The ‘Slav Epic‘ is one of the greatest works by Czech artist Alphonse Mucha. Over 20 years, Mucha painted 20 enormous canvases, some measuring over eight meters tall! He called this series the ‘Slav Epic’ as it explored the history of the Slavic people.

If you’ve visited Prague, there is no doubt you will have come across Mucha’s work. He is one of the most prolific Czech painters in the world, and the city LOVES his paintings and posters. They seem to appear on every street corner and postcard in Prague. His famous prints have become so popular they are often sold at University Poster fairs and cover the walls of hundreds of dorm rooms around the world.

Mucha’s Art Nouveau

His style of art is quintessentially Art Nouveau. Most of his more commercial works feature images of beautiful young women in flowing dresses surrounded by lush flowers. He kept the tones for these advertorial pieces in pale pastels, typical of the art nouveau style. But the ‘Slav Epic’ is something completely different. A departure from his commercial work and something genuinely personal to the artist. If you are interested in learning more about the Slavic people and their history, this is an immersive and exciting way to do it!

Where to Find the Artwork

I am SO EXCITED to finally get to update this blog with the new locations for the Slav Epic. When I visited Prague in 2015, I didn’t know I would be one of the last people to see the Slav Epic in person. I caught the exhibition just a few months before it closed. Until the end of 2016, the Slav Epic was housed in the National Gallery’s Veletržní Palace in Prague.

Moravský Krumlov

Originally, the canvases were exhibited in the city of Moravský Krumlov. They were displayed in the castle and remained a precious treasure of the town for over 50 years. Then, the city of Prague contested that the painting had been left to them by Mucha in the first place. And they shouldn’t be displayed so far away from where most tourists visit. But Prague had no space suitable for showing all these incredibly large works of art. You almost need an airport hanger! The city of Moravský Krumlov felt the paintings needed an appropriately regal and elevated space. They wanted them to be displayed inside the old palace of Moravský Krumlov, where they felt like they belonged.

Political Battle over the Paintings

In 2012, the city of Prague eventually won the right to display the works. They found a temporary space for them in the National Gallery’s Veletržní Palace. But this space was only to house them for four years. After 2016, the paintings were boxed up, and a political battle between Prague and Moravský Krumlov erupted again. No one could agree on where they would be displayed. They travelled to Japan for international exhibitions, but when they returned, they sat in storage.

Finally, in 2020 the Prague City Council decided to return the paintings to the château in Moravský Krumlov. They will be on display here until 2026. After returning to their original home, the canvas exhibition spaces were repaired to better showcase these incredible works of art.

Access & Admission

As the exhibition takes place in Moravský Krumlov, most visitors will arrive via Prague, Vienna or nearby Brno.

The train from Prague to Moravský Krumlov takes about 4 hours (with one transfer.) After arriving at the stations, you can hop on a bus which will take you to the entrance to the castle. If you are travelling from Vienna, the journey is slightly shorter, only 3 hours on the train. The shortest trip will be from Brno, as it is only 1 hour on the train.

Tickets

It’s best to purchase tickets in advance to ensure you won’t be disappointed that they are sold out when you arrive.

Prices: Adults 250 CZK, Seniors 65+ 170 CZK, Students 10-25 years old 150 CZK

Hours

January–May: 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. (last entry at 3 p.m.)

June–August: 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. (last entry at 4 p.m.)

September–December 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. (last entry at 3 p.m.)

all year round: closed on Mondays

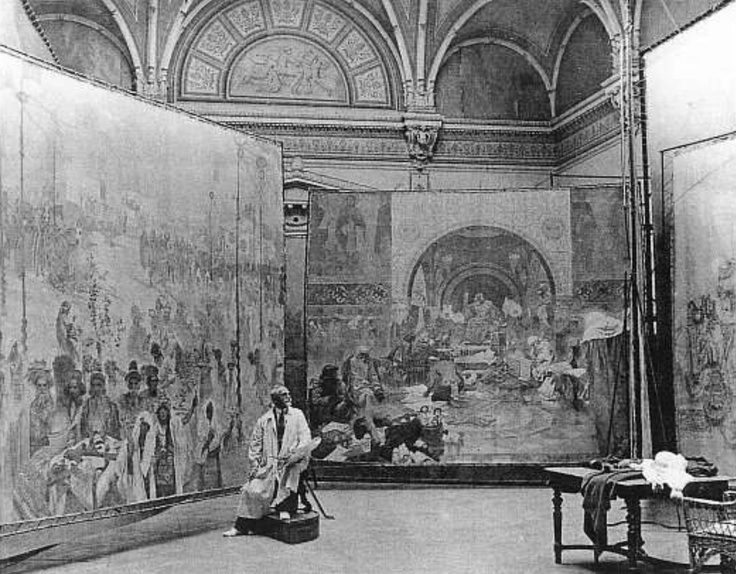

The Size Paintings

Seeing the paintings for the first time in person, you’re immediately awestruck by the sheer size of these canvases. They feel more like walled frescos than simple pictures. Moments are frozen in time, captured in life-sized (and in some cases, larger than life) works of art. Each of the paintings depicts the history of the Slav people, their civilization, wars, and celebrations. The next thing you’ll notice about these paintings is how the people represented differ from Mucha’s other works. These are not the languid, sensual forms of Mucha’s commercial art nouveau posters. These deftly painted scenes profoundly portray the emotions and collective journey of the subjects in each brushstroke.

