layers of fat in bacon. Spekkoek is also the name of a popular dessert with the same light and dark layers but made with cake.

Herengracht 446

The beautiful black brick facade at #446 was home to the Amsterdam regent family De Graeff. Andries de Graeff became the reigning mayor of Amsterdam in 1671. De Graeff was a Free Imperial Knight of the Holy Roman Empire. The Free Imperial knights were free nobles of the Holy Roman Empire, whose direct overlord was the Emperor. The upper gable is a stone shield with the De Graeff family coat of arms emblazoned on it. The coat of arms comprises two white swans and two shovels in either corner of the shield. The shovel represents the Herren von Graben family and the swans from the De Grebber family who joined together to form this new noble house.

Koningssluis

The Koningssluis bridge is one of the more uniquely designed bridges in Amsterdam. The original bridge was from 1662, but the current incarnation was made in 1921 by architect Piet Kramer. Instead of removing the entire old stone bridge, Kramer worked to integrate the ancient stones with new decorative wrought iron railings. He was inspired by the art deco fashion of the time. Don’t miss checking out the stone and brick corner of the bridge. These feature stone sculptures in the shape of mythical animals which are little hidden gems to discover.

Herengracht 394

The house on the corner of Herengracht and Leidsegracht is home to the ‘De Vier Heemskinderen‘ house. Notice the iconic house symbol above the doorway featuring a horse with four riders. This depicts the medieval story of the Four Sons of Aymon or the Heemskinderen. The house was built during the canal expansion in 1671. The high neck gable is decorated with carved floral garlands, which also embellish brick around the windows.

Herengracht 390-392

The houses along Herengracht 390-392 both feature incredible Dutch Baroque claw pieces adding a bit of interest to their neck gables. The houses were commissioned as a duo by the wood merchant Jan Teeringh and designed by Justus Vingboons. The ornately carved claw piece consists of a male and female figure leaning on the gable. A large cartouche was carved below them. On either side of the window are two large floral festoons, made to look like the stone facade has begun to bloom.

Museum of the Canals

If you are interested in learning more about the history of the canals in Amsterdam, make a stop inside the Museum of the Canals. Inside this historic grand mansion, you will travel back in time through over 400 years of history. You’ll be able to learn more about the history of Amsterdam and how the canals and the canal houses were built atop the water. Through minature scale models, 3D animations and interactive multimedia experience, you are really immersed into the world of Amsterdam’s history.

Herengracht 380

Herengracht 380 is probably my favourite house along the Herengracht. It looks so much different than the rest of the buildings along the canal, in a very distinctive style. It was built in 1775 adjoining three other buildings which once stood here. Sadly, in the 19th century, a great fire burned down the old buildings, and they all had to be demolished. But this new treasure rose from their ashes. The architect Abraham Salm was inspired by his time in Paris and the castles he saw in the Loire valley. The french style of architecture is a rarity to find in Amsterdam. The facade is covered in exuberant decorations, carved medallions, large sculptures, ornate balustrades and sandstone lilies (an iconic symbol of France). Although it was initially designed as a residence, it has since passed hands and is a government office building today.

Cromhout House

The houses along 370-364 are lovely examples of the lavish designs of the 17th century. Initially built for wealthy merchant Jacob Cromhout, the house was designed in 1660 in Dutch classicist style by architect Philips Vingboons. The lower facade is mainly classical but the gables are covered in a stunning array of intricate stucco decorations, which are emblematic of the Dutch baroque area. Pay close attention to the oval oeil-de-boeuf windows surrounding gorgeous floral motifs. Besides the neck, gables are claw pieces in the shape of swirling shells, another element of baroque iconography. The building was previously home to the beautiful Bible Museum, but it closed permanently in 2020. The home is now used for travelling exhibitions.

Bartolotti House

The Bartolotti House at Herengracht 170 was built in 1617 for Willem Bartolotti van den Heuvel tot Beichlingen. Willem had married Giovanni Battista Bartolotti, who came from a wealthy family of merchants from Bologna. Hendrick de Keyser was the architect and one of the most influential Baroque Renaissance architects. And this house is perhaps the best example of his work. The richly decorated facade has pilasters, masks, vases, claw pieces, extensive balustrades, and one of the most elaborate stepped gables in the city. The actual facade of the house seems to be bent at a slight angle, as the home is located in what was called the “small bend” of the Herengracht. On the facade are two large cartouches with the inscription, “Ingenio et Assiduo Labore” (by ingenuity and diligence) on the left and “Religione et Probate” (by religion and righteousness) on the right.

