There are hundreds of museums in Florence, more than anyone person could attempt to see throughout a short vacation. But for those of us interested in the strange and sublime, La Specola Museum is one not to be missed. When I visited Florence, this museum was the #1 thing to do on my trip. That’s right, more important than the Duomo, the Uffizi or the Pitti Palace; was a visit to La Specola.

I have been obsessed with Cabinets of Curiosities ever since I was young. I loved collecting shells on the beach, finding interesting pieces of ephemera and random bits and bobs to display in my mini-museum (aka my bedroom shelves.) Today my curatorial cabinets are filled with more refined historical oddities and memories of my travels.

About La Specola Museum

The Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze is also known as ‘La Specola’ is considered the oldest scientific museum in Europe. It was the first public Cabinet of Curiosities turned museum. But what you’ll find inside isn’t for the faint-hearted. The most infamous items on exhibit here are 18th-century anatomical wax sculptures! If you’re interested in an alternative kind of museum in Florence that features incredible medical history treasures, then this is the place for you! Be warned, this post features many pictures of the anatomical wax models so proceed with caution if that isn’t your thing.

Hours, Access and Admission

Hidden away, behind the walls of the Pitti Palace, is the Museum of Zoology and Natural History which contains the La Specola collection. As with many places in Florence, the best way to get there is on foot. But in case you are coming from further away, both Bus #11 and Bus C4 stop within less than 5-minutes of the museum’s entrance.

Admission: Adults €6.00 | Children €3.00

Hours: Tuesday to Sunday 10:30 am to 2:30 pm Closed Mondays (be sure to check updated schedule changes due to COVID restrictions.)

History of the Museum of Natural History in Florence

The history of the collection dates back to the 18th century with the infamous Florentine family, the Medicis. The House of Medici was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that practically ruled Italy for centuries. The Medicis produced four Popes of the Catholic Church and several highly influential Dukes. There really isn’t anywhere or anything in Florence which doesn’t owe a part of its history to the Medici’s. The family had a great passion for art. Through their patronage, many icons of the Renaissance were created. But in addition to art, they were passionate collectors. Their collections included fossils, animals, minerals, exotic plants and medical curiosities, including wax anatomical models.

Cabinets of Curiosity

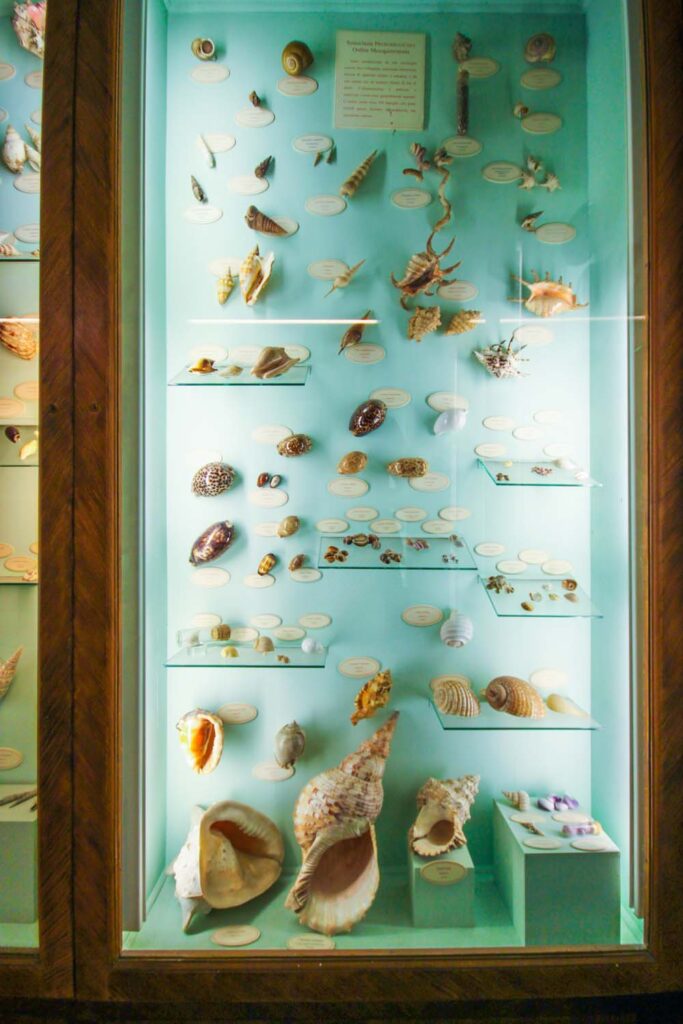

These collections of random objects were called ‘Wunderkammer,‘ German for Cabinets of Curiosities. These cabinets contained objects belonging to natural history, geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, works of art and antiquities. The cabinets themselves were often enormous. Beautiful gilded wooden creations. They were often embellished with mother of pearl inlays, elaborate paintings and gilded mirrors. The mirrors which served as backdrops to the cabinet made even the smallest collection look much larger.