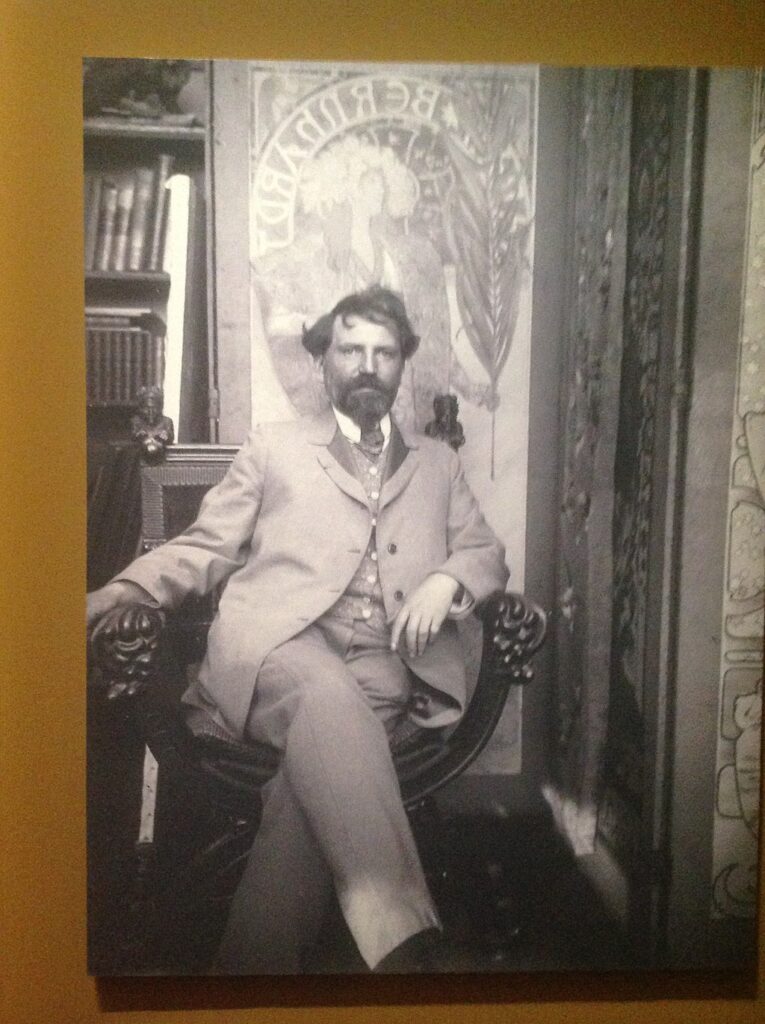

About Alphonse Mucha

Alfons Maria Mucha, although better known internationally as Alphonse Mucha, was a Czech painter born in 1860. He born in the small town of Ivančice in southern Moravia. Mucha showed an aptitude for painting very early on. He received his secondary education at the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul in Brno. He was accepted into the arts school firstly as he was also an accomplished singer. Mucha was famously quoted as saying, “for me, the notions of painting, going to church, and music are so closely knit that often I cannot decide whether I like church for its music or music for its place in the mystery which it accompanies.” The dramatic scenes in many religious paintings undoubtedly influenced the art he would later go on to make.

Mucha in Vienna

At 19 years of age, Mucha travelled to Vienna. There he became an apprentice scenery painter for theatre companies. His flair for the dramatic would continue to be influenced through these explorations. After his apprenticeship, Mucha moved back to Moravia. There he was employed by Count Belize to create portraits, decorative art and lettering for tombstones. Belasi saw Mucha had real talent. He wasn’t just an everyday artist. Belasi brought Mucha with him on his trips to Venice, Florence and Milan. There he was able to introduce him to many more professional artists.

Mucha in Paris

Eventually, Mucha moved to Paris in 1888 and started to professionally study art at the Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi. These schools specialized in studying female nudes and figurative paintings. As well as historical and religious art.

While in Paris, Mucha lived inside the Slavic community boarding houses who famously sheltered struggling artists. It was perhaps living within this community that endowed Mucha to the Slavic people even more. Mucha’s first large client was the Central Library of Fine Arts. It was from here that his career as an illustrator and graphic artist took off. He successfully made a life for himself in Paris for many years, creating commercial art. These printed works featured his iconic attractive sets of women, in flowing gowns and floral backdrops.

History of the Slav Epic

At the age of 43, Mucha returned to his homeland of Moravia. There, he devoted himself to painting a series about the history of all the Slavic people. Mucha’s inspiration for the series first started when he was researching another assignment. While studying and travelling through the Balkans, he was genuinely struck by the hardships and sufferings of the Slav people. He also noted there was no real documentation of these people’s stories in art. Mucha decided it would be his final task to bring these stories to life with paint.

Although he secured a financier for the giant undertaking, this was more of a passion project for the artist. Sitting in his studio, surrounded by this enormous canvas, Mucha painted the past into reality. The Slav Epic depicts in chronological order the mythologies and histories of the Czechs and Slavic people.

Romanticism

Many of the themes in this series fall under romanticism. Romanticism is characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism and the glorification of the past and nature. In these paintings, sensations are portrayed on people’s faces in a far more sophisticated way than before. Looks of horror, terror, awe and apprehension started to round out the range of human emotion in art. Previously emotion had been stunted between pure joy or sadness. Romanticism also elevated folk art, which had previously been thought of as a lesser form of art.