Herengracht 120

The charming black brick house with white accents at #120 was built in 1615 for cloth merchants Michiel Jansz de Lange and Adriaen Jacobsz van Noort. These merchants traded mainly with Norway, and they wanted to name their home after the King which they served. The style of the house with its large expansive windows is known as Amsterdam’s Urban Renaissance architecture.

Herengracht 81

One of the most spectacular historical houses is at #81. It announces its permanence with the date printed on the brick of 1590 when the house was first constructed. This is actually the oldest residential house in all of Amsterdam. It was initially a traditional merchant’s house, highlighted by those gorgeous wooden shutters. Before these brick buildings were constructed, in the medieval period in Amsterdam, all houses were built out of wood. But sadly, three great fires which ripped through the city destroyed all of these original homes. After the last fire in 1597, the government ensured all new houses were made in brick to help prevent future widespread fires. I adore the stepped gable located on this house; the red brick and white stone atop each step really highlight the shape and makes it so unique.

Melkmeisjesbrug

The Melkmeisjesbrug will take you from Herengracht over the Brouwersgracht. The word “Melkmeisjes” means “milk market.” When the bridge was first built in the 17th century, it was located near the large Dutch milk market. You’ll notice a set of three burgundy-coloured bollards situated on either end of the bridge. These were installed to prevent large vehicles from passing over the old bridge, which cannot withstand the weight. This was actually the first place they were installed. They are called the Amsterdammertje (Dutch for ‘little one from Amsterdam’). They are imprinted with three Saint Andrew’s Crosses from the coat of arms of Amsterdam.

Singel Canal

Walking south from the Haarlemmer Sluice we will come upon the last of the canals in the Canal Belt; the Singel Canal. The Singel encircled Amsterdam’s medieval centre, serving as a moat around the city until 1585. The Dutch word “omsingelen” means “to surround” as the canal literally surrounded and protected the medieval old town as a makeshift fortress of water. The trench was dug in 1428, making it the oldest of the channels in the central belt.

Singel 7

On the east side of the canal at Singel #7, we find the little slice of a house. It barely registers as a house at all when you pass by it. This is indeed the narrowest house in Amsterdam. The house is literally only a door’s width wide, with a singular window located on the second floor. Since we know that the property was taxed based on width, this building would have been a real penny pincher.

Ronde Lutherse Kerk

Although it’s now used as an event space, the imposing Ronde Lutherse Kerk or Nieuwe Lutherse Kerk was once the former New Lutheran church in Amsterdam. It was built in 1668 as the second and thus “new” Lutheran Church after the Old Lutheran Church had become too small. This building couldn’t cope with the many Lutheran immigrants coming into the city.

Lutheran architecture forbids the construction of bell towers, so instead, the architect wanted to make the great dome as the central focus of the church. Crowning the top of the dome is the Lutheran swan. The swan is a famous symbol in the Lutheran church because of its connection with Jan Hus. Hus was a key predecessor to the Protestant movement in Bohemia during the 16th century. His teachings had a strong influence on Martin Luther. When Hus was sentenced to be burnt alive, just before he said, “today you will roast a goose, but a swan will rise from the ashes.”

Londenvaarders

The area along the Singel canal from the Ronde Lutherse Kerk to the Lijnbaanssteeg is known as Londenvaarders. This part of the canal was where ships coming in from London would be docked. Anyone walking around this area during the 17th century would find English sailors and merchants everywhere they looked and it became a de facto embassy for Englishmen.

Singel 36

Look across the canal at #36 Singel. From this further away vantage point, you can really appreciate the elegance of the beautiful cornice in Louis XV style, which tops the house. In the centre of the richly decorated balustrade is this incredible carving of the god Mercury lounging, holding in his hand a large purse. Surrounding the relaxed god is a series of items relating to the trade industry like barrels, wine and animals. The house was originally built in 1763 for shipowner and trader Tamme IJsbrandsz Beth. Beth was troubled by the arrival of the British and the fact the London ships took over the area and wanted to create a powerful facade that would show his dominance over the British fleets.