High Society Entertainment

Cabinets of Curiosity emerged in the sixteenth century. They were mainly found inside homes of wealthy rulers, aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science. Aside from the scientists, the private collections didn’t really reflect the passions or interests of the owners. Instead, the contents were meant to impress and entertain guests. If you had a very rare item, your guests would be amazed. Back then, long before Netflix or cable TV, the way you could travel around the world while still at home was by viewing these awe-inspiring cabinets. The more items you had and the more unusual they were, the better it reflected your high rank in society. Only the rich were able to possess such treasures.

Gentlemen’s Clubs were also popular places to find rich Cabinets of Curiosities. Different members of the group would bring in additional items to add to their outstanding group collection. During large meetings, the discussion around newly added items would be the talk of the town!

Museo di Fisica e Storia Naturale

In 1771 Grand Duke Peter Leopold founded the Imperial Regio Museo di Fisica e Storia Naturale. This would be the Imperial-Royal Museum for Physics and Natural History which was eventually nicknamed, “La Specola.” “Specola” is the Italian word for observatory, a reference to the astronomical observatory founded here in 1790.

Many of the items he acquired for this museum were either on loan from the Medicis or gifts to the Grand Duke. When it opened in 1775, it was the first Cabinet of Curiosity open to the public. Many of the lower classes would never have seen something like this before. And seeing these collections in person would have been a wildly exciting event. Many Royal societies viewed the museum as a means of promoting knowledge of the natural world. And spreading that knowledge outside of just the academic classrooms and into the public.

Guide to the Museum

Hidden away along the Via Romana is a large, stone archway with two huge wooden doors. Aside from a small hanging poster on the side and the words “Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze” above the entrance, you’d hardly give this place a second look. But this is indeed where you can head inside to discover the treasure within. Passing through the same gateway people have walking through for over 250 years.

Mineralogical Rooms

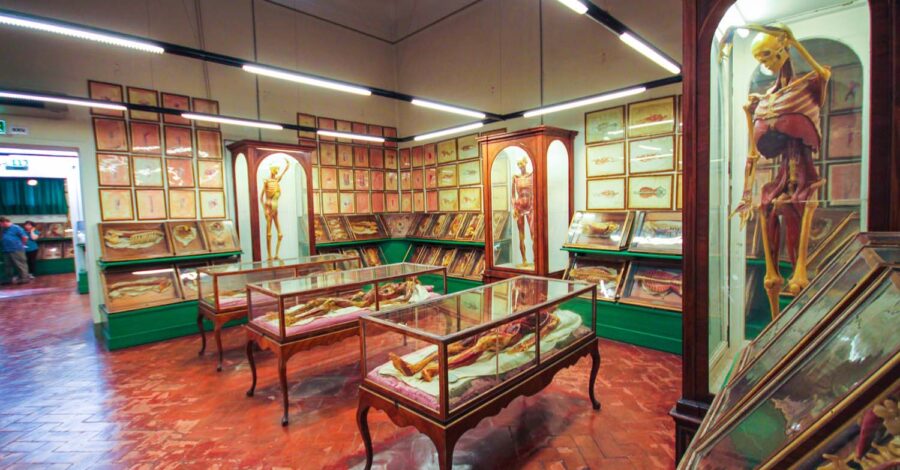

The museum contains 34 separate small rooms spread out around the building. Inside each, you can discover an array of different specimens. The first room you can explore is the mineralogical room. Here, the University of Florence offers a glimpse into the world of minerals and rocks. There are over 50,000 specimens from all over the world, including meteorites!

Zoology

The next set of rooms contains the Zoology collection. There are three and a half million specimens in the group, but only 5000 are on view to the public. The rest are in storage. All of the animals on display are stored inside large glass cases along the walls. Everything from invertebrates to more evolved mammals can be found here.