It took Mucha over 14 years to complete the series. In 1928, on the 10th anniversary of Czechoslovakia’s independence, Mucha presented the collection of paintings to the Czech nation. He considered it his most important piece of work he ever created. The Czech Republic cherished the gift. It was like nothing else they had ever seen before. Notably, during World War II, the Slav Epic was one of the first things hidden away before the Nazis took hold of the city and seized works of art.

The Slavs in Their Original Homeland

The series is set chronological and starts with the painting entitled “The Slavs in their Original Homeland,” painted in 1912. In the 4th to 6th century, the Slavic people lived largely in unpopulated, rural areas, which often were considered marshes. Because there was no national army to protect these farmers, their lands were invaded time and time again.

In this painting, you can see a mother and child hiding in the bushes. Behind them, their village is being burned to the ground. The red fires glowing in the distance to the left of the frame. Their eyes are so vulnerable and seem to cry out to the viewer for help. They look right into your soul. This is a trope that Mucha uses throughout almost the entirety of the series.

In the top corner of the piece, you can see three figures floating in mid-air. The largest of the figures, a priest, holds his hands outstretched. In the same position as Jesus on the cross. The two on either side of him are a young boy and girl. The boy, dressed in blood-red robes represents war. The girl on the right, dressed in white represents peace. The two figures seem to foreshadow the future of the Slavic people. Their history is marred by many wars but also by the hope for peace.

Colours in the Slav Epic

The colours used in this painting are significant in the series and also in comparison to Mucha’s other works. Most of Mucha’s artworks are pale and delicate. In this series, we find there is definitely a dark tone to his work. Colours here are not just used haphazardly. He uses colour to his advantage and to help tell the story using symbolism.

Many of the paintings throughout the series have two separate planes of existence set in the same scene. Often mythological beings are seen floating above the historic action below. This is Mucha’s way of combining the essential mythologies of the Slavic people to past events.

The Celebration of Svantovít

Sventovit is a Slavic deity of war, fertility and abundance. Sventovit is depicted as a four-headed god with two heads looking forward and two looking back. These four directions are positioned like a compass, looking north, south, east and west. The different directions they point also symbolize the different seasons of the year. Mucha’s next piece, “The Celebration of Svantovít” features the god Sventovit is located in the upper right portion of the painting. The god’s head is just cut off on the top of the canvas. Almost as if we portals cannot look upon him. But we can see some of the branches which sprout forth from his head. He is surrounded by other celestial beings painted in an almost opalescent quality.

Arcona

Before the 1200s, the Slavs headed westwards and built a temple to Sventovit in the city of Arcona. As Sventovit was also the god of the seasons the Slavs would have a grand celebration every year during the autumn. The festival was obviously held at this temple. Pilgrims would come from all over Europe to celebrate with them here.

In 1168 the Danes attacked the city and destroyed the temple in their conquest of the east. We can see the Danes in the upper left corner of the canvas. They are represented by the fearsome-looking warriors being lead by a pack of wolves.

Celebration

Below the celestial scene, the Slavs are preparing for their autumnal celebrations. The Slavs and pilgrims are all dressed in white, a symbol of purity. Only one character seems to be aware of the incoming attack. A mother holding her child in the center of the frame looks out at the viewer. She is almost begging the viewer to take notice. And save them from the horrors which are about to happen to the peaceful pilgrims and Slavs.

Introduction of the Slavonic Liturgy in Great Moravia

In this painting, the “Introduction of the Slavonic Liturgy in Great Moravia” we have a lot going on. So let’s study the earthly plane first. The scene takes place in Velehrad around the year 880. In the lower right corner of the painting, we see a ray of light shining down. A deacon, with his back turned to the audience, reads out an edict. Sitting on his throne awaiting the reading is Prince Svatopluk of Greater Moravia. The deacon is reading out the announcement that Pope John VIII has officially sanctioned the use of Slavic liturgy.

To the left of the deacon, almost hidden behind a small tree, stands Methodius. Two novices are seen kneeling by his side. The task of translating the Bible into the Slavic language was a job upon which Methodius staked his life. And it would make him a saint. Methodius, and his brother Cyril, both helped with this translation of the Bible. The Pope also made Methodius archbishop for his achievements. In the middle ages, having a bible in your native language was a way of ensuring its legacy.

Slavic Language

But not everyone is happy to hear this news. The two German priests surrounding Svatopluk, whose faces are shaded and almost hidden in darkness, can barely conceal their anger. These Germans had been making their way through Moravia in the hopes of eliminating the Slavic language for good. They wanted to force the Slavs to learn the German language in order to practice Christianity.

In the very front of the foreground, once more staring out at the audience, stands a young man with his fist clenched. He raises his other hand in the air, which holds a large ring. The circle symbolizes this moment of strength in unity for the Slavic people.

Boris of Bulgaria and Igor of Russia

Floating above this scene, we have members of the divine realm. In the upper left corner, we can see the Pope sitting on his throne. Beside him, sits the Byzantine emperor, who was the head of the Orthodox Church. Surrounding the great religious leaders Slav who suffered forced Germanification, who now cry out for comfort. In the center of the ethereal world, we see stylized images of Methodius and Cyril as Saints. To the very right, we have the portraits of Boris of Bulgaria and Igor of Russia and their wives. These rulers helped spread the Slavic Bible across the country which helped strengthen their rule and their culture.

Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria

Much as the Bible was important in the perpetuation of the Slavic language, art and literature were also significant in ensuring a legacy for this nation. When Methodius died, the Archbishop of Moravia, Prince Svatopluk, under the influence of his German priests, withdrew his support for the Slavic Bible. With this exodus, he also exiled all of Methodius’ followers out of Moravia. They were scholars without a place to call home. Methodius had died and his successor was not recognized by the Pope and therefore had no power. His followers felt they were the only ones left who could continue Methodius’ great work. But all was not yet lost.

Tsar Simeon I

Luckily, Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria, who had a great kindness in his heart for the Slavic people, gave the scholar refuge inside his court. Tsar Simeon I, was a powerful ruler. Simeon’s successful campaigns against the Byzantines, Magyars and Serbs led Bulgaria to its greatest territorial expansion ever! It was on its way to being one of the most powerful states in Eastern and Southeast Europe. But Simone was also a lover of literature and art. We can see Simeon himself highlighted here under a golden arch. He is seen dictating to his scribes from his raised dais. Other scholars are spread out all over the court. Almost hastily and messily, writing and reading under the golden light of the throne room.

The painting’s foreground is rather small. The upper portion, which takes up about half the space, focuses on the palace’s decor. The frescoes on the wall feature both Byzantine and Slavic designs. Slavic leaders are painted, and a circular motif is applied in gold to the front of the baldachin.

King Přemysl Otakar II of Bohemia

The fifth painting in the series is entitled “King Přemysl Otakar II of Bohemia.” This painting was made 12 years after the first. The piece depicts King Přemysl Otakar II, who ruled Bohemia from 1253-1278. The King is celebrating the marriage of his niece to the prince of Hungary. This marriage would forge a great alliance and strengthen the bonds of both countries.

The wedding took place on October 5th, 1264. It was one of the greatest celebrations in Europe’s history to date. Held on the banks of the Danube, under a large canopy, fancy tents were set up along the river to accommodate all the royal guests. The event was dubbed the “Union of Slavic dynasty“. The King happily is greeting his guests inside an ornate tent covered in rich carpets and a beautiful mosaic dome. This scene is lit from above, as if from that celestial place. The light of the hope for the countries’ futures.

The Coronation of Serbian Tsar Štěpán Dušan

The next painting in the series is the “The The Coronation of Serbian Tsar Štěpán Dušan.” Dušan fought many successful wars, growing the size of the country and enriching the livelihood of his people in the process. On Easter Sunday in 1346, he had himself crowned as the Tsar of the Serbs and Greeks. The painting takes place on the hillside, down from the Church of Saint Marko near Skopje. In this scene, we see crowds of peasants and nobles alike, in line for his coronation. Under Dušan’s rule, Serbia was the major power in the Balkans, and a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual empire. He enacted Dušan’s Code which was a compilation of several legal systems, which is considered to be one of the first acts of the constitution.

The children will follow in their leader’s footsteps and bring freedom to the Czech people

Dušan is depicted at the centre of the frame, but not larger than any other person presented. Walking in front of him are some young Serbian girls in traditional attire. The children stand at the front of the procession, as Mucha always maintained that “the children will follow in their leader’s footsteps and bring freedom to the Czech people.” In their hands, they carry flowers and olive branches, the symbols of peace and victory. The children’s gaze focuses once more on the viewer, asking them to join in on the celebrations.

Jan Milíč of Kroměříž

This painting, “Jan Milíč of Kroměříž,” is the first of a triptych in the Slav Epic series. These three paintings jump forward in history slightly and focus on the reformist preachers of the 14th and 15th centuries. Jan Milíč of Kroměříž was a Czech Catholic priest who found himself in opposition with the rest of his clergymen. He found the Catholics to be immoral and indulgent. Their greed was outweighing their piety.

He redesigned from his official priestly duties and instead dedicated himself to helping the sick and poor of the city of Prague. Milíč made it his mission to persuade the prostitutes of a large house of ill repute to shed their sinful ways and repent. By the sheer eloquence of his words alone, they followed.

Unlike the rest of the paintings in this series, this one is primarily made up of women. Even Milíč himself is very small in proportion to the rest of the scene. At this moment in time, we can see the former prostitutes shedding their brightly coloured clothes and lavish jewels in exchange for simple, white robes. A mode of dressings that represented their newfound purity.

Jerusalem

Milíč set about building a new church, which he would call his “Jerusalem“. This church would become the Týn Church which now stands in Prague’s Old Town Square. In this painting, we can see the women gathered around the spot that would become this church. The scaffolding reaching high up, making the verticality of the painting one of the most impactful things about this piece. One of the prostitutes in the foreground, dressed in red, has her mouth gagged in order to prevent her from gossiping, a mortal sin.

Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem Chapel

The second and largest painting in the triptych is “Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem Chapel”. In this dimly lit scene, we see the Czech theologian and philosopher Jan Hus sitting in the center of the Bethlehem Chapel in 1412. Jan was at the height of his popularity at this time. Jan Hus preached against the Catholic Church of Bohemia, as he believed they were using the church for their own gains. And they would not let the Bohemian people have the Slavic language used in church. The scenes show Hus on the left side of the painting, preaching from his pulpit. But Hus, despite being perhaps the most famous character in the scene is not the central focus. The audience is filled with both everyday people and the highest rungs of Bohemia. All together, presented equally.