Blauwburgwal

Continue along the Singel canal until you come to the Blauwburgwal canal on your left. The Blauwburgwal canal is the shortest waterway in the city center. It is sandwiched right between the Singel and the Herengracht by two scenic bridges. The trees which line either side of the little canal makes this such a picturesque little scene to stop in and look at.

De Dolphijn

Head back to the Single Canal and make your way down to #140. This is better known as the house De Dolphijn. The house was built in the 17th century for soap merchant Hendrick Laurensz Spieghel. The front facade consists of two identical stepped gables made of that iconic red brick with sandstone highlights. The house is one of the best examples of Dutch Baroque architecture in the style of Hendrick de Keyser.

The main characteristics of this style were the symmetrical facades created from brick using classical references. This can be seen with the addition of the images of Greek masks featured above the window pediments on the first floor. The house is one of the few facades in Amsterdam that still has scroll ornaments along the gables. Originally the house featured dolphins on both sides gable. The dolphin was the emblem of the Spieghel family, and therein is where the nickname of the house came from.

The Torensluis

As we continue down the Single Canal, we come up the enormous Torensluis bridge. This bridge is the oldest and widest bridge in the entire city, preserved since 1648. It measures a whopping 42 meters wide! The word “Torensluis” means “tower lock,” as the bridge was once home to a great tower that stood here until the mid-19th-century. Looking back at the bridge from further along the canal, study the area under the bridge along either side of the arches. There you can spot several small barred windows. Beneath the bridge, there was once a dungeon and prison cells connected to the old tower. Truly an example of how ingenious the architects of the city were. Using every little bit of space to cram in more infrastructure.

Multatuli Statue

Most of the bridge is now used by the cafes nearby as patio space. But amidst these seats is a statue of Dutch writer Multatuli. Eduard Douwes Dekker, better known by his pen name “Multatuli,” was a Dutch writer best known for his satirical novel Max Havelaar. This book was one of the first to denounced the abuses of colonialism in the Dutch East Indies. It is a considered piece of writing from 1860. Multatuli was truly a man ahead of his time as an anti-colonialist.

Singel 188

On the other side of the bridge at #188, we can find another great example of Amsterdam’s stone tablets. Most of the general public couldn’t read during the middle ages. Therefore to help businesses bring in customers, these stone tablets used pictorial images to depict their goods and services. This is a perfect example as the tablet above the doorway features a windmill. The house is named the “De Roo Oly Molen” or “The Red Oil Mill.” A few doors down at #194, you can find another example of a cobbler’s shop. This stone features a shoe and some cobbing equipment. Hundreds of years ago people would have just one shoe to their name and repairing their shoes was much more common than we do today. Early examples of sustainability.

Singel 192

The house at #192 features a beautiful neck gable with this curved pediment featuring a brightly painted bunch of grapes. The house was built in 1739 in Louis XIV style for the wine merchant Arend Roger. Just another example of how some merchants liked to advertise their businesses through their gable architecture. Something I genuinely wish we still did today, a great way to get to know your neighbours!

Singel 288

The gable along the top of the house at #288 features this wonderfully playful dolphin’s head. The dolphin appears to be bursting forth from the house with a spray of water cresting up behind him. Dolphins are a frequent symbol seen throughout Amsterdam, even though the canals are not home to these sea creatures. But the animals have a deep connection to the sailors and sailing merchants who would greet these great beasts on their voyages. Incorporating them into their home designs was a means of keeping that connection to the waters close to home.

Singel 326

The 18th-century house at #326 features the most incredible scene on either side of the beautiful neck gable. Sitting against the curved claw pieces are statues of Neptune and Mercury holding a golden trident and caduceus, respectively. Surrounding the lifting beams are also a swath of Acanthus leaves. Acanthus leaves are a symbol of enduring life. When combined with the images of Mercury, we can imagine that this house was perhaps a doctor’s residence.

Old Lutheran Church

The sizeable windowed building at #411 is the Old Lutheran Church. And when I say old, I mean old. It was built in 1632, that’s over 350 years ago! The church is a very, very odd one to visit. It is such an irregular shape. The floorplan curving to flank the edge of Spui road on the northern side of the building.