The mollusk collection even includes mother-of-pearl objects taken from the Medici collection. The Specola collection of birds features winged creatures from all over the world. They even showcase extinct breeds from the 18th to the 20th century. Their gorgeous brightly coloured feathers looking more like art objects inside those glass cases.

The reptile room features giant turtles from the Galápagos and even a mummified crocodile from Ancient Egypt. One of the most famous pieces in the collection is a stuffed hippopotamus! The hippo was once a Medici family pet who lived inside the nearby Boboli Gardens.

Conte di Torino

The Conte di Torino hall is where you’ll find a collection of the Royal Family’s hunting trophies. Rhinos, antelopes, baboons, a tooth of a narwhal, and an arctic cetacean are all parts of this collection. Bringing these unique creatures back from far away lands was another way that rich families were able to show off their wealth and access to guests visiting their homes.

Hall of Skeletons

The Hall of Skeletons is open only on special occasions or with a guided tour by appointment. So it’s definitely worth asking when entering the museum if the room will be open or if a guided tour is available. Inside this large room are the skeletons of numerous animal species. The most iconic of which is the reconstruction of a huge humpback whale hung from the ceiling. In the centre of the room are the bones of several small elephants. Lining the glass cases on either side of the room are more birds, fish, reptiles and mammal skeletons. This includes several monkeys and even a few human skeletons.