The church is also filled with famous characters who would shape the future of Bohemia. Perhaps influenced by the teachings of Hus. The future leader of the Hussite army Jan Žižka, stands under a fresco of St. George and the Dragon. In front of the pulpit is a small group of Hus’ students who are diligently taking notes. All of them sit there, transfixed by the words he speaks.

Queen Sophia, wife of King Váklav IV

On the right side of the frame, we see the bright red canopy of Queen Sophia, wife of King Váklav IV. She sits with her assembly listening to the great lecturer. One of her ladies in waiting turns her head to the side, looking off at a shadowy figure in the corner. This figure represents one of the spying priests who would bring about the death of Jan Hus.

Mucha represents the Bethlehem Chapel as he imagined it. The real church was destroyed in 1836, long before Mucha started this painting. Mucha draws the interior in the high Gothic style as it feels so grand and perhaps reflects the magnificence of the sermons Jan Hus would have been giving. You can visit the new Bethlehem Chapel in Prague today, and while the architecture isn’t nearly as impressive now, its prominence in history is unparalleled.

The Gathering at Křížky

Jan Hus’ teachings were not taken kindly by the papacy. When Alexander V was elected as a pope, he excommunicated Hus. But this would not stop him from preaching. Angered at his insolence, the pope plotted to arrest Hus. He planned an assembly of the Council of Constance to discuss Hus’ opposition to the church. When Hus arrived to have what he thought would be a sensible debate, he was arrested. They repeatedly ask Hus to stop preaching and bend to the ways of the Catholic church but Hus just repeated, “I would not for a chapel of gold retreat from the truth!”.

Hus was burned at the stake for “heresy against the doctrines of the Catholic Church“. As he burned they say he could be heard singing Psalms, a peaceful protestor to the end. But his death would not be in vain. His followers, who called themselves the Hussites, rose up against the Catholic Church. They wanted to take up arms to defend their faith and their right to practice religion in the Slavic language. In 1418, there was a gathering of the Hussites before the great war they would embark on. It is depicted here, in the painting called, “The Gathering at Křížky.”

Koranda

On the right side of the frame, atop a makeshift pulpit stands the preacher Koranda, one of Jan Hus’ most diligent followers. Koranda preaches to the thousands of followers who have concentrated on the hillside. In the foreground, a young man puts his hands around his mouth, in mid-scream. He is calling out for more pilgrims to come over to this spot and listen to Koranda. Koranda is famously quoted as saying, “the faithful should carry swords, not walking sticks.” It was perhaps this moment that the Hussite Wars began. While the painting’s hills and foreground are lit in a pale morning sunrise, there is a dark sky looming above them. This ominous tone is foreshadowing the devastation that will be brought by impending hostilities.

After the Battle of Grunewald

This scene is perhaps one of the most ghastly of all the paintings in the series. The painting depicts the morning “After the Battle of Grunewald“. The great Battle of Grunewald is one of the most significant medieval European victories in history. It was a show of unity for nations under the thumb of Germany. The Teutonic Knights, a German catholic order, had been ravaging the Baltic lands since the 1400s. They wanted to spread Christianity to the pagan nations as they deemed them “savages”. The Slavs, who were also at war with the German Catholics, saw an opportunity to join forces and create a united front against them. The Slavs, the Poles and the Lithuanians all signed a treaty on July 15th, 1410. This was done to help each other defend themselves against the great Teutonic Knights.

Polish–Lithuanian Union

The battle at Grunewald in Poland was a bloody affair, but in the end, the Polish–Lithuanian union were the victors. The battle is thought to have been the marking point in history when the balance of power shifted in Central and Eastern Europe. Many historical war scenes are often depicted as gory and bloody and yet Mucha chose a different approach. Instead, the battleground is almost entirely white, like covered in freshly fallen snow. This is once more to show the purity of the fallen soldiers, who died for the good of their country.

At the top of the frame stands Polish King Władysław Jagiełło and his cousin the Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas. They look down at the field of dead soldiers in horror. Such a high cost for freedom which should have been granted naturally. A priest in a white hood can be seen blessing the fallen soldiers as he moves throughout the battlefield.

After the Battle of Vítkov

The 11th piece in the series is entitled “After the Battle of Vítkov.” Like the previous painting, this one also focuses on fallen soldiers. Mucha was a pacifist and hated the loss of which war incurred. The battle was between the Czech people and the then King of Hungary, Sigismund, brother of King Wenceslas. Sigismund was thought to be the one who plotted the death of the people’s prophet, Jan Hus. After Hus died, the people refused to accept Sigismund as their king and marched against the Hungarian army, which occupied Prague Castle at the time.

Zižka

The sun rising above the clouds beams down on a figure which represents Zižka, the leader of the Czech army. We have seen Zižka before, first in the church scene listening to Hus’ teachings. Here we see him still fighting for the same things Hus had preached. Zižka is painted here by Mucha almost as a saintly figure, with the light of god cast down upon him.