Singel 460

House #460 Singel is better known as the House Nürnberg or the Odeon building. It was designed by famed architect Philips Vingboons in 1661. However, previously, the lot had been used as a brewery as early as 1586. What makes this building stand out is the tall neck gable. The building is built in a rich, dark burgundy brick with contrasting light sandstone curved claw pieces decorated with elaborate festoons. Two oeil-de-boeuf windows stand below either side of the claw pieces. A large Cartouche surrounds the huge lifting hook. The festoons from the upper levels hang down below the windows. Looks like the building has been decorated for the holidays every day of the year!

Bloemenmarkt

Walking along Singel crossing the Koningsplein, we enter the great Bloemenmarkt. The Bloemenmarkt is the world’s only floating flower market founded in 1862. Back then, this part of the city was where flower growers would enter the canal to sell their plants. They travelled on large barges that floated beside the canal and buyers would simply hop on the barge. The barge would sit beside the streets and return to their ships once all the flowers were sold. Today the barges are affixed to the mainland. Sadly, much of the original flower market has disappeared over the years. Few to no vendors actually sell blooming flowers here. Instead, the market is mainly a tourist attraction with gift shops and souvenir stands. These focus primarily on tulip paraphernalia.

Tulip Bulbs

Some of the vendors do sell fresh tulip bulbs which you can bring home to plant. But only if your country allows them through customs (be sure to check!) Although it’s super touristy, I actually loved looking at the varieties of tulip bulbs for sale. It’s incredible to see how many different colours and even new “designer” flowers have been created. They were made by combining different strains of tulips together in the lab. If you can try to ignore the hoards of tourists and just focus on this, you might actually get something out of a visit to the Bloemenmarkt. But the Bloemenmarkt can get super crowded! You only need to see a portion of it to get the idea. I would advise jumping down Sint Jorisstraat and then walking along Reguliersdwarsstraat until you reach Vijzelstraat. This little back street is a great way to avoid the crowds.

Munttoren

Walking over Muntsluis bridge to find your way to the great Munttoren (Mint Tower), which sits at the intersection of the Amstel River and the Singel Canal. The great tower was initially located at the entrance to the city’s main gates along Amsterdam’s medieval wall. The original building was made in 1480 and consisted of two towers and a guardhouse. After the great fire of 1618, the tower was rebuilt as you see it today in Amsterdam Renaissance style. The entire structure was replaced in 1885 but maintains its medieval design.

In the 17th-century, during the Dutch wars against England and France, the city was occupied by these factions. The transportation of coins from their location outside the city was impossible with these restrictions. So the guardhouse was set up as a temporary mint, giving the tower its official nickname. The building features a beautiful tower design by Hendrick de Keyser. They installed a clock face on every side of the spire so that citizens on every corner of town could look to it to tell the time.

The Dancing Houses

Make a quick detour over the Halvemaansbrug and onto ‘s-Gravelandseveer street. From here you have the best vantage point over to the famous Amsterdam Dancing Houses. Since houses in Amsterdam were built upon muddy marshland and stand on old pine-wood poles, some of the houses have begun to shift and sink over time. Surprisingly it’s not the weight of the house that creates the unevenness, but the water level. So long as the pole remains under the water, its integrity is preserved. But the second the water level drops, the wood can start to rot. The rot weakens the structure and causes this sagging effect. Although many houses are sinking, this row of houses seems to be suffering the most. They have become affectionately known as the “dancing queens” or “dancing houses.” The wobbling levels making them appear as though they are dancing up and down.

Grimburgwal

Just around the corner from the Dancing Houses is the Grimburgwal. This canal marks the outskirts of the Red Light District. The Grimburgwal also marks the entrance to the Medieval centre of Amsterdam. This narrow watery passageway connects the great Oudezijds Voorburgwal to the Amstel river via the Rokin canal. The name “Grimburgwal” comes from the word “grim,” which means “muddy ditch” and “burgwal” which means earthen wall. This part of the city was home to this large earthen wall dug out along the muddy waters used to protect the medieval city. The wall was destroyed in 1384 during the city’s expansion. The Grimburgwal remained the city’s southern canal border until 1425 when the canal belt began to be constructed. It’s a small, almost forgettable canal today, but its rich history is something to take note of.