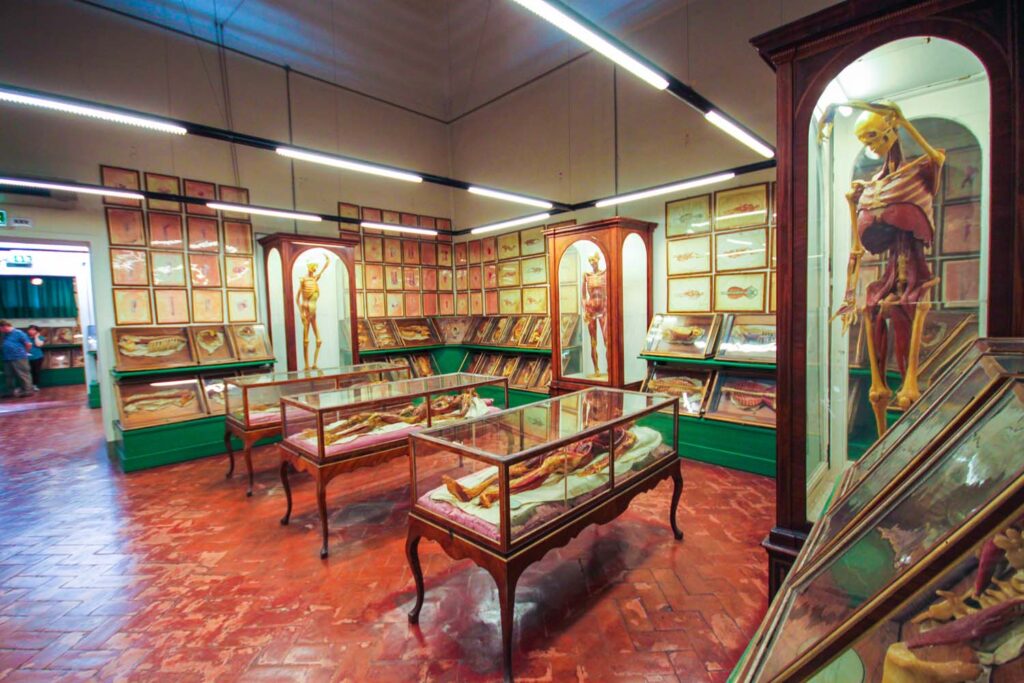

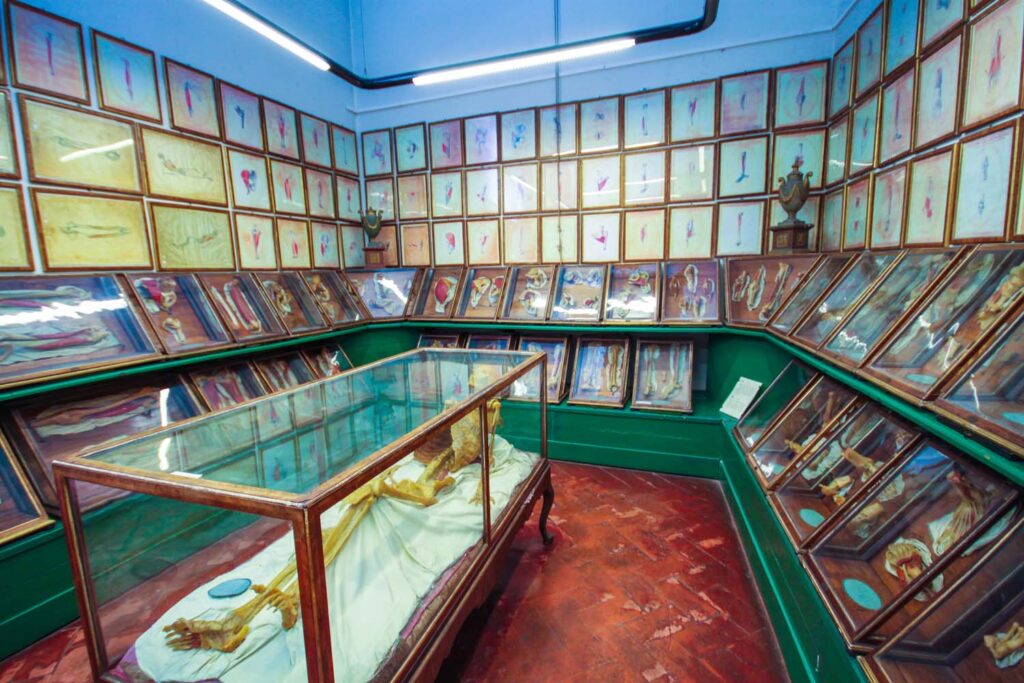

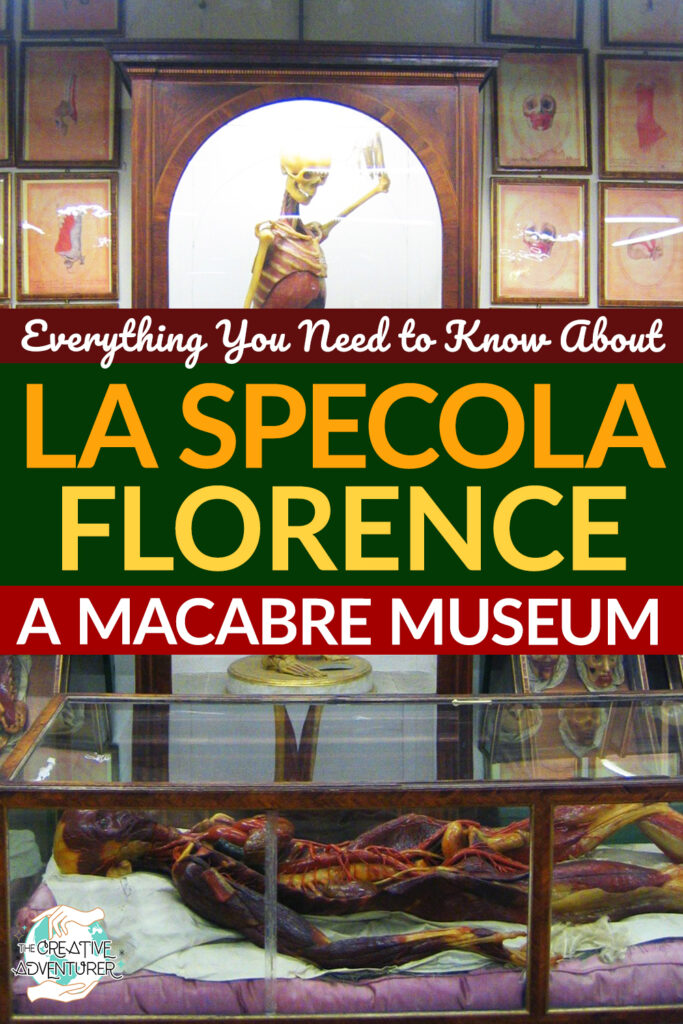

The Specola Anatomical Waxes

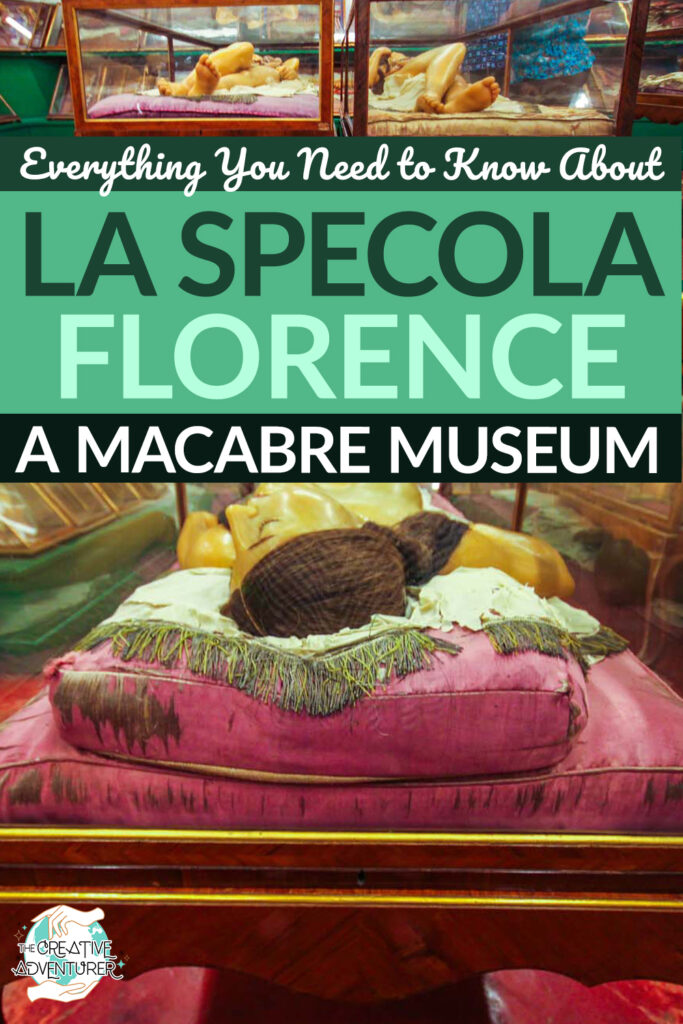

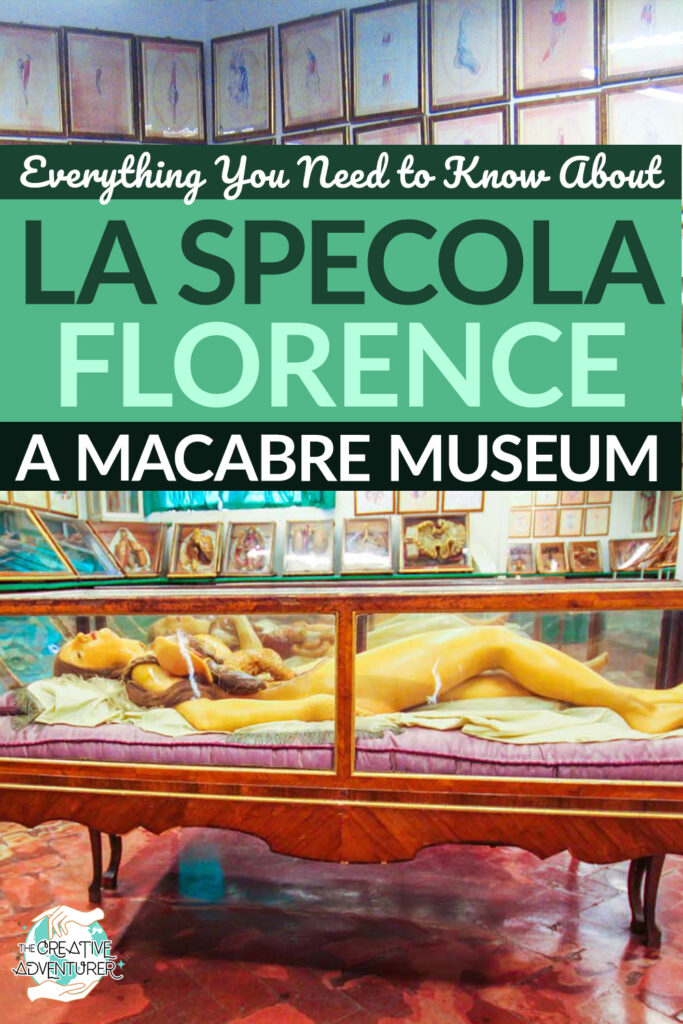

But the real reason that people come to visit La Specola is to see the Anatomical Historical Waxes. The museum in Florence is home to the most extensive collections of anatomical with over 513 wax models on display. Twenty-six of these specimens are full life-size figures. The rest of the smaller sculptures are of one particular area of the body, shown in full anatomical detail. Each of the life-size models is housed inside a beautiful wooden framed glass case. The walls around the exhibition space have beautiful framed watercolour and pencil drawings. These were used before the modellers before working to create the incredibly lifelife wax models.