In the bottom left of the frame, a mother is seen with her children. But she turns away from them, towards the viewer. She looks utterly overcome with pain, exhaustion and defeat. Although her army may have won the battle, many men had to die and she is perhaps thinking about her young children, who will no doubt go to war like so many other young men. These powerful characters looking out at the audience always seem to have these discerning looks, as if they, like the viewer, know what is to come next.

Petr of Chelčice

Mucha aimed with his Slav Epic series to ensure he depicted both sides of the story. And in the painting, “Petr of Chelčice ” we see this balance. While the Hussites were an oppressed people, there were also more extreme factions of Hussites who themselves terrorized many people. This extremist group was called the Taborites. In 1420 the Taborites attacked the village of Vodňany. They plundered the town and burned it to the ground. In the distance of the painting, we see a hint of this action as the black smoke fills the air and almost the entire skyline.

The remaining citizens of Vodňany came to a pond away from the city carrying their dead and wounded in the hopes they would be safe here. The dead are wrapped in white sheets and set against a white pure background. Many of Mucha’s war scenes depict not the action of the battles itself but the after-effects of these traumas on the innocent victims or those left behind. Those who needed to carry on.

Petr Chelčický

In the middle of the frame, we can see a man dressed in a long brown coat and pale blue shawl. He holds a tattered book in his hand, the Czech bible. This is Petr Chelčický. Petr is seen holding the hand of a man, who in anger wants to set off back to the village to avenger his fallen family. But Petr is attempting to calm and dissuade him from seeking revenge.

Chelčický believed and taught pacifism and hated the idea of war. Mucha himself shared in this belief and wanted to highlight the man which he himself looked up to greatly. Petr Chelčický would go on to found the Unity of the Brethren. Their motto was “In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, love.”

The Hussite King Jiří z Podĕbrad

Despite the strength and unity of the Czech people, Rome was still in opposition to them. In 1458 Bohemia elected its first king; Jiří z Podĕbrad portrayed here in “The Hussite King Jiří z Podĕbrad“. Jiří z Podĕbrad was well-loved by his people. With many successful battles, the Hussites had demanded an acknowledgement from the Church. Jiří z Podĕbrad sent an envoy to Rome with a treaty. He asked that the Pope confirmed his election and grant Bohemia their own religious privileges. The Pope sent back to Prague his cardinal Fantinus de Valle, to the Royal Court in Prague’s Old Town.

Mucha’s Villains

In Mucha’s series, so many of the villains are seen painted in red. And there is no purer red, than the cardinal’s robes. He is centred in the frame, surrounded by the golden light flowing in through the gothic tracery’s stained glass windows. But instead of the golden light on the sun seeming holy or uplifting, there is an ominous, almost firey tone, to the lighting. He has not brought news of peace but of more war. The profile of Fantinus has actually been modelled off Pope Pius II. Fantinus was mere a solider in the Pope’s envoy.

The scene around him is calamitous. The king is seen turning away, his chair on its side, no doubt having been kicked down in a fit of rage. The overturned chair also represents the fact that Bohemia was still not seen as an official kingdom as the Papacy would not acknowledge it. At the bottom of the scene, in the center of the frame, we see a young boy looking out at the viewer. The boy is holding a book in his hands, which has the words “Roma” written on the cover. The book is closed, depicting the fact that Rome has closed the door on the Bohemian people.

The Defence of Sziget by Nikola Zrinski

“The Defence of Sziget by Nikola Zrinski” stands out, as the red hue is so saturated in juxtaposition to the softer tones of the rest of the series. The scene is fiery, literally. It depicts the last assault of the Bohemian forces against the Turkish army. In 1566, when this painting is set, the Ottoman Empire was spreading eastwards, taking city by city by force. Their next attack was set on the city of Sziget, a town in modern-day Hungary.

Nikola Zrinski

Within the walls of the city, the last remaining Bohemians forces gather around their leader, Croatian nobleman Nikola Zrinski. With no way out, the soldiers and common folk decided that instead of surrendering, they would fight to the very end.

One of the most dramatic moments of the siege is the burning of the city. Upon seeing the Turkish forces burst through the battlements, Zrinski’s wife Eva set fire to the city. She knew while this would no doubt kill hundreds of her own soldiers, but it would also kill thousands of Turks. And perhaps stop their advance into the rest of eastern Europe. In this scene, we can see Eva, along with other fellow women, climbing the scaffolding which contained the cities gunpowder supply. They ready themselves, for the right moment, when the Turkish army is close. Then Eva will hurl down the cresset she holds, to set the entire thing ablaze. You can see Eva at the very top of the scaffolding, standing proud and regal, brave in the face of her sacrifice. It was this decision that successfully halted the Ottoman expansion towards the city of Vienna.

Dividing the canvas like a scar, is a dark plume of smoke rising from the ground. The smoke is so thick it doesn’t seem to belong in the earthy realm. Instead, perhaps it is foreshadowing the demise yet to come. This battle is often referred to as “the battle that saved the civilization.”

The Printing of the Bible of Kralice in Ivančice

“The Printing of the Bible of Kralice in Ivančice” is of particular importance to the Mucha, as it depicts his hometown. The town of Ivančice where Mucha was born is faithfully reinterpreted for us here, on a seemingly idyllic autumnal afternoon. No doubt he would have chosen his favourite time of year to paint this scene. The painting shows members of the Brethren School, gathered in 1578 to admire their new printing press, at work producing the first Czech translation of the New Testament.