The view from the Amstel River along the medieval Groenburgwal, with the steeple of the Southern Church in the background, has been painted by several famous painters over the years. Rembrandt himself would come here to paint as the canal was so close to his home. But the most famous painting of the canal was made in the 19th-century by impressionist painter Monet.

Kloveniersburgwal

From Grimburgwal walk back towards the Aluminium Bridge, which crosses over the Kloveniersburgwal. The Kloveniersburgwal canal was dug out in the 15h-century originally designed as a defensive canal to protect the Oudeschanst. The canal’s name comes from the division of the civic guards called the ‘kloveniers‘ who worked along with these defences.

During the Second World War, Kloveniersburgwal was the border of the Jewish quarter. It was here that the Germans started to segregate the Jewish population of Amsterdam before sending most of them off to concentration camps. At one point, more than 25,000 Jewish people were living here. Sadly, 75-80% of the people from the neighbourhood were deported and murdered by the Nazis. After the war, this part of town must have been hauntingly empty, a constant memory of the loss.

Oudezijds Voorburgwal

Walk west along Vendelstraat, through the pedestrian walkway north towards the Sleutelbrug, which looks out over the entrance to the Oudezijds Voorburgwal. The Oudezijds Voorburgwal (often abbreviated to OZ Voorburgwal) means “old city walls.” This area was where the defensive ramparts continued around the old medieval city. The canal was originally nothing more than a little creek but was dug out to create this large waterway in the 14th century. As the canal was one of the first large expansions, it is where we can find some of the oldest buildings in Amsterdam.

Red Light District

During the Dutch Golden Age, the canal was a hub for commerce and ships coming into port. This influx of sailors led to the development of what we now call the “Red Light District.” While some people only come here to gawk at the red light dancing girls, there is so much more to this historic canal to see and appreciate.

Despite the fact that today the area is known for its illicit activities, in the middle ages, the canal was where you could find a large number of monasteries, churches and religious institutions. During the 17th century, many wealthy Catholic merchants made this part of the city their home. Back then, the area was nicknamed the “Velvet defence-canal“. Sort of a dig at the rich merchants who lived here who were known for dressing in fancy velvet clothing.

House at the Three Canals

At the intersection of the Oudezijds, the Achterburgwal and the Grimburgwal, we find the Huis Aan De Drie Grachten or House on the Three Canals. Name because it is located at this meeting point of these three famous waterways. This house is so fantastical, designed in high Dutch Renaissance style. I especially love the large leaded glass window and set-in brick arches above them. The charming red wooden shutters making it so classical Dutch looking. The house was originally two separate lots built around 1610!

The house was designed for bricklayer Claes Adriaensz van Delft. Seeing as it was made for a bricklayer it is only appropriate that the bricks on this house are among the most impressive parts of the entire building. During the 1930s, a bookstore was opened in the house. Inside, the various bookshelves hid behind them, secret compartments where Jewish people on the run from the Germans could hide. These hidden compartments were only discovered in 2005 during renovations to the building. Adding to the already illustrious history of the building.

Agnietenkapel

Behind this grand arched entrance, is the doorway into the old Agnietenkapel, also known as the Chapel of the Convent of Saint Agnes. This is one of the oldest structures in the city, dating back to 1470. In the 15th century, the area along the southern half of Oudezijds Voorburgwal canal was called the stille zijde or the “quiet side.” This so-called peaceful part of town became popular with religious institutions looking for a monastic place to build their home. Away from the hustle and bustle of the raucous trade center. Very ironic today that all these churches are now located in what would be considered the most unholy neighbourhoods, the Red Light District.

Athenaeum Illustre

In 1578, when the Catholic city government was deposed in favour of the Protestant one, all Catholic churches and monasteries were demolished. This was called the Alteratie, or the “alternative.” But the Agnietenkapel was thought to be too beautiful to be destroyed. Instead, in 1631 it was converted into the Athenaeum Illustre. The Athenaeum Illustre, or Amsterdamse Atheneum, was a city-sponsored ‘illustrious school.’ An Athenaeum Illustre was neither a university nor just a school. It fell somewhere between where it would teach at an academic level, but there were no degrees given out. In the 17th century, each province was only allowed one official university, and Holland already had a university at Leiden. It wasn’t until 1815 that it was recognized as an official academic institution where diplomas could be given out. Leading to its transformation into the University of Amsterdam.