History of Anatomical Waxes

In the 16th century, during the height of the Renaissance, both artists, scientists and physicians began in-depth studies of the human body. Artists used these studies to refine the realism of the body in their paintings. Physicians aimed to discover a myriad of different secrets hidden within the human body. Until now, the Catholic church had banned the dissection of the human body. The church viewed dissection as sacrilegious. Because of this doctors didn’t have the chance to understand even the structure and physiology of the human body. But during the Renaissance, these bans were lifted, and the dissection of cadavers for science and art began.

While corpses were helpful, they were also temporary. There was no modern temperature control to keep bodies from decomposing rapidly. In addition to this, the supply of corpses was slow and unpredictable. Most people during this time didn’t want their bodies donated to science. Many people still viewed this kind of dissection as an affront to their dignity. As a result, some doctors even turned to grave robbing to aquired bodies to dissect.

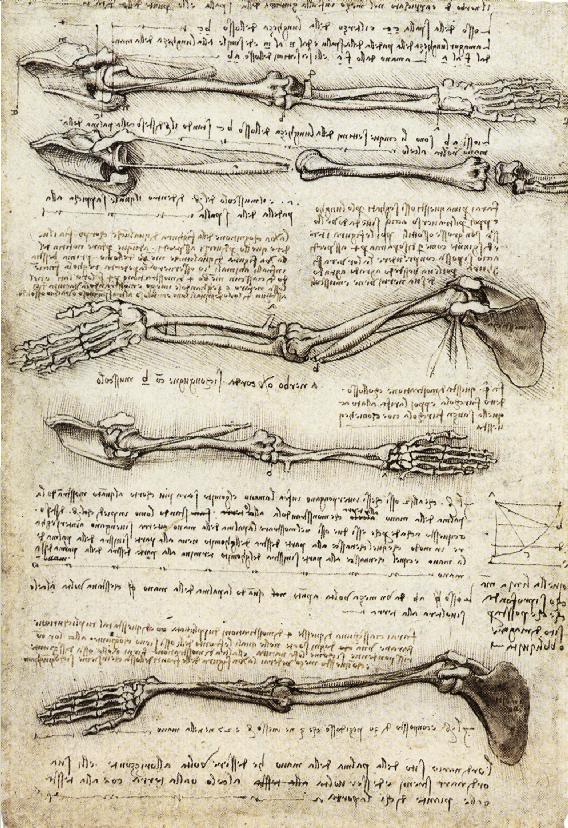

Leonardo da Vinci

Inspired by Michelangelo‘s use of wax to make minature models, Leonardo da Vinci started to create his own wax studies of the human anatomy. Even before dissection was legal for doctors, Leonardo was permitted, by Papal decree, to dissect human corpses. This was performed at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence and later at hospitals in Milan and Rome. His 240 detailed drawings were some of the first images of the human skeleton, musculature and ligaments ever published—a revelation to all doctors and physicians.

But Leonardo wasn’t finished with mere drawings. He began creating models of the cerebral ventricles using melted wax. Leonardo even went so far as to constructed a glass aorta to observe the circulation of blood through the aortic valve.

Wax Workshop

With this new revelation of using wax to model the most minute details of the human body, the art of modelling wax became a widespread practice throughout Europe. By creating these wax models, doctors could study the body for whatever amount of time they required without worrying about acquiring any actual human corpse. And it was right here in Florence where the capital of wax plastic workshops was located.

In 1771, the Grand Duke Leopold of Tuscany opened the wax workshop as a part of the Natural History Museum. Here wax modellers would make the lifeline sculptures, and physicians would gather to teach anatomy to students. The wax models were created as a kind of three-dimensional atlas to the human body.

Material Required for the Models

The models were made primarily of beeswax. Beeswax was the best material to use as it has a slightly translucent appearance, just like human flesh. Dyes were added to give the appearance of flesh, blood and tissue. Because the models are made of literal wax, the temperature inside La Specola is highly monitored. Any spike in the temperature could result in the models melting. Let’s hope they have a good generator in case of a summer power outage!