Jan the Elder

This theme of all men being equal was something Mucha believed in and was preached by the Brethren School itself. The teacher Jan the Elder of Žerotin can be seen almost obscured under the wooden shelter on the left side of the canvas despite him being one of the founders of the school. In reality, while the Brethren School was located in Ivančice, the bible had to be printed in secret in the town of Kralice. While the action is celebratory, the act of printing the bible in another language was seen as an affront to the Catholic church.

In the foreground of the frame, we see an old man reading to a young scholar. The scholar is looking out at the audience, with a look of apprehension or perhaps impending doom in his eyes. He seems to know that this act is bound to bring persecution down on the school. But printing the bible in Czech was in itself a symbol of the power of the Czech national identity. Since the bible was one of the most-read pieces of literature, having it in your own language ensured its legacy.

Jan Amos Komenský

As foreshadowed by the look of terror in the boy from the previous painting, the religious liberties of the Bohemian people would not last. In 1619 the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II became King of Bohemia. Without a true Czech King on the throne to fight for the rights of the Bohemian people, the Catholic church was reinstated in what was now a Protestant region. But not without bloodshed. In 1620, 30,000 Bohemians died trying to defend their liberty. Noblemen and academics were given the choice to convert to Catholicism or to be exiled.

Naarden

The painting of “Jan Amos Komenský” depicts the result of this exile. Komenský had been a member of the Brethern school who faced this choice. Not wanting to bend the knee to the catholic church, he left the country he loved so much, breaking his heart in the process. He spent the rest of his life in the town of Naarden, in the Netherlands. The town is located near the water, and historically it was said that Komenský would walk along the coast every day. Perhaps the calm sound of waves crashing on land allowing him to dream about the country he left behind. One day, when he felt like his life was coming to a close, he asked for a chair to be brought out to the coast. There he sat, and let death take him home once more.

The scene is painted in a sombre, yet peaceful swath of blues and whites. The purity of the white shores upon which he walked is framed by the melancholy blue of the sky. The sombre sky reflecting the sadness which Komenský felt being compelled to leave his homeland and many of his people. A group of his followers can be seen grieving on the shore, holding each other close. A single lantern sits on the sand, glowing brightly in the darkness, perhaps a hint at the hope which still exists for the Bohemian people.

Czech Mason Temple

This is the only painting in the series which Mucha actually signed! Mucha was deeply connected to Komenský. It is well known that Mucha was a member of the Czech Mason Temple, which was founded in Prague in 1919 and named after Komenský himself. One of the symbols of the Masonic Temple is the Eye of God often seen in a triangle surrounded by rays of light. It is thought that Mucha’s inclusion of the lantern in this scene is symbolic of this same Eye of God and therefore a masonic symbol.

The Holy Mount Athos

The 17th piece in the series is called “The Holy Mount Athos.” Mucha believed that Mount Athos was a spiritual nest for the Czechs and Slav people. Mount Athos is a mountain in northeastern Greece and an important centre of Eastern Orthodox monasticism. Mount Athos is home to 20 monasteries under the direct jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Mucha visited the mountain himself in 1924. The spiritual haven made a huge impression on the painter.

The painting depicts the Russian pilgrimage to this holy site. Once more, we are privy to Mucha’s depiction of the heavenly and the earthly places above and below the canvas. In the upper portion of the painting, we can see the celestial realm. An ethereal glow falls in through the windows, showering the angels in heavenly light. Each of the angles holds in their hand a small model of a Slavic monastery that was built around Mount Athos. Each one of the angels seems to shelter and protect these little treasures. In the center of the frame are two female angels, identifiable by the fact they are not barechested and instead draped with immaculate white fabric. They hold an insignia in their hands which indicates they represent “faith” and “purity”.

High Priests

In the earthly plane, we can see the Russian pilgrims entering the sanctuary in a semi-circle, bowing and praying. Four high priests stand at the back of the scene, just under the Slavic icons. Each one of them holds a relic in their hand which the pilgrims kiss upon greeting. In the foreground of the canvas, we see once more a young man, holding up an older blind man in his arms. One can imagine them to be the same two figures from the school of the Brethren a few paintings ago. The young man, being so inspired by the teaching of the older one, has helped bring him to this holy place where he can finally be at peace.

The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree

There are two important things to understand when reading the painting “The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree”. One is mythological and the other historical. The historical piece of the story is imprinted in the title with the mention of the Omladina. The Omladina were a group of Czech Nationalists made up mainly of youths created in the 1890s. 68 members of the group were furthermore put on trial for their beliefs and sent to prison for their “radical” ideas. These ideas revolved around the creation of a Czech nationalistic revival, despite the fact that Bohemia was currently occupied by the Austria-Hungary empire.

The Daughter of Sláva

The scene which takes place here combines the Omladina with an allegorical scene of the Daughter of Sláva. Mucha was inspired by the poems of Ján Kollár whose oeuvre focused on stories of the gods and goddesses from Slavis history. The Daughter of Sláva stands in the center of the frame, beneath a Linden tree. The Linden tree is also a symbol of the Slavs. Surrounding the tree, in a circle of unity, are imagined members of the Omladina. The Omladina are in the process of taking an oath and pledging their allegiance to the goddess Slavia, and to the Czech people. While the men in the frame are portrayed in their formal, modern-day fashions, there are groups of figures surrounding them dressed in folk costumes. These are traditional representations of the first Czech people.