Church Gate

The Agnietenpoort or Church Gate is fantastically carved with so many ornaments placed along the archway. You can see why they decided to preserve it when it changed hands from the church. On the top, set into a large shield is the Amsterdam coat of arms. The coat of arms of Amsterdam consists of a red shield (here just plain stone) with three silver Saint Andrew’s Crosses down the middle highlighted by a black pale. The black pale symbolizes the Amstel River, while the three crosses represent the three dangers of Old Amsterdam: fire, floods and the Black Death. St. Andrew is the patron saint of Amsterdam as he is the patron saint of fisherman as the city was originally just a small fishing village.

Surrounding the coat of arms is typical Vredeman de Vries motifs. Hans Vredeman de Vries was a Dutch Renaissance architect best known for his publication in 1583 on garden designs. Inside this book were many drawings of floral ornamentations that have since been referenced ever since on buildings all over the city. A large cartouche frames the emblem with the year 1631 below and a roaring lion on top. The Dutch Republic Lion was the badge of the Union of Utrecht and a precursor of the current coat of arms of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. You’ll find lion symbols all over the city to represent this ancient heraldry.

Amsterdam Municipal Pawnshop

Pawnshops have truly been around forever! Proof positive of this fact is the old Municipal Pawnshop found along the canal. This building was established in Amsterdam in 1616. It was created as a municipal charity to protect poor people from shady loan sharks. These loan sharks would lend out money at a sky-high interest rate that made it impossible to ever pay back and get out of debt. The Amsterdam Municipal Pawnshop, or Stadsbank van Lening, was started as a not-for-profit city bank that still operates today! It is considered the oldest bank in Amsterdam and one of the oldest banks in the world!

Above the doorway, you’ll find the city coat of arms topped by the Emperor’s crown. In gold lettering, along the pediment over the doorway, is a poem in Dutch. It reads, “Have you neither money nor property, pass this door. Have you the last, and do you miss the first, come to me. Give pledge, I give you money, why should I guarantee you? Or isn’t it enough that you live off mine? But if you return your pledge, you must take care in time. That my principal will return with interest. I help you and me and show it to the investigators. Of my secrets, the grave of forgotten usurers.“

The Prinsenhof

Another holy institution located along the Oudezijds Voorburgwal was the St. Cecilia Monastery. The original church was built in the early 15th century but after the Alteratie, the Catholic institution was converted into the city’s Prinsenhof in 1581. It was named the ‘Prinsenhof‘ after Prince William of Orange. In the late 16th century, the prince of Orange was the ruler of the Netherlands and would often use the building as his primary residence. It was later used as the Admiralty in the 17th century.

Prinsenhof as City Hall

In 1808 King Louis Bonaparte pulled the old switcharoo and wanted to convert the beautiful Dam City Hall into his Royal Palace. This meant the city needed to find a new location for its city hall. Seeing as the Prinsenhof was little used at this time, it was selected as their new City Hall. The building was used as accommodation for visiting dignitaries, mayors and, of course, city council meetings. When the city council moved in, the building saw a huge change in the architecture to suit its new function.

Amsterdam School Style

The new style of architecture which came out of the building of the new city hall was called, “Amsterdam School Style.” Like all variations of Dutch architecture, it heavily featured brickwork. The use of bricks is the primary building material in Amsterdam is due to the fact that the city’s access to clay. Clay is found in abundance around the rivers which encircle the city. Amsterdam School structures are also characterized by a rounded appearance, as demonstrated here by the curved facade bowing out towards the canal. The style also tended to favour decorative masonry, wrought iron accents, spires and ‘ladder’ windows. The style is slightly reminiscent of the Art Deco design aesthetic but with a Dutch interpretation. The decorative masonry here features large artistic pillars along the first floor. They depict men and women as symbols correlating to administrative virtues such as simplicity, courage, and diligence.

City Hall Public Urinal

Across from Oudezijds Voorburgwal #195 is a small brick and stone cylindrical structure which is actually a public urinal! A urinal probably seems like a very strange thing to make a point to visit. But this urinal has become an actual National Monument. It was built in 1926 and renovated for the new City hall. The urinal was designed to fit into the same uniform Amsterdam school style as the City Hall. Right on top of the urinal entrance, you’ll find another sculpture designed by artist Hildo Krop. This sculpture matches the same sculptures on the pillars outside the City Hall. If nature calls, men can still use the rudimentary bathroom today!