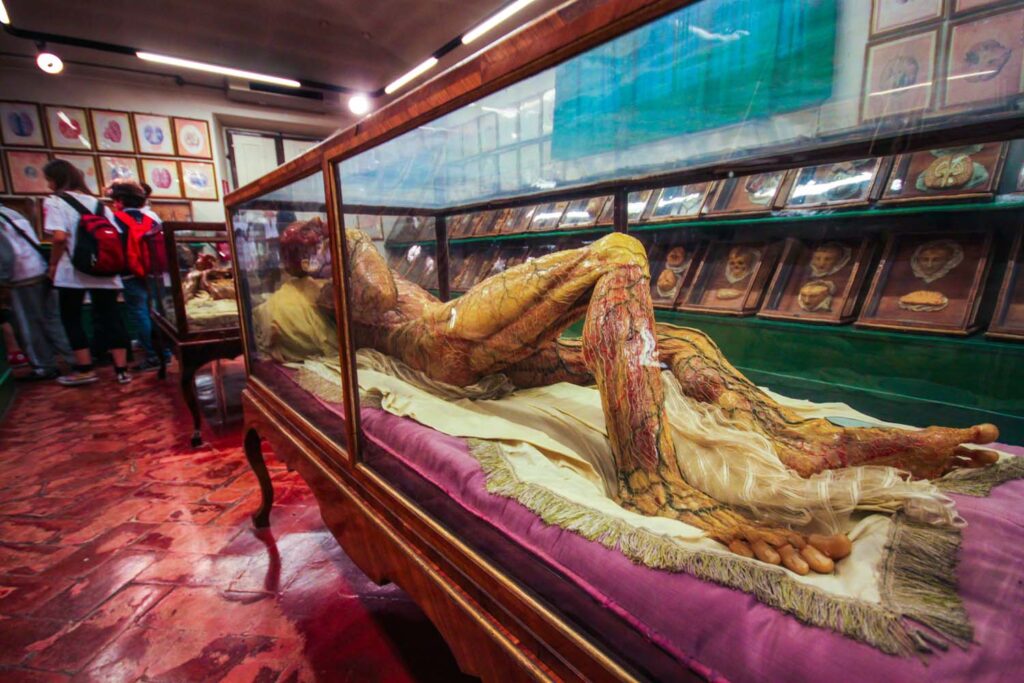

Clemente Michelangelo Susini

The most famous of all wax-modellers was Clemente Michelangelo Susini. Unlike other modellers, Susini’s models were not only realistic but beautiful. Like living works of art. The models postured into artful poses. As if plucked from a Renaissance painting. Many praised him for “the beauty which he gave to the most revolting things.” He began by creating male sculptures. He based these works on postures and sculptures by Michelangelo. They stand or recline tall and proud, despite their flesh being peeled away, revealing the veins and muscles below the skin.