Jaroslava and Jiří

Sitting on what almost looks like the edge of a stage are two figures, a male and female. These characters were actually modelled off Mucha’s own children; Jaroslava and Jiří. The composition of girl on the right strumming the lyre was actually used in the posters that Mucha created to promote the exhibition of the Slav Epic in Prague in 1928. Mucha would never finish this painting, and the composition remains bare on the canvas, unvarnished. The faces are also unfinished, but in a sense that almost makes the painting more interesting as future Czech revolutionaries can imagine their own faces in the image. Inspiring them to never lose their Czech identity and the histories that come along with it.

The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia

Mucha’s painting of the “Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” is a real reflection of the artist’s disheartening experience of visiting Russia for the first time. Mucha had always looked up to the Russians and was excited to finally visit the city. But when he got there in 1913 he was so disappointed to find the city was overrun with poverty and suffering. It was not the progressive place he thought it would be, instead, he found so many cultural practices to be years behind the rest of Europe. Especially in terms of equality, something he valued over everything else.

Tsar Alexander II

Tsar Alexander II had given Russian serfs personal freedom in 1861. Which Mucha felt was long overdue. The term “serf”, referred to an unfree peasant of the Russian Empire. They differed from slaves only in the sense that they could not be bought and sold independently from their land. Instead were “attached” to the land they lived on. So if you bought a piece of land, the serfs came with it, but could never be moved from that spot. The emancipation movement of 1861 meant that 23 million people received their liberty. They now could marry without having to gain consent, could own property and even start a business.

When the edict was read out, as portrayed here, the serfs and nobles alike had much uncertainty about what this freedom would look like. For the peasants, having never known this kind of life before, some of them were overwhelmed and confused. Mucha’s crowd is subdued rather than excited. They sit for a moment, apprehensive that the emancipation order could be being revoked. And this liberty taken away as fast as it was given.

St Basil’s Cathedral and the Kremlin

St Basil’s Cathedral and the Kremlin are almost completely obscured in the background of the scene by the thick fog. Making the picture more about the people than the country which looms over them. The sun is only starting to peek out of the clouds, offering a faint glimmer of hope. In the foreground of the picture, once more we see a mother and child looking out at the viewer. Their faces are a complex mixture of trepidation, anxiety and optimism.

The Apotheosis of the Slavs, Slavs for Humanity

The final painting in the series is perhaps the most impressive, the colours within its frame is almost otherworldly. It’s entitled “The Apotheosis of the Slavs, Slavs for Humanity.” In this scene, Mucha sums ups all the themes that were explored throughout the preceding paintings.

It celebrates the independence of the Slav nation in the 20th century.

The painting is divided into four sections, each separated by colour. The blue portion in the bottom right represents the mythology of the Slavic people. Those stories are the bedrock upon which their culture was built.

The red in the top-right reflects the brutal Hussites wars fought in the middle ages. The dark shadowy figures on either side of the painting represent the enemies of the Slavic people and the oppression they surrounded the Slavs with throughout their lifetime.

Independent Czech Republic

The last group is the one marked with a bright yellow glowing light. In the centre, a man stands with his arms outstretched. So vast, they almost touch the edges of the canvas. He represents the new, independent Czech Republic. But he doesn’t stand alone. Behind him is the figure of Jesus Christ, supporting him on the journey to come. The man greets a group of soldiers, seen in their uniforms, returning from the First World War. The Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed after WWI, and the Slavic people were free of their reign in 1918. Just below the waist of the towering figure is a man crouched over, holding his heart. From his clenched hands, a beam of light is radiating. The light represents the Czech people’s love for their nation. And it is this love that will illuminate the future pathway for the Slavic people.

Young boys and girls wave branches with bright green leaves, saluting the men returning home from battle. They are seen wearing traditional folk costumes. Symbolic of the fact that their traditions will never die and will continue in the hearts of future generations.

Souls of the Slav People

Mucha hoped that those who viewed these paintings would be able to see into the souls of the Slav people. He wanted all Slavs and Czechs, now more than ever, to come together through their shared history. He hoped that by documenting these stories, perhaps unknown by many, they would find peace and hope. I had never known anything about the Slavic people until I visited Prague. After experiencing this series I was so inspired to do more reading about the stories portrayed here in the Slav Epic. By understanding the past these people suffered and survived through you have so much more appreciation for the culture they had to fight to preserve.

Fully taking in the Slav Epic can take some time, but the experience is absolutely worth it. I hope that when it finally reopens in its new home in Moravský Krumlov people flock to see it. This is a collection of works of art that NEEDS to be seen in person to be fully appreciated. While learning about it online is great, seeing these gigantic paintings, overtake your field of vision is such an awe-inspiring experience and I truly hope you all manage to see it for yourself!

4 COMMENTS

Larry S. Kendrick

5 years agoAwesome pictures making one appreciate slavic history

laura.f.whelan

5 years ago AUTHORThanks so much Larry!

Craig Bresley

4 years agoI have always been a fan of Mucha. I found out recently that his paintings were on such a grand scale. Thank you for the history and the great photos.

laura.f.whelan

4 years ago AUTHORThanks Craig! He is one of my favourite artists but know people mainly know his more commercial work so I’m so happy people are loving this post as the ‘Slav Epic’ is a true masterpiece.