Oudezijds Voorburgwal 187

The Dutch Classical black brick building at #187 has a very interesting gable design, specifically around the ornate claw pieces. The house was built in 1663 for an American tobacco trader. We can tell the house was designed for a merchant working in the Americas because of the imagery featured in the claw pieces. We can see sculptures of the merchant’s enslaved Africans holding tobacco leaves. Above them are pictured personifications of indigenous workers carrying large harvest baskets.

Amsterdam’s Architecture of Colonial Exploitation

Many parallels can be drawn between America’s colonization and the enslavement of the African people to the Netherlands’ own dark colonial past. Everyone knows that the “Dutch Golden Age” was the city’s great boom in the 17th century brought about by its free and tolerant society and its enormous trading empire. With the creation of the Dutch East India Company, the Netherlands had an empire of ships that roamed the coastlines of Asia and Africa.

But it wasn’t just spice and silks they brought home. They also colonized countries and robbed them of their natural resources. And although the Dutch didn’t bring slaves back to their home country, the colonies suffered through a period of around 200 years of slavery until it was abolished in 1863. While houses like this and other images of slavery are tough to observe, it’s essential to understand and accept this period of Amsterdam’s history. You can learn a lot more about Amsterdam’s Architecture of Colonial Exploitation in this great article!

Oudezijds Voorburgwal 136

The house on Oudezijds Voorburgwal #136 was first built in the 16th century. Above the doorway, there is an iconic wooden relief featuring the famous navy officer Admiral Cornelis Tromp. Cornelis Maartenszoon Tromp lived in Amsterdam but never at this particular residence. In fact, the relief wasn’t installed until well after his death. The house was purchased by trader Jan Pranger who had a great reverence for Cornelis Tromp as a fellow sea traveller.

Admiral Cornelis Tromp Stone Tablet

Tromp can be seen in his heroic pose, his hand resting on a large globe above a scrolled nautical chart in the background. The relief was hidden for years when the house was converted into a printing shop that covered up the old plaque. In the 1990s, when the house was being refurbished, the old emblem was released, and they went about restoring the brightly painted colours to their former glory. The house basement was converted into a sex shop in 1980 but today the house serves as the headquarters for the green energy initiative in Amsterdam.

Bulldog Coffeeshop

The Bulldog Coffeeshop is a famous landmark in the neighbourhood as it is the oldest “coffee shop” in Amsterdam. It was established in 1974 as a secret “speakeasy” for soft drugs. Despite multiple raids over the years, eventually, the city began to tolerate the sale of these drugs. Many people think marijuana is legal in Amsterdam, and surprisingly that’s not the case. But it is generally accepted, even by the police, who look the other way. The original location is worth visiting as you can discover more about the history of cannabis in Amsterdam inside.

Even if you don’t partake in the consumption, you can’t visit Amsterdam without seeing what these “coffee shops” are all about. Plus, this location has a full menu with food and drink options that don’t contain any drugs. I myself don’t partake but still had a blast checking them out and seeing what a comfortable, friendly atmosphere I was greeted with inside.

The Oude Kerk

The crowing glory of the Oudezijds Voorburgwal canal is the grand Oude Kerk. The Oude Kerk or “Old Church” is named as such because is the oldest religious institution in the city. The first wooden part of the structure was constructed here in 1213! Originally the church was named St. Nicolas Church after the patron saint of the city.

The area they selected for the church was a sold mound in the otherwise marshy settlement. This allowed the church to grow in size without requiring much additional foundation work. Today the church sprawls out over 36,000 sq ft. Each generation of Amsterdam’s religious elite seemed to have added their own personal touch in its expansion. In the 14th century, the side aisle was lengthened, and the great medieval wooden vaults were installed. These remain to this day are the oldest medieval wooden vault in all of Europe. The vaults were made out of great Estonian oak planks. Some of the plants were stained in various colours to look like paintings on the ceiling. Bands of florals surround each part of the vault with golden stars decorating the keystones. These vaults are still thought to provide some of the best acoustics even amongst the more modern churches.