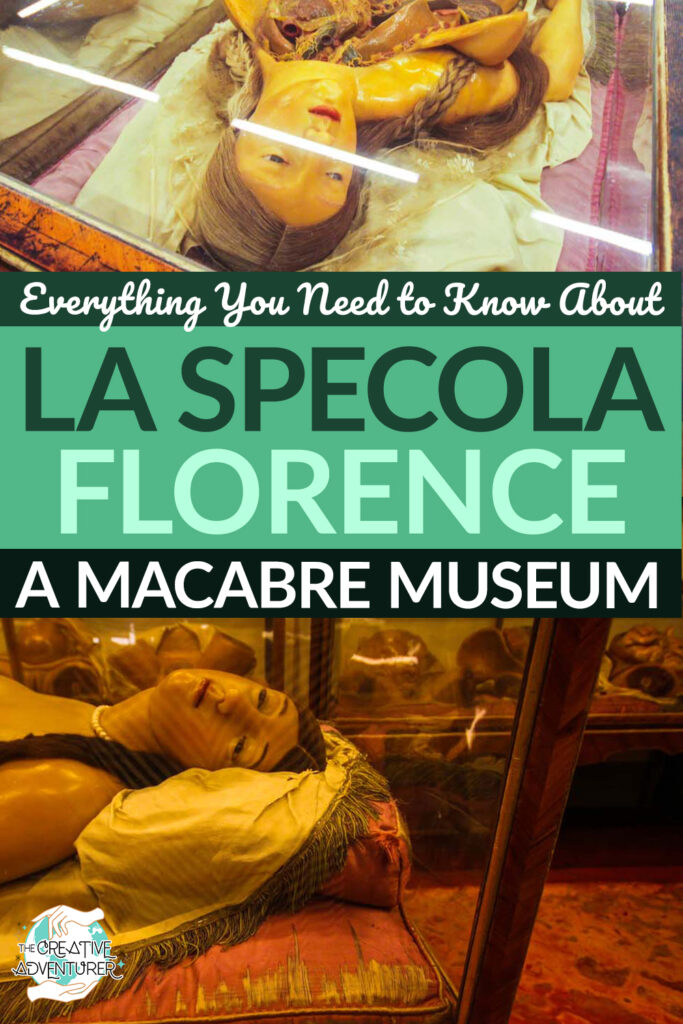

The Anatomical Venus

One of the most popular forms of wax models was that of the female anatomy for use in obstetrics. Women were dying of childbirth at an alarming rate. The thought was that if they could understand more about the internal functions during pregnancy and the process of birth, they could help prevent many deaths. And they were right! These female models had removable cavities that would reveal internal organs. Their stomach could be peeled back to reveal the fetus inside the pregnant mother. Midwives would use them to study more about problematic pregnancies. This gave them the opportunity to work through ways in which to save both the mother and the child.

The Birth of Venus

Susini’s female models began to be known as Susini’s Vénus Anatomique or Anatomical Venus. Just as Boticelli painted the beauty of the goddess in this Birth of Venus, Susini used wax to bring this otherworldly vision to life. They were thought to be more artistic masterpieces than medical specimens. Their faces were utter perfection, flushed, with lipstick and vivid gaze. Susini was inspired by the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. He took much inspiration from that sculpture and gave Mary’s impassionated appearance to all his model’s expressions.

The idea of seeing beauty in the grotesque was something only done in the Italian workshops. Most other countries weren’t interested in creating works of art. Instead, models produced in the UK, Germany and the Netherlands appeared more lifeless and clinical. But that is what makes the specimens inside La Specola so precious and unique.

“Gentleman’s Collectables”

The position of their bodies was almost sensual. Reclined, their legs gently bent, as if calling you towards them. Despite most of the women being used to display pregnancies, their bodies don’t look pregnant at all. Instead, they were designed to look like a “man’s ideal beauty.” Looking into their crystal clear eyes, you’ll see coloured irises looking back at you. As lifelike as your own. Their lips were slightly pursed. Their hair and eyelashes on their forms were both taken from human donations.

The women’s glass cages are complete with lush velvet cushions and mattresses. Their waxy bodies are propped up with pillows derated with silver and gold tassels. Not a penny was spared to ensure their comfort, giving more credence to the lifelike nature of these beings.

With the advent of more advanced photographic technologies, the use of wax models in academic settings began to decline. Schools began to sell off their models after they were no longer of use as scientific teaching instruments. Museums like La Specola held onto them for historical purposes. But the Anatomical Venus began to see another life as darkly erotic “gentleman’s collectables.”

Memento mori

In addition to the lifelike wax models, the museum is home to three minature wax compositions. These were made by Italian artist Gaetano Giulio Zumbo. These wax models were commissioned by Grand Duke Cosimo III de ‘Medici between 1691 and 1694. These sculptures were meant to be grotesque representations of the macabre. During this period of the seventeenth century, the aristocrats were obsessed with these kinds of frightening scenes. Memento mori (Latin for ‘remember that you have to die‘) was a popular trend at the time. It was an artistic or symbolic reminder of the inevitability of death. A reminder to people to live fully while you have the change. These works of art in the memento mori oeuvres are invitations to reflect on the transience of earthly existence.

The Waxes of the Plague

The diorama on exhibit here depicts a grisly scene during the epidemic of the plague. Green rotting corpses are strewn on top of the other in the street. As if simply discarded. The plague epidemic took lives without rhyme or reason. The elderly lie on the road, along with the young and even children. A lone living creature is seen in the corner of the scene, holding the body of a fallen comrade. His face crying out in horror and despair.

The scene looks more like a portrait of war than a disease. These creations were often dramatized for a more intense emotional effect upon looking at them. Zumbo also created wax depictions of the spread of syphilis, the corruption of bodies and the Triumph of time. While we would never think to put works of art this dark on display in our home, back in the 17th century, this was the kind of thing that was commonplace to see. Both in art and in real life!

If you find yourself in Florence and are looking for a unique place that will leave a real impact, you must check out La Specola Museum! While the macabre nature of these wax models might not be for everyone, for those interested in the history of medicine, art, and the beauty that can exist side-by-side death, this is the place for you.

Happy Travels, Adventurers!

end

1 COMMENT

Lawrence Manning

2 years agoAre photos allowed in La Specola?

Thank you