Miracle of Amsterdam

In the 14th century, the church was the site of the “Miracle of Amsterdam.” One day, a dying man accepted the sacramental bread during communion. But after ingesting it, he began to vomit it up in a fit of pain. When the priests threw the vomit into the fire, the bread did not burn, and the act was proclaimed a miracle. Even stranger than the miracle itself was the fact that the vomitted bread was preserved in a relic chest and kept inside the church. Sadly their miracle relic was one of the many items which disappeared during the Alterie.

Stained Glass

In the 15th century, a north and south transept were added to change the floorplan of the church into a cross shape. The beautiful large windows inside the church were installed in 1406 and were once covered in vibrant stained glass. More and more windows were added over the years, totalling 33 large-scale artfully made scenes. Sadly during the great fire of 1536 and the gunpowder explosion in 1654, all of these original windows were destroyed.

Most of the windows are now plain glass replacements but, beginning in the 20th century, these windows began to be restored. Using paintings, drawings and historical architectural plans, the church museum started to create modern interpretations of the ancient windows. There were created by artist Joep Nicolas. The windows depict various biblical stories, such as the Parable of the Prodigal Son and the story of baby Moses. But they also commissioned some modern, secular scenes as well. Inside the Memorial window are depictions of WWII victims who were killed during the Nazi occupation. The Libration window also commemorates the Netherlands’ liberation from the German and Japanese occupiers.

Oude Kerk & the Alterie

After the Catholic Reformation in Amsterdam during the late 16th century, the church was looted and defaced on multiple occasions. This stripped the church of much of its original decorations save for a few paintings. The thieves couldn’t reach them as they were installed high up under the vaults. After the Reformation, the church was used as a meeting house for the public. People would come here to escape the cold and the rain to gossip, sell their goods, and it was even used as a de-facto homeless shelter.

In the 17th century, the church was reconsecrated and been given a fresh coat of paint. New decorations were installed, including a new oak screen which referred to the desecration during Reformation. It states, “The prolonged misuse of God’s church, was here undone again in the year seventy-eight.”

Rembrandt & Oude Kerk

One of the most famous Dutch painters, Rembrandt himself, was a frequent visitor to the Oude Kerk. All of his children were baptized inside the temple, and it is one of the few original buildings left in Amsterdam where the painter roamed the halls. His wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh was buried here in 1642 inside the Holy Sepulchre. Another famous figure buried is naval hero Jacob van Heemskerck who was a central figure in Rembrandt’s masterpiece The Night Watch.

Today, the church is used as a contemporary art gallery where the ancient architecture is the backdrop for modern art. Entry into the church costs €12 for adults and €7 for students; children under 13 are free. On Sunday mornings, the church still opens its doors for worshippers for free but only for those serious about coming in to pray.

Oudezijds Voorburgwal 57

Across the bridge from the Oude Kerk at #57 is a gorgeous example of Amsterdam Renaissance architecture made by the famous architect Hendrick de Keyser. They call the house the De Gecroonde Raep. It features one of the finest examples of stepped gables in Amsterdam. With these gorgeous scalloped stone carvings above each step. The facade also features these beautiful brace arches above the windows with smallmasks set into the pediments. Iconic features of Keyser are the double pilasters with cartouches set in between the brick pillars.

Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic Museum)

Hidden behind an otherwise simple brick facade is an example of a “schiller” or “clandestine church.” After the Reformation, Catholics needed to practise their religion undercover. A few old houses on the canal were converted into these secret churches. This church went by the name Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic Museum). It was built by a Catholic merchant in 1663 who transformed his third-floor attic space into the beautiful yet cramped religious wonderland you find today. Personally, I adore the pink-painted balustrades and railings, such a unique touch.

Visiting the Museum

After Catholics could practice in public once more, the church was exposed and opened as a museum in 1888. This makes it the second oldest museum in Amsterdam. Today, it remains a museum visited by over 85,000 people annually. In addition to viewing the secret church, you can also tour the 17th-century merchant canal house interior. Tickets are €14 for adults and €7 for children and students.

Oudezijds Voorburgwal 18

House at #18 bears a striking (if not a simplified version) of the house saw a few doors down at #57. The curved arches above double pilasters are a clear sign of the work of Hendrick de Keyser. Above the third floor, there are face masks, but on the lower levels, we find lion masks. Above the stone gable is a relief depicting the legendary castle of Egmond aan den Hoef.

Oudezijds Voorburgwal